![]()

Nikon, Sony, and Canon will all reportedly bring out support for the Content Authenticity Initiative’s (CAI) C2PA digital signature system in 2024 as the CAI pivots its messaging as a way to combat AI.

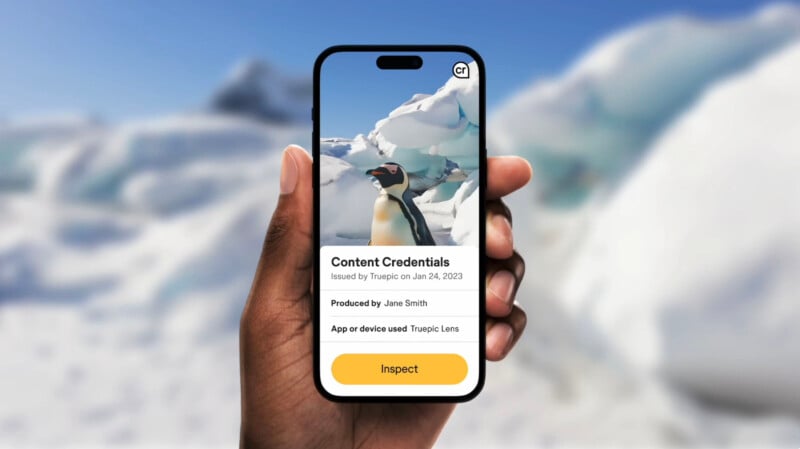

It is becoming more likely that 2024 will see the major camera makers all roll out content authenticity features in some capacity, likely focused on the high-end and professional-level cameras. To this point, only Leica has released a camera that has the CAI’s digital signature system in place but Sony already announced that it would bring the technology to the upcoming a9 III as well as the Alpha 1 and a7S III. That technology passed a test that the company worked on with the Associated Press.

Canon has not made any official announcements regarding the exact camera models that will be supported, but Nikkei Asia reports that Canon will release a new camera with these features as early as this year. Many assume this will be the highly rumored R1.

Canon and Sony are also apparently working independently on a way to add digital signatures to video, although neither has confirmed this.

In addition to supporting the CAI’s Verify system, a web application that is able to show the provenance of an image if it has been embedded with the correct digital signature, Canon is also reportedly building an image management application that can tell whether images were actually taken by humans or if they were made with AI.

Canon was reached for comment but did not provide further details on its plans ahead of publication.

Nikon recently announced that it is planning on integrating an image provenance function into its Z9 camera which includes the Content Credentials system developed by the CAI.

“While currently in development, this function supports confirmation of the authenticity of images by attaching information to include their sources and provenances. The function specially implemented in the Z9 employs a new hash value recording method (General Boxes Hash assertion) added in the C2PA Specifications,” Nikon explains.

C2PA is the name of the standard at the core of the digital signatures that the CAI developed to verify a photo’s provenance.

“Additionally, Nikon has applied this recording method to the Multi-Picture Format (MPF) used in Nikon’s digital cameras, and we are steadily progressing with development to incorporate this function into cameras.”

Of note, the company isn’t stating when to expect these features.

“It is true that we are developing and verifying related technologies, but we have not decided on market launch (release) at this time,” the company tells PetaPixel today.

Fighting AI?

Much of the recent discourse surrounding the CAI and its Verify system relates to fighting the rise of AI-generated imagery. However, despite contextualizing the CAI within current tech trends, this angle significantly misses the point of CAI and arguably promises a future of veracity in imagery that may be impossible.

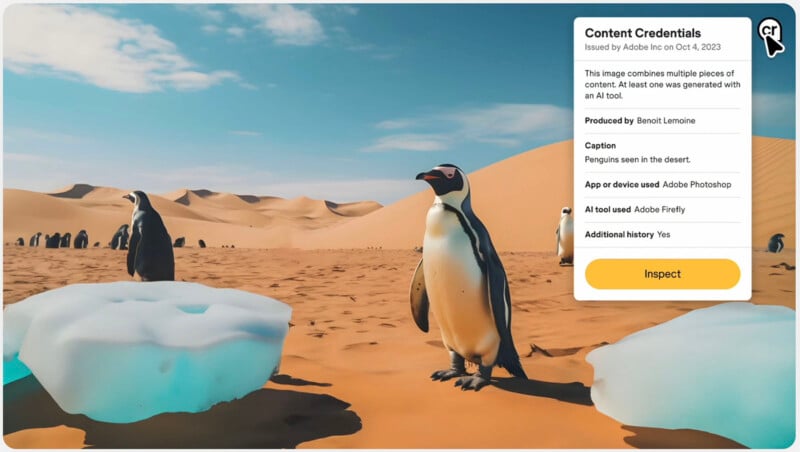

The Verify system is not designed to detect an AI-generated image, although it could at least be able to verify if an image has the CAI’s digital signature attached, which would not be present in a fabricated image. In that sense, it’s not really a system designed to identify fakes as it is one made to recognize and confirm photos that include the CAI’s digital signature.

Given that a majority of photos taken in the world will not have a CAI digital signature and that isn’t going to change for a long time — if ever — to expect it to always identify fake images, whether edited or outright generated using AI, going both forward and back in time in all cases remains an unrealistic goal.

But that hasn’t stopped the CAI itself even from leaning more heavily into an anti-AI stance. The group’s Content Credentials website has been radically overhauled over the last few months (according to data sourced from the Wayback Machine) to emphasize fighting deepfakes and AI.

The original premise behind content authenticity was not to fight AI — the CAI’s initiative and provenance standard predate the proliferation of AI images — but rather as a way for publications to certify that an image has not been altered after it was captured.

When the CAI was originally conceived within the walls of Adobe, the goal was to give media outlets a way to avoid publishing photos that had been “photoshopped” to convey something that didn’t actually happen. That’s still the goal and while it’s true the Verify system would prevent a media outlet from unknowingly publishing an AI image thinking it was real, it’s not the primary objective but rather a happenstance.

That messaging has clearly shifted as AI has become a bigger part of the conversation.

What Does Content Authenticity Mean? What Does it Actually Do?

As recent coverage of the CAI and its reported fight against AI demonstrates, the communication of content authenticity, how it will work, and what it is designed to actually do is widely misunderstood.

The point is that a media outlet like the Associated Press, Reuters, or The New York Times would be able to institute a policy where each would not publish an image unless it had an intact digital signature, therefore protecting them from unwittingly sharing a fake image. That is, in essence, all the CAI and the Verify web app are able to do. Of course, achieving even this goal requires buy-in from camera makers. They have, luckily gotten it and it will start to widely roll out this year.

But the way the system works means images can still be altered and AI image generators can still be used to create renditions of events that might never have happened — those images just wouldn’t qualify for publication in the outlets that are actually checking provenance.

It does not, critically, prevent a fake photo from going viral on social media. That can’t happen without cooperation from social media companies. The biggest issue with misinformation is social media and to this point, none of the major social media players have shown any interest in the CAI’s endeavors. Meta, Twitter, and TikTok are all absent from the list of CAI members.

Without their support, the burden of determining truth falls on the end user.

The CAI envisions a future where all images would have embedded metadata that would allow their provenance to be checked, allowing online viewers to trust what they see as real and even allow creators to maintain credit for their work across platforms.

“Consumer awareness is critical to fight misinformation at scale and we encourage everyone to verify content before trusting it as true,” Andy Parsons, Senior Director of the CAI, told PetaPixel last year.

“The concept is that for important content — such as a viral image or a newsworthy image where someone is trying to prove to you that what they’re saying is true — Content Credentials can provide the context people need in order to make a decision about whether to trust it. Content Credentials empower consumers to verify, and then trust. Important content should have a credential attached. If something doesn’t have a credential, we believe consumers should be skeptical. That’s how we fight misinformation at scale.”

Asking social media users to check the provenance of a “photo” they saw online may be too much to expect out of the average user, but it appears to be the only way right now.

“We envision a new type of ‘digital literacy’ for consumers to habitually check for Content Credentials just like they look for nutrition labels on food,” Parsons added.

The CAI and camera makers like Nikon, Canon, Sony, and Leica can only do so much, and the best place to start is making it so future images do have the C2PA certification. The jury is still out on the billions of photos already available and the billions more that will be made with cameras that lack the built-in CAI support, but what is in the works is the best place to start.

Image credits: Header photo via Sony