As Indira slipped into depression, the maulana was called back. Why had she not summoned him to remove the powerful charm he had placed in her room, he asked her, distraught. She would have to immediately correct the wrong by offering namaz, he warned. Shaken, Indira obliged.

The story, which goes around as a legend in circles of the ulema (Muslim clergy), is related in detail in senior journalist Rasheed Kidwai’s book ‘Leaders, Politicians, Citizens’.

The maulana was Jameel Ilyasi, father of Umer Ahmed Ilyasi, chief imam of the All-India Imam Organisation (AIIO) who made headlines this January for being one of the few Muslim leaders who went for the Ram temple consecration in Ayodhya, and subsequently had a fatwa issued against him for doing so. Ever since the Narendra Modi government came to power in 2014, Ilyasi junior has, in fact, been one of the Muslim leaders frequently in touch with the top BJP-RSS leadership.

“Who do you think gave the land for the organisation’s (AIIO’s) office in such a prime location?” asks senior Congress leader Salman Khurshid, referring to the white-and-green domed structure in New Delhi’s Copernicus Marg. “It was Indira Gandhi.”

The story of the Ilyasi father-son duo underscores the complex relationship India’s mainstream politicians have shared with the ulema over the decades since independence.

Most commentators have sought to understand the relationship through the occasional pronouncements of political fatwas by the ulema — the stereotype etched in the public imagination especially by Delhi Shahi Imam’s famous fatwas prodding Muslims to vote for one political party or the other, especially since the 1980s.

However, in actuality, the story of the ulema’s relationships with politicians and political parties, and their influence on the votes of the diverse and scattered Muslim community of almost 20 crore in India, is far more layered and convoluted than political fatwas would have us believe.

As political scientist Hilal Ahmed argues, “One of the most enduring stereotypes about India’s Muslim community is that their vote is swayed by fatwas and the call of religious ulema in every election.” But it is just that — a stereotype. One, that has been bolstered, election after election, by the myth of a unified “Muslim votebank”, according to which Muslims vote en bloc as a singular community across the country.

The ulema, who have historically aligned with political parties for varying interests of their own — political as well as financial — sectarian rivalries among Muslims, or simply for political patronage, have been seen as the prime movers of this “Muslim votebank”.

But as Muslim politics has changed fundamentally through the 10 years of Modi rule, the role of the ulema is also witnessing a churning of sorts.

Until a few years ago, the ulema were a coveted class of people. Every politician — from prime ministers to chief ministers to local MLAs — wanted to be seen with them before elections. The hope being that the clerics would use their religious influence to put in a word about the party or candidate to their followers.

Now, political parties still want the Muslim clergy to run whisper campaigns for them, but without being seen with them. As Lucknow’s maulana Khalid Rasheed Farangi Mahal says, “Parties still approach us, but don’t want to publicise it; they still want us to campaign for them, but not give us (Muslims) any representation… all for the fear of losing Hindu votes.”

Hindutva has not just pushed the once-visible Muslim clergy behind the scenes, it has also brought to the fore its credibility crisis. Muslims have trusted the ulema for far too long to represent them politically (albeit not electorally). But from the spate of communal riots starting soon after independence, to the demolition of Ayodhya’s Babri Masjid in 1992, to finally losing the title dispute case to the Hindu side after an almost three-decade legal battle — Muslims increasingly feel they have achieved little by posing their faith in their religious leaders.

In the last few years, the three big issues involving the Muslim community — the legal battle for triple talaq in 2017, the agitation against the Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA) in late 2019, and the grand inauguration of the Ram temple this year at the spot where the Babri Masjid stood — have seen the ulema be conspicuous by their absence.

Ten years into the Modi government, India’s once vocal Muslim clergy — seen to be the drivers of the politics of the country’s largest minority — seems to have gone silent.

How did the Indian ulema come to represent India’s Muslims in popular imagination? What were the different facets of this “representation” — did they actually have power to sway the Muslim community’s vote? What are the different ways in which they are viewed by Muslims? And how is their role among the community changing as the BJP-RSS fundamentally overhaul the framework within which politics is enacted in India?

Also Read: ‘Kitney Mussalman hain’: Why this Sachar Committee question to Army was an abomination

The search for ‘nationalist Muslims’

Before the Indian independence, the upper-caste, upper-class Muslims who had embraced modern western education — they largely belonged to what is understood as “the Aligarh Muslim University (AMU) camp” — broadly sided with the Muslim League and the idea of a separate nation for Muslims.

The Congress had to look for another set of elite Muslims who could claim to legitimately represent the Muslim community. For this, they turned to the ulema from the Darul Uloom Deoband seminary in Uttar Pradesh and its Delhi-based associated group, the Jamiat Ulama-i-Hind.

According to Ghazala Wahab, author of Born a Muslim: Some Truths about Islam in India, this served two purposes for the Congress. One, of discrediting the modernists from AMU, and two, of steering the Muslim masses towards the Congress.

The underlying contract between the deeply traditional and revivalist Deobandi ulema and Jamiat Ulama-i-Hind, which had been at the forefront of India’s independence struggle and vociferously opposed the Muslim League’s two-nation theory, and the Congress was this — the former would commit to composite nationalism in a post-independence, secular India, while the latter, in turn, would protect the Muslim community’s religious rights and laws.

While the Jamiat Ulama-i-Hind formally renounced politics, it remained closely associated with the Congress. “It was a relationship of close collaboration,” recalls Khurshid. “We gave several members of the organisation membership of the Rajya Sabha too… this relationship thrived for many decades.”

It was a time when the ulema had considerable credibility of their own. Those who had been at the forefront of the freedom struggle were still around — Maulana Abul Kalam Azad, who was both a member of the Jamiat Ulama-i-Hind and the education minister of the country, is only the most popular mainstream alim (singular for ulema). The ulema’s claim to speak on behalf of Muslims was, therefore, not unfounded.

As Maulana Zahir Siddique, a Lucknow-based alim, says, “The ulema then could scold the community, be affectionate to them — all because they had the legitimacy, scholarly weight and credibility to do so… Muslim masses had seen them closely collaborate with (Mahatma) Gandhi, who Muslims saw as their own leader.”

However, by the 1960s, things began to change.

Various parts of the country witnessed an escalation of deadly anti-Muslim riots — as pointed out by several Muslim activists and leaders, none of these riots were necessarily less bad than the 2002 Gujarat riots. Moreover, the grinding economic marginalisation of the community began to become evident.

The contract between the Congress and the nationalist Muslims was already showing its limits. As pointed out by Laurent Gayer and Christophe Jaffrelot in their book Muslims in Indian Cities: Trajectories of Marginalisation, “Congress Muslims often proved to be men of straw, whose political longevity was conditional to their docility.”

But more tellingly, for some, the odds were stacked up against Muslims right from the formation of the Indian Republic.

“From 1936 to 1950, the category of Scheduled Caste (SC) included Muslims,” says Maulana Aamir Rashadi Madni, president of a local party, Rashtriya Ulama Council. “The (Jawaharlal) Nehru government then added the word ‘Hindu’ to the category of SC, and removed Muslims from it saying there is no untouchability in Islam… we were removed from the development project from the start.”

By the early 1970s, some voices of reform from within Muslims started coming up.

For instance, in 1970, Hamid Dalwai, a Bombay-based journalist and reformer, who historian Ramchandra Guha has described as the “last modernist” in his book Makers of Modern India, started demanding the abolition of triple talaq, and advocated the uniform civil code.

The orthodox Muslims, including the ulema from various sects and schools, who would otherwise not look eye-to-eye, responded by establishing the All India Muslim Personal Law Board (AIMPLB), which would allow no interference whatsoever to Muslim Personal Law. The politics of the ulema’s rigidity had begun.

Muslim ‘votebank’ and political fatwas

By the 1970s, Indian politics had changed considerably. The Congress had already lost the hegemony it enjoyed for the first two decades after independence, and coalition politics, which thrived on the politics of “votebanks” was the order of the day.

The term “votebank”, first used by sociologist M.N. Srinivas in the 1950s, refers to the phenomenon wherein locally powerful people are approached by politicians to mobilise voters of their caste or community. Srinivas had termed these locally powerful individuals as “votebanks”.

In a piece for ThePrint, Hilal Ahmed argues that since the 1960s, non-Congress parties began to mobilise Muslims for making a winnable social coalition of minorities, SCs and backwards. They began to get traction given the spate of riots in the country under Congress watch. The Congress under Indira Gandhi, in turn, began to approach the pro-Congress Muslim clergy as its “votebank”.

Delhi’s Shahi Imam, Abdullah Bukhari, became the face of this politics.

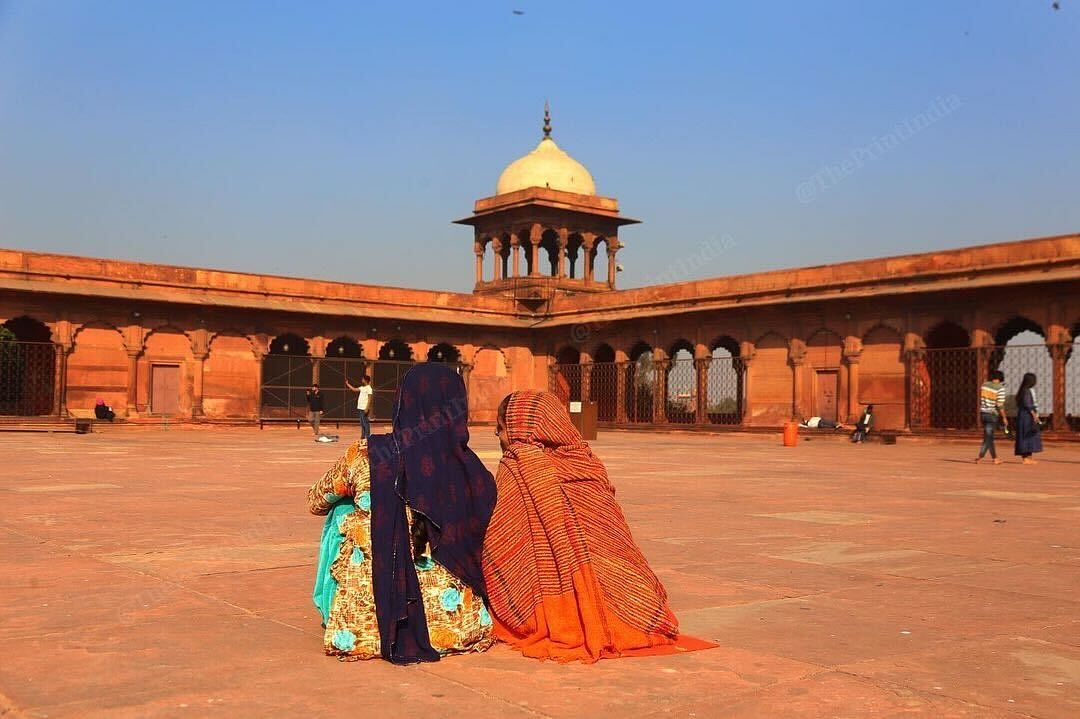

During Mughal ruler Shah Jahan’s time, the imam of the Jama Masjid was designated as the Imam-ul-Sultan (Imam of the Emperor) or the Shahi Imam of the empire, thereby according enormous religious-cultural authority to the mosque. Post-independence, the nostalgia for the Shahi Imam’s past glory continued.

From the 1970s onwards, Bukhari began to regularly give fatwas to the community and campaign for one party or the other.

According to Hilal Hamed’s book Siyasi Muslims, Bukhari was in 1974 first approached by the Congress to support its controversial family planning programme. He obliged by issuing a fatwa in its favour. The same year, he began to oppose Indira Gandhi and was arrested during the Emergency. In 1977, he issued a fatwa in favour of the Janata Party. In 1979, he was again approached by Indira Gandhi through an open letter requesting his support. He agreed, and campaigned for the Congress.

In 1984, he supported (Indira’s son and then PM) Rajiv Gandhi. In 1989, he supported the Janata Dal again. An article in India Today magazine in 1993 says that this was his “real moment of glory”.

“The Janata Dal, led by V.P. Singh, courted him so assiduously and fawningly that it even asked him to vet its list of potential candidates for the Lok Sabha elections,” said the article. By 2004, Bukhari had issued a fatwa in favour of the BJP!

The Shahi Imam’s location in Delhi and his close hobnobbing with politicians created a lasting impression of his importance — but one that is refuted by Muslim scholars, leaders and activists in its entirety.

“Jab Shahi Masjid hi nahi raha, toh shahi imam kahan ke?” a senior Deobandi cleric, who wished to remain anonymous, said. “Unke fatwon ne hi toh humara naam bigada hai.”

Also Read: 5 myths about Muslim voters in modern India

‘Islam in danger’

But it was not just the Shahi Imam. The decade of the 1980s saw a massive churning in Muslim politics — an Islamic revivalism of sorts — that would alter the politics of the whole country for decades.

As the Supreme Court upheld Shah Bano, a divorced Muslim woman who sought the grant of Rs 500 a month as maintenance from her husband, the ulema across North India was up in arms. The Supreme Court judgment was seen as a fundamental breach of the contract between Muslims and the Indian state — the state was interfering in their personal laws.

The cries of “Islam being in danger” reverberated across the country. Millions of ordinary Muslims rallied behind their leaders to protect Islam.

As the cover story of India Today at the time argued: “Not since the pork and the beef fat smeared cartridges caused the great upheaval of 1857 has a single non-political act caused so much trauma, fear and indignation among a community.”

Maulana Abul Hasan Ali Hasani Nadwi of Lucknow’s Darul Uloom Nadwat al-ulama or simply “Ali Miya” as he was lovingly called, a spiritual and intellectual mentor of north Indian Muslims, met then PM Rajiv Gandhi, and convinced him to overrule the judgement.

Rajiv, then a reluctant politician whose mother had just died and who had had close relations with all the ulema who were now prodding him to “save” Islam, obliged.

Several in his own government were alarmed. The Union minister for women in his government, Margaret Alva, pleaded with him to stand up to the religious clergy by reminding him how his grandfather (Jawaharlal Nehru, India’s first PM) had stood up to the Hindu right-wing groups and brought in the Hindu Code Bill despite stiff opposition.

As Alva writes in her 2016 autobiography Courage & Commitment, Rajiv responded by saying: “Yes, my grandfather was a Hindu dealing with Hindu law. Here I am a Hindu dealing with Muslim law. Do you see the difference?”

And like this, the Muslim clergy had been “appeased”, and the BJP, which was desperately trying to make political inroads at the time, found the evidence of Congress’ “pseudo-secularism” that it was waiting for.

Then came the Ramjanmabhoomi movement. Perhaps buoyed by their “victory” in the Shah Bano case, the Muslim clergy — with the AIMPLB and the Babri Masjid Action Committee (BMAC) at the forefront of the campaign — led a fierce campaign to protect Mir Baqi’s mosque from Hindu nationalists. The Muslims of India rallied behind them.

But the mosque stood demolished in 1992. “The ‘Muslim response’ to the cataclysmic event was one of anger, indignation and disbelief,” wrote historian Mushirul Hasan in an essay in 1994, titled Minority Identity and Its Discontents: Response and Representation. “They felt like patients awakening from an anaesthetised slumber after amputation surgery, discovering with pain and frustration that things are never going to be the same.”

One of the things that was never going to be the same again was the Muslims’ unqualified faith in the Muslim clergy to be able to protect them.

As argued by Hasan, the ulema was in disarray. “Having roused religious fervour and made promises to save the mosque, they ‘failed’ to deliver,” he wrote. “They tried to match the Hindu zealots in trying to raise the communal temperature, but when the denouement came, they were nowhere to be found.”

This was the first jolt to their credibility. “They could still gather crowds, adopt benign resolutions, and keep up the pretence of negotiating with ruling and opposition parties,” Hasan wrote. “But their credibility was at the lowest ebb since independence.”

In the immediate aftermath of the demolition, the Shahi Imam issued a call to Muslims to boycott the Republic Day celebrations. It was a damp squib. As journalist Faraz Ahmad wrote for The Pioneer at the time, Muslims’ poor response to his call proved “the losing grip of the old theocracies over the mind of the Muslim populace”.

While the Hindu leaders and activists who had been at the forefront of the Ramjanmabhoomi movement came out as heroes for their community, the Muslim leaders were seen as failures, argues Khwaja Iftikhar Ahmed, author of the book The Meeting of Minds: A Bridging Initiative, which was launched by RSS chief Mohan Bhagwat in 2021.

“Suddenly, there were no heroes for the Muslim community left,” he says.

Also Read: BJP is more interested in Sachar Report on Muslims than Congress now

Swaying away the ‘Muslim vote’

Yet, the narrative of Muslim clerics being able to sway the Muslim vote has survived among politicians and the media over the decades. Before every election, political parties and leaders seek the support of Muslim clerics, who they believe can win them their community’s votes. The few ulema who enter direct politics further enhance this impression.

Hilal Ahmed’s study of Muslim representation in the Rajya Sabha (1953-2014) shows that all political parties, especially the Congress and the Janata Dal (JD), have often used the Rajya Sabha to accommodate prominent ulema in Parliament.

He cites the example of the former president of the Jamiat Ulama-i-Hind, Maulana Asad Madani, who was a Rajya Sabha member from Uttar Pradesh on Congress ticket for three terms (1968-74; 1980-86; 1988-94). There was also Maulana Obaidullah Khan Azmi who was brought to Parliament through the Rajya Sabha in the 1990s by the Janata Dal after he became popular as a result of his fiery speeches during the Shah Bano agitation. After the decline of the Janata Dal, he came to the Congress, which also rewarded him with a Rajya Sabha seat from Madhya Pradesh (2002-2008).

But can Muslim ulema actually sway the “Muslim vote”? According to most scholars of the subject, Muslim leaders, including clerics themselves, the answer is a qualified no.

“You find me one Muslim who has ever voted because of a political fatwa,” says Mehmood Madani, a former Rajya Sabha member himself and president of the Mahmood faction of the Jamiat Ulama-e-Hind. “These are all media-driven narratives,” adds Madani, who has himself extended support to the Congress in several elections.

A CSDS-Lokniti survey on ‘Religious Attitudes, Behaviour and Practices’ conducted in 2015 corroborates Madani’s claim.

According to the survey, the majority of Muslims (43 percent) do not like the ulema to offer support to political parties in elections.

Hilal Ahmed writes in his piece for ThePrint: “Muslims seem to make a very clear distinction between religious concerns and political matters. They do recognise the importance of ulema as intellectuals and expect them to operate in the realm of religious knowledge.”

However, some leaders point out that on ground, these things are far more complicated. “The ulema have traditionally influenced the uneducated, poor Muslims tremendously,” a Muslim Congress leader from Lucknow told ThePrint, requesting anonymity.

“When a poor Muslim goes to a local maulvi for some personal or religious issue, they would also, on the side, tell him whom to vote for,” he says. “The maulvi will give the answer based on what the more influential ulema has decided, or according to his own interest… but these whisper campaigns are common knowledge,” he explains.

When asked how exactly local maulvis go about spreading the word in favour of a political party or candidate without publicly declaring their support, the Congress leader says: “For instance, if they want to support the Samajwadi Party in an SP-BSP contest, they will say khatoon kab kiski god mein jaake baith jaye, nahin pata, toh apna vote samajhdari se dein (we don’t know when and in whose lap the woman may go and sit. So, give your vote wisely).” People get the message, he argues.

While public appeals in favour of political parties may have reduced — the Shahi Imam, for instance, decided to not support anyone in the 2019 Lok Sabha elections — a senior cleric in Lucknow said they still campaign for parties behind the curtains.

“In the 2022 Uttar Pradesh assembly election, we campaigned for the Samajwadi Party, and the whole Muslim vote went to them — it is because they could not bring the Yadav vote that they lost,” he told ThePrint.

“Similarly, in the Karnataka election, we had campaigned for the Congress, and they won,” he adds, referring to the assembly elections in the state last year.

But many point out that these campaigns are just a way for the clergy to keep their importance alive.

“A lot of times, the clergy gauges who Muslims are voting for and they start campaigning for them… later they go about claiming that they made so-and-so win,” Lucknow-based journalist Hussain Afsar told ThePrint. “The truth is that the clergy cannot make someone win in a ward election.”

An increase in education level among Muslims, and a subsequent decline in identification with religious leaders, may also be a factor in the clergy’s waning political influence.

“The influence of the clergy is waning rapidly,” says the Congress leader quoted earlier. “Nowadays, if a cleric is supporting a particular candidate, people are suspicious of an under-the-table deal,” he adds.

Hindutva politics can only be blamed to a certain extent for this discrediting, argues Maulana Siddique. “The Muslim clergy does not have that kind of legitimacy itself,” he says.

“When (former PM and late BJP leader) Atal Bihari Vajpayee used to travel abroad, he used to say, ‘everywhere I go, everyone keeps asking me about Ali Miya’,” Siddique says. “That was the kind of international and domestic respect the clergy held… nowadays, they (the ulema) don’t come close.”

A leaderless community

For many in the Muslim community, 10 years of Modi rule have only made it obvious that Muslims in India are leaderless.

From the legal battle waged by Muslim women against triple talaq in 2017 to the anti-CAA protests in 2019, which were led by ordinary Muslim women in Delhi’s Shaheen Bagh along with young Muslim students, the fact that the Muslim community does not look up to the ulema for political guidance as it once did, is obvious.

“After having trusted the religious leadership for so long, Muslims are now beginning to blame them for their condition too,” the Congress leader says.

Zakia Soman, who spearheaded the campaign against triple talaq in 2017, agrees.

“Over the years, the clergy — or at least the dominant faces in the clergy — became increasingly like the Muslim League,” she says. “They were not bothered about the Sachar Committee report (2006), the backwardness of Muslims, (but) only matters of religious identity.”

Moreover, as “secular” parties begin to increasingly distance themselves from Muslims and their religious leaders, the ulema find themselves in a dilemma.

“There is a thought among Muslims today that we should not campaign for anyone because nobody wants to give us any representation,” says Khalid Rasheed Firangi Mahal.

Yet, it might be premature, and also factually incorrect, to declare that the clergy has become politically irrelevant, argues Hilal Ahmed.

“All past idioms of politics are taking a new shape,” Ahmed says. “In this scheme of things, the ulema are still being approached — but only by the BJP, whose credibility vis-a-vis the Hindu cause is above any doubt.”

Congress’s Khurshid agrees. “Only they can go and present a chadar in the Ajmer dargah now… if we do it, we are accused of minority appeasement,” he says, referring to Modi’s meeting with a delegation of Sufi leaders from the Ajmer Sharif Dargah, to whom he presented a ceremonial chadar.

The outreach by the BJP — especially to the Pasmanda community among Muslims — could slowly reap benefits for it, most Muslim leaders agree.

“Among the ulema and ordinary Muslims, there is a growing feeling — what is wrong with the BJP? What have the others done for us?” says the senior cleric from Lucknow, mentioned earlier.

It is a growing sentiment among several Muslim clerics, who admit that they are in touch with leaders from the BJP and RSS.

The BJP is in mission mode to win some sections of the Muslim vote — the party reportedly aims to expand its voter base among Muslims from the existing 9 percent to 16-17 percent in the upcoming Lok Sabha polls with a special focus on the Pasmandas through welfare measures.

It remains to be seen if ordinary Muslims, pushed into a state of political oblivion, indeed have the same question as the senior cleric from Lucknow — what is wrong with the BJP?

(Edited by Nida Fatima Siddiqui)

Also Read: From Rajiv Gandhi to Modi, nobody defines ‘Muslim appeasement’ but all use it for votes