By Holly Yan | CNN

In 1976, gunmen stormed a school bus carrying 26 children – ages 5 to 14 – and their bus driver in Chowchilla, California. As part of a ransom plot, they drove the hostages into a rock quarry and forced them into what could have become a mass grave: a moving van soon to be covered with 6 feet of dirt.

Almost 50 years on, those students have become unwitting pioneers in what child trauma can look like decades later. Now, the new CNN Film, “Chowchilla,” delves into how the largest mass kidnapping in US history became a catalyst for change.

There’s the 14-year-old hero who devised a cunning escape to free the hostages – but didn’t get due credit and spiraled down a dark chasm of substance abuse.

There’s the 10-year-old girl who comforted other terrified kids, then spent decades confronting the kidnappers at parole hearings until the agony became too much to bear.

And there’s the 6-year-old boy who fought relentless nightmares and all-encompassing anger before finding unexpected peace.

‘Like an animal being taken to slaughter’

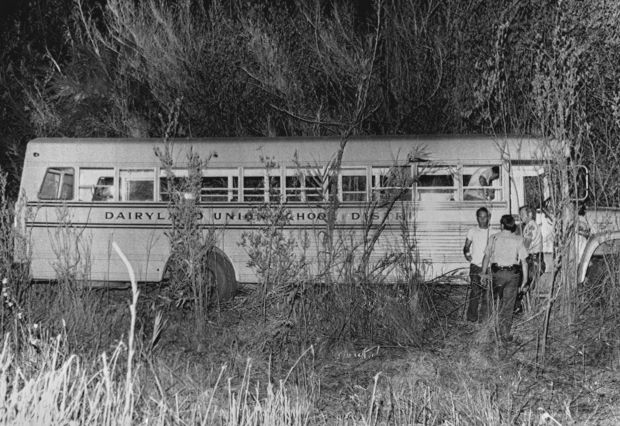

On July 15, 1976, summer school students were headed home from the Dairyland School when a van parked in the middle of a narrow road blocked their driver. A trio of gunmen – pantyhose over their heads – emerged and hijacked the bus.

The gunmen drove it through a thicket of tall bamboo until they reached a ditch hiding two vans.

They ordered the children to get in. Then, for 11 hours, they drove.

“It was just stifling,” said Larry Park, who was 6 at the time.

The kids had no bathroom or water. Some whimpered and cried.

“I remember (10-year-old) Jodi Heffington was one of the older girls who tried to keep the younger kids calm somewhat,” recalled Jennifer Brown Hyde, who was 9 at the time.

“I just felt like an animal being taken to slaughter,” she said.

Their convoluted, unnecessarily lengthy route ended after nightfall at a rock and gravel quarry near Livermore, about 100 miles northwest of Chowchilla. The kidnappers ordered the children and their bus driver into a moving van hidden underground.

“It was like a coffin,” Lynda Carrejo Labendeira, who was 10 at the time, told CNN in 2015. “It was like a giant coffin for all of us.”

The dark chamber – outfitted with some mattresses and meager snacks – quickly filled with the stench of vomit and filth, intensified by the searing California heat.

A daring plan takes shape

The lone adult trapped underground, bus driver Edward Ray, was reluctant to try to escape, “fearful that somebody was up there just waiting,” Brown Hyde recalled.

But Michael Marshall, who was 14, was willing to take the chance.

“I thought to myself: If we’re going to die, we’re going to die getting the hell out of here,” he recalled in “Chowchilla.”

It seemed the only way out might be through a sealed manhole at the top of the entombed van. Marshall climbed onto mattresses the hostages had stacked under it and pushed with all his might.

It barely budged.

Ray joined him, and eventually they pushed the cover open – only to watch two massive truck or bus batteries that had covered it plummet into the underground cell. Then they discovered another sick challenge: a large, reinforced plywood box surrounding the manhole, with more dirt on top.

Undaunted, Marshall pounded the dirt sealing the bottom edges of the box. He dug and dug and dug – until a cascade of dirt fell into the box, through the manhole and into the coffin, revealing “the most glorious ray of sunlight that I had ever seen,” Park recalled.

After 16 hours in the subterranean hell, the 27 hostages climbed their way to freedom.

But the effects of the kidnapping would soon plague the children in myriad ways.

A young hero ‘robbed’

Just freed, the kids went to officially report their ordeal to police. Nearby, news crews gathered. As Marshall walked past them on his way home, a broad grin eclipsed his exhaustion. He had a chance to tell the world how the escape had unfolded.

“Then out of nowhere, Principal (LeRoy) Tatum stepped in and said, ‘Why don’t we just give them a break, boys. Let them go home, get some sleep,’” Marshall recalled. “And so we got in the car and left.”

The diversion would haunt Marshall for decades.

“It was my chance to tell the world what happened – getting out and everything,” he said. “And I didn’t do it; I let the grown-ups do it.”

People across the country quickly assumed Ray was the hero, and lavish praise for the humble bus driver followed. One reporter declared the children had been saved “due to the heroic efforts of their bus driver, Ed Ray.” Chowchilla hosted a parade on “Ed Ray Day” on August 22, 1976. The city named a park after him.

“But Edward was not the only hero,” Brown Hyde said.

Park was more blunt: “I was telling people, ‘Mike Marshall dug us out. It was Mike that dug us out.’ But nobody was listening.”

Photos of Marshall during “Ed Ray Day” festivities show a forlorn young teenager, one his mother could “see was really depressed.”

Even Marshall “felt guilty for feeling bad,” he said. “I remember thinking to myself, ‘Why am I feeling like this? What’s wrong with me?’” He tried to pivot to thinking: “Hey, you know what? Who cares? We all got out. We’re all out, that’s what matters.”

But it cost his mental health.

“Some of that pride from having been the kids’ hero had been robbed from him by the town’s response; he was never acknowledged,” said Dr. Lenore C. Terr, a child and adolescent psychiatry specialist and author of “Children of Chowchilla: A Study of Psychic Trauma.”

Marshall’s fortitude and optimism devolved to hopelessness.

“Before the kidnapping, I could see so much light ahead of me – see my future,” he said. “But then after the kidnapping, I couldn’t see anything.”

By 19 or 20, Marshall was “blackout drunk every single night. I just didn’t want to remember any more about the kidnapping,” he said. “I was drinking and using and all of that to the point where … I was living in insanity.”

‘I wanted to torture those men’

The horror also took a profound toll on Park. His older sister and “best friend” Andrea, 8, had also been kidnapped – and comforted him through the ordeal. But soon after their escape, “I hated going to sleep because every night, I was having nightmares,” he recalled in CNN Films’ “Chowchilla.”

“Mom and Dad were told not to come in when we have nightmares,” he said, recalling experts’ advice at the time to stop “rewarding our behavior of having the nightmares” so the dreams in turn would stop.

But it didn’t work. And soon, Park’s best friend became a distant stranger.

“Andrea became very introverted, where she had been outgoing before. She preferred to hide in her room. She wouldn’t hug me. I would tell her that I loved her, and she would just ignore it like it was never said,” the little brother recalled.

“Over the years, there was an anger building in me that infested absolutely every aspect of my life,” he said. “I was replaying the kidnapping constantly. I wanted to torture those men.”

Stunning revelations about the kidnappers

Authorities said the trio of abductors had tried to land $5 million in ransom as part of the botched kidnapping scheme. When their identities were revealed, Chowchilla residents were flabbergasted.

Frederick Newhall Woods IV, 24 at the time, was from a family that gained prominence during the California Gold Rush. The other two convicted kidnappers, James Schoenfeld, then 24, and his brother Richard Schoenfeld, then 22, were the sons of a well-known doctor.

Each kidnapper soon was sentenced to life in prison without the possibility of parole – a relief to many of the children who’d been taken. But then in the early 1980s, they successfully appealed the sentences based on an argument the kidnapping victims did not suffer serious physical harm, according to the film.

They won: Parole was now an option for all three.

“I couldn’t believe it,” said Terr, a pioneer in the research of long-term childhood trauma. “The mind and the brain – that’s not bodily harm, what you do to a person’s mind? What you do to a young child’s developing mind?”

For Park, the self-loathing and thirst for revenge against his kidnappers became overwhelming. “I was in a prison of my own making,” he said.

“It was one thing that (the kidnappers) hurt me. But they completely shattered my family. Andrea had disassociated from the family and left Chowchilla. My mom lost faith in my dad as a protector.

“I was surviving day-to-day, hated my life, hated myself and hated everyone around me.”

‘I’ve been my own victim’

News that the kidnappers might one day be released horrified many survivors. Over the next 30 years, Jodi Heffington Medrano – the big-sister figure on the bus – traveled to virtually every parole hearing to try to ensure they stayed behind bars.

But each hearing reopened painful wounds for Heffington Medrano, her son Matthew Medrano recalled in “Chowchilla.”

“My mom talked about how she didn’t feel safe around men, her depression, her struggle with addiction issues,” he said.

Park, meanwhile, was searching for a way out of his fury. “I decided to pray,” he explained. “I said, ‘God forgive them, because I can’t. God bless them, because I can’t.’”

He also participated in what’s known as the restorative justice process, which helps crime victims speak with their perpetrators to try to gain closure.

“So I got to go in, and I said, ‘I was your victim for 36 hours. And for the last 38 years, I’ve been my own victim.’ I told them that I forgave them,” Park said. “But forgiving them wasn’t enough. I had spent my lifetime hating them. And so I asked for their forgiveness.”

Park then began speaking out in support of parole – a stance many other survivors vehemently opposed.

‘It’s all my fault they’re getting out’

The kidnappers were repeatedly denied parole until the 2010s, when supporters of their release – including retired judge William Newsom, the father of California’s current governor – publicly advocated for the kidnappers’ parole.

“Nobody was physically injured – huge factor in the case,” the elder Newsom said at a news conference, according to the documentary.

A former detective who’d helped in the prosecution of the kidnappers also later spoke out in favor of their release. “He was one of the people who assured us they would never get out,” Carrejo Labendeira said.

But they did.

In 2012, Richard Schoenfeld, the youngest kidnapper, was released on parole.

Three years later, James Schoenfeld was also released on parole.

“Jodi went into a huge depression,” Carrejo Labendeira recalled. She would say, “‘Lynda, it’s all my fault. It’s all my fault they’re getting out.’”

Soon afterward, Heffington Medrano “couldn’t get out of bed no more. She was so weak because she was just drinking so much,” her son said, sobbing. “She wouldn’t eat because she was so depressed. And she basically just couldn’t process life the way she was supposed to.

“My mom did her best for as long as she could.”

Heffington Medrano died in 2021 at age 55. Her cause of death was not publicly released. But “it was their f*cking fault,” her son asserted.

A year later, the final kidnapper, Fred Woods, was also released on parole. He now regrets the emotional and physical harm caused by the kidnapping, his attorney Dominique Banos told CNN.

“Mr. Woods is truly sorry and remorseful for the mental and physical suffering experienced by the victims because of what they endured,” wrote Banos, who started representing Woods in 2017.

An attorney who represented the Schoenfeld brothers has told CNN, “There’s no justifying this crime, obviously.” But after decades in prison, he said, the kidnappers no longer posed a danger to society.

‘You don’t give up. You keep digging’

Decades later, Marshall is starting to be recognized for his valor – a change that’s boosted him immeasurably, he said. He and Park recently reunited for the first time since 1977.

The two men embraced, and Park called Marshall his “hero.”

“I didn’t realize how much it would help me to understand and to actually hear one of the kids tell me that I saved their lives and that they were grateful,” Marshall said. “Not very many people can relate.”

As a group, the kidnapping victims have been instrumental in teaching the public that childhood trauma doesn’t just cause physical harm – and can fester beyond imagination, Terr said.

“Chowchilla children are heroes,” she said in the CNN Film. “And they continue to teach us what childhood trauma is 46, 47, 48, 50 years after the fact.”

In the end, Park said, Marshall’s courage and strength in those dark hours played an enormous role in helping him persevere after decades of trauma, depression and self-hatred.

“I never gave up – not completely,” he said, “because I was taught, at 6 years old by a 14-year-old boy: You don’t give up. You keep digging.”

The-CNN-Wire

™ & © 2023 Cable News Network, Inc., a Warner Bros. Discovery Company. All rights reserved.