![]()

As a huge nerd for the history of photography, I’ve spent a lot of time reading about and studying products of the past. And there have been a lot, to say the least.

I previously wrote about some of the most unusual digital cameras ever made. Now it’s time to look back into the analog era and hopefully, you enjoy photography history as much as I do. If so, check out these eight masterpieces of design and ingenuity. Some are weird, some feature truly amazing and unique pieces of technology, and some are just plain cool.

At a Glance

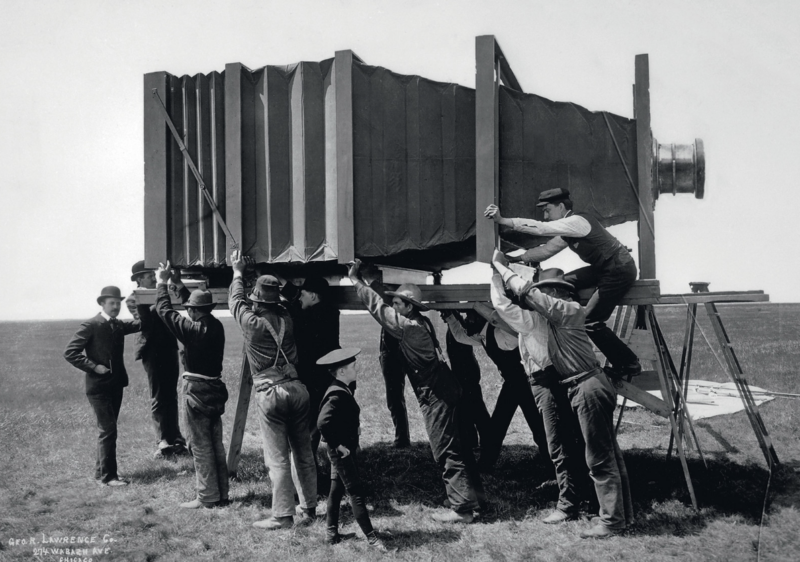

George Lawrence’s Mammoth Camera (1900)

George R. Lawrence was an innovative American photographer known for his pioneering work in aerial photography and his ambitious attempts to capture the grandeur of large-scale scenes. Born in 1868, Lawrence’s fascination with photography and engineering led him to experiment with various techniques and equipment, eventually earning him a reputation as a creative and resourceful inventor. One of his most remarkable achievements was the creation of the “mammoth camera,” a colossal device designed to take the largest photographs ever attempted at the time.

Lawrence’s mammoth camera was conceived in 1900, primarily to photograph the Alton Limited, a luxury passenger train operated by the Chicago & Alton Railway. The task required a camera capable of producing an exceptionally large and detailed image, something beyond the capabilities of standard equipment. Driven by this challenge, Lawrence embarked on the ambitious project of constructing a camera that could accommodate a photographic plate measuring 8 feet by 4.5 feet, an unprecedented size in the history of photography.

To put this in perspective: that’s 2,438 x 1372mm, yielding a 0.0175 crop factor compared to 35mm film or full-frame sensors. A 1000mm lens on such a camera would be the 35mm equivalent of a 17.5mm lens.

Building the mammoth camera was a monumental feat of engineering. The camera itself weighed over 900 pounds and required 15 men to operate. It was constructed with specially designed bellows to handle the enormous plate and a custom-built lens capable of providing the necessary focus and clarity for such a large image. The complexity of the device meant that every aspect had to be meticulously planned and executed, from the sturdy wooden frame to the precise mechanisms controlling the exposure and development of the photographic plates.

The debut of the mammoth camera was a resounding success. The photograph of the Alton Limited was an astonishing achievement, capturing the train in stunning detail and earning widespread acclaim. The image was exhibited at the Paris Exposition of 1900, where it received numerous accolades and solidified Lawrence’s reputation as a master of photographic innovation.

Lawrence later went on to capture his most famous photograph — a panorama of San Francisco in the aftermath of the 1906 earthquake using a 40-pound panoramic camera hung from a series of kites. Click the photo to see a high-resolution version — the detail is truly stunning for a photograph taken 118 years ago.

Ermanox and Ermanox Reflex (1924 / 1926)

In the late 19th century, Heinrich Ernemann founded Ernemann-Werke in Dresden. The company was known for producing high-quality photographic equipment, and the introduction of the Ermanox cameras in the 1920s marked a revolutionary advancement in the field.

The Ermanox camera launched in 1924 was particularly notable for its ability to capture images in low-light conditions without the need for flash, a groundbreaking feature at the time. This capability was primarily due to its fast 100mm Ernostar lens, developed by the renowned optician Ludwig Bertele. The lens had an impressive maximum aperture of f/2.0 (it was later replaced by an 85mm f/1.8 Ernostar), allowing photographers to shoot in dimly lit environments with unprecedented clarity and detail. Keep in mind, the Leica I — released a year after the Ermanox — featured a maximum f/3.5 aperture.

The Ermanox was a compact and portable camera, making it easy to handle and ideal for candid photography. Its innovative design included a focal plane shutter, which was capable of shutter speeds from 1/20 to 1/1000. The combination of a fast lens and a quick shutter made the Ermanox a versatile tool for a variety of photographic situations, from portraits to sports events.

Building on the success of the original Ermanox, Ernemann introduced the Ermanox Reflex in 1926. This model featured a built-in reflex viewfinder, a significant improvement that allowed photographers to compose their shots more accurately and efficiently. The reflex system used a mirror and a ground glass screen to display the exact scene that would be captured on film, making for much more precise focusing and framing. The Ermanox Reflex maintained the same fast Ernostar lens and focal plane shutter as its predecessor, ensuring that it could perform well in low-light conditions while providing the added benefit of through-the-lens viewing.

Ernemann-Werke eventually merged with other companies to form Zeiss Ikon in 1926, and the legacy of the Ermanox cameras lived on through subsequent innovations in photographic technology. The principles established by the Ermanox, particularly the emphasis on fast lenses and portability, continued to shape the design and functionality of cameras in the years to come.

The Ernostar lens would later be modified and developed into the high-speed Zeiss Sonnar lenses used on the Contax rangefinders of the 1930s.

You can find these cameras out there, but you’ll pay a pretty penny for them. I wish I could afford one because they’re a rarely talked about yet pivotal part of photographic history.

Jaeger-LeCoultre Compass Camera (1937)

The idea for the Compass Camera originated from Billing’s vision of creating a highly compact and versatile camera that could rival the performance of larger, more cumbersome models. In 1937, after years of development and refinement, the Compass Camera was introduced to the market. It was an immediate sensation, not only for its technical capabilities but also for its striking and elegant design.

One of the most remarkable aspects of the Compass Camera was its diminutive size. Measuring just over 2 inches in height and 3 inches in length, it was incredibly compact, making it one of the smallest full-featured cameras of its time. Despite its small size, the camera was packed with features typically found in larger models. It was made from lightweight aluminum, which contributed to its portability, and it had a sleek, polished finish that highlighted its sophisticated design.

The Compass Camera was equipped with a 35mm f/3.5 Anastigmat lens, which allowed for high-quality image capture. One of its most impressive features was its capability to take both still photographs and panoramic shots, a rarity for cameras of its size. The camera included a built-in rangefinder, a collapsible viewfinder, and even a compass, from which it derived its name. Additionally, it had an exposure meter and a leveling device, features that were highly advanced for the era.

Jaeger-LeCoultre’s precision engineering ensured that every component of the Compass Camera was meticulously crafted. The company, known for its expertise in watchmaking, applied the same level of detail and accuracy to the camera’s construction. This attention to detail resulted in a highly reliable and durable piece of equipment, capable of performing in various conditions.

Although the Compass Camera was a marvel of engineering and design, it did not achieve widespread commercial success. Its high production costs and complex manufacturing process made it expensive, limiting its accessibility to a broader audience. Only about 4,000 were ever sold, and who knows how many exist today. Nonetheless, it remains a highly sought-after collector’s item today — there is one on eBay in working condition for $4,600 at the time of publication — valued for its rarity and historical significance.

The legacy of the Jaeger-LeCoultre Compass Camera lies in its demonstration of what was possible in camera design and manufacturing. It pushed the boundaries of miniaturization and multifunctionality, inspiring future innovations in photographic equipment. The Compass Camera is a celebrated example of how creativity and precision engineering can combine to produce a truly remarkable and enduring piece of technology.

Also, it’s just really damn cool.

Univex Mercury II (1945)

The Universal Camera Corporation, founded in New York in the 1930s, aimed to produce high-quality, affordable cameras for amateur photographers. The Mercury series was a significant departure from conventional camera designs of the time. Introduced in 1938, the Mercury I featured a distinctive rotary shutter mechanism housed in a prominent dome on top of the camera, which gave it a unique and easily recognizable silhouette. This rotary shutter allowed for faster shutter speeds, making it ideal for capturing action shots and providing greater versatility in various lighting conditions.

Building on the success of the Mercury I, the Mercury II was introduced in 1945. It retained the rotary shutter mechanism but with several improvements and additional features. Unlike its predecessor, which used a proprietary film format, the Mercury II could use standard 35 mm film. Thanks to its half-frame (18×24) format, the camera could take 65 exposures on a single roll of 35mm film, roughly double the number of shots compared to standard full-frame cameras.

One of the standout features of the Mercury II was its built-in exposure meter, a rare and advanced inclusion for cameras of its price range at the time. Additionally, the Mercury II was equipped with a high-quality coated lens — a 35mm f/2.7 Universal Tricor — which contributed to its reputation for producing sharp and clear images.

The Mercury II’s fastest shutter speed of 1/1000th matched the Leica III, but the Contax II and III boasted an even faster 1/1250th by using a vertical (rather than horizontally) traveling curtain. So, Universal developed and released the Mercury CC-1500 with a new top speed of 1/1500th.

Despite its innovative design and features, the Mercury II was produced during a challenging period for the camera industry. The post-World War II era saw increased competition from emerging Japanese manufacturers, which ultimately affected the Universal Camera Corporation’s market position. Also, the rotary shutter, while noted for its accuracy and consistency (something Universal heavily marketed), was prone to jamming. Today it remains a very unique — and cool — page in photography history.

Hasselblad Super Wide Models (1954-2002)

![]()

The Hasselblad Super Wide models, notably the SWA (Super Wide Angle) and its successor, the SWC (Super Wide Camera), hold a distinguished place in the history of photography, both for their uncompromising image quality and absurdly beautiful designs. Introduced by the renowned Swedish camera manufacturer, these cameras revolutionized the way photographers captured expansive landscapes, architecture, and interior scenes.

The story of the Hasselblad Super Wide models begins with Victor Hasselblad’s vision of creating high-quality cameras that could meet the rigorous demands of professional photographers. Founded in 1841, the company initially focused on producing photographic equipment and supplies. However, it wasn’t until after World War II that Hasselblad began to gain international acclaim with the introduction of the 1600F, a modular medium format camera that set new standards for precision and quality.

Building on this success, Hasselblad recognized the need for a camera that could deliver exceptional wide-angle performance. In 1954, the company introduced the SWA (Supreme Wide Angle), the first model in the Super Wide series. The SWA was designed specifically to work with the Carl Zeiss Biogon 38mm f/4.5 lens (a 21mm f/2.5 full-frame equivalent), which boasted a groundbreaking optical design that provided minimal distortion and outstanding sharpness across the entire image frame. This lens was crucial to the SWA’s ability to produce high-quality wide-angle images, making it a favorite among architectural photographers, landscape artists, and photojournalists.

The SWA featured a fixed lens design, which meant that the Biogon lens was permanently attached to the camera body. This design choice ensured optimal alignment and performance — not to mention, due to the heavily recessed rear element, it couldn’t be fitted to any other existing Hasselblad anyway. The camera, like most Hasselblads even to this day, used a leaf shutter mechanism, which allowed for flash synchronization at all shutter speeds — a significant advantage for photographers working in various lighting conditions. Additionally, the SWA’s compact and robust build made it highly portable and durable, suitable for use in demanding environments.

In 1959, Hasselblad introduced the SWC, an improved version of the SWA. The SWC retained the core features of its predecessor but incorporated several enhancements that further elevated its performance. The Carl Zeiss Biogon 38mm f/4.5 lens was updated with new coatings, which improved light transmission and reduced flare, resulting in even sharper and more contrast-rich images. The SWC also featured a redesigned viewfinder that provided a more accurate representation of the wide-angle field of view, aiding photographers in more precise composition.

Both the SWA and SWC were built around Hasselblad’s 6×6 cm medium format system, which offered superior image quality compared to smaller formats. The larger negative size allowed for greater detail, richer tonal range, and better control over depth of field. These attributes made the Super Wide models particularly well-suited for large prints and professional applications where image quality was paramount.

The impact of the Hasselblad Super Wide models on the field of photography was profound. Their ability to capture expansive scenes with minimal distortion and exceptional clarity opened new creative possibilities for photographers. Architectural photographers, in particular, benefited from the cameras’ ability to render straight lines accurately, without the curving or bending often seen in other wide-angle lenses. This capability made the SWA and SWC invaluable tools for documenting buildings, interiors, and urban landscapes.

Landscape photographers also embraced the Super Wide models for their ability to encompass sweeping vistas and intricate details within a single frame. The combination of the wide-angle lens and medium format film allowed photographers to create images with a sense of grandeur and depth that was difficult to achieve with other cameras. The SWA and SWC became essential tools for capturing the beauty and majesty of natural scenes, from mountain ranges to seascapes.

The Hasselblad Super Wide models were not limited to professional use; they also found a place in scientific and industrial applications. Their precision and reliability made them ideal for aerial photography, geological surveys, and other specialized fields where accurate and detailed imaging was required. The cameras’ robust construction and ability to perform in various conditions further solidified their reputation as versatile and dependable tools.

Ultimately, there were five variants — the original SWA and SW, the SWC, the SWC/M, the 903 SWC, and the 905 SWC. The Hasselblad Super Wide Angle system ended after 52 years when the 905 SWC was discontinued.

Hasselblad didn’t forget about it, though. In 2020, it released the 907X 50C, and earlier this year, it unveiled the 907X CFV 100C. The resemblance between the 907x with CFV back and the Super Wide series, especially when the former is combined with the external viewfinder, is unmistakable.

Toyoca 35 (1955)

![]()

Tougodo, founded in 1930 by three brothers-in-law and headquartered in Tokyo, had established a reputation for manufacturing affordable and reliable cameras. In 1955, the company released a camera designed to cater to the growing market of amateur photographers who sought the versatility and convenience of 35mm film but appreciated the unique handling and aesthetic qualities of TLR (twin lens reflex) cameras. It was the Toyoca 35, sometimes called the Toyoca Flex 35.

The Toyoca 35’s design is its most striking feature. While traditional TLRs — such as the Rolleiflex/Rolleicord series — used medium format (usually 120 or 220) film, the Toyoca 35 was built to accommodate 35mm film, making it far more compact and portable. The camera featured a dual-lens system, though even this was unique compared to traditional TLRs. While medium format TLRs used vertically placed lenses (one “viewing” and one “taking”), the Toyoca oriented its lenses side-by-side, horizontally. This setup kept the height of the camera body down while still allowing photographers to compose their shots through the top viewfinder.

The camera’s build quality reflected Tougodo’s commitment to producing durable and user-friendly equipment. The Toyoca Flex 35 was constructed with a robust metal body, and its ergonomic design included straightforward controls for focusing, aperture, and shutter speed. Like medium format TLRs, the Toyoca 35’s taking lens featured a lens shutter mechanism, which allowed for flash synchronization at all speeds. This greatly added to its versatility in different lighting situations.

One of the key appeals of the Toyoca 35 was its affordability. At a time when high-quality cameras were often prohibitively expensive for many, the Toyoca 35 offered an attractive alternative without compromising on performance. This affordability, combined with its unique TLR design and the convenience of 35mm film, made it a popular choice among amateur photographers and photography enthusiasts.

The Toyoca 35 featured a fixed lens — as was common for almost all TLRs. The taking lens was an Owla Anastigmat 4.5cm f/3.5, which provided a very versatile field of view suitable for a wide range of photographic subjects, from portraits to landscapes. The lens was quite capable, too — sharp, contrasty, and all-around exemplary of fine Japanese optical quality.

Despite its initial popularity, the Toyoca 35 faced increasing competition from more advanced and feature-rich cameras as the photographic industry evolved. The advent of more sophisticated SLR cameras and the rise of Japanese camera giants such as Nikon, Canon, and Pentax gradually overshadowed Tougodo’s offerings.

Zeiss Ikon Contarex I (1959)

The Zeiss Ikon Contarex I, often referred to as the “Bullseye” or “Cyclops” due to its distinctive design, was introduced in 1958 by the world-famous German manufacturer Zeiss Ikon. It was the company’s flagship 35mm single-lens reflex (SLR) camera that showcased the pinnacle of photographic engineering and optical precision of its era.

The nickname “Bullseye” or “Cyclops” stemmed from the camera’s unique and prominent selenium light meter, which was centrally positioned above the lens mount and resembled an eye. This distinctive feature not only defined its appearance but also highlighted its advanced metering capabilities. The selenium light meter provided accurate exposure readings, a significant innovation at the time, enabling photographers to achieve precise exposure settings in a wide variety of lighting conditions.

The Contarex I was built with the hallmark quality and precision consistently associated with the German company. Featuring a robust and durable metal body, the camera’s design placed emphasis on its ergonomic handling, with well-placed controls and a solid feel.

One of the standout features of the Contarex I was its interchangeable Zeiss lens system. The camera boasted a range of shutter speeds from 1 second to 1/1000 of a second, and its large, bright viewfinder made focusing and composition pleasurable even in dimmer light.

Despite its unique features, the camera market of the 1960s was rapidly shifting, largely due to the release of the Nikon F the same year. The camera’s complexity and high production costs made it a premium product, and other companies, like Nikon, were releasing more extensive lens lines. However, its legacy endures, and it remains a prized collectible today, celebrated for its innovation, craftsmanship, unique design, and quirky appearance.

Contax AX (1996)

![]()

The Contax AX, introduced in 1996 by Kyocera under the Contax brand, sports one of the most innovative technologies ever developed. The Contax brand — originally established by Zeiss Ikon in the 1930s, was licensed to Yashica in 1973, and Yashica was then acquired by Kyocera in 1983 — had always been defined by a synergy of cutting-edge technology and superior craftsmanship (and paired with world-class Zeiss optics to boot). The Contax AX is no exception.

One of the most distinctive features of the Contax AX is its innovative autofocus system. Unlike conventional autofocus, which moves the lens elements to achieve focus, the Contax AX employs a unique mechanism that moves the film plane itself. This revolutionary design allows photographers to use the gorgeous and impeccable manual-focus Carl Zeiss lenses with the added convenience of autofocus. This feature is particularly advantageous for photographers who want the precision and image quality of Zeiss lenses without sacrificing the speed and ease of autofocus.

The Contax AX’s autofocus system is precise and reliable, capable of focusing accurately even in challenging lighting conditions. The camera’s autofocus mechanism can handle lenses with focal lengths ranging from 35mm to 135mm — quite impressive considering what it’s doing to accomplish this. Additionally, the AX offers multiple focus modes, including single-shot and continuous autofocus.

The AX sports a robust metal body, and its ergonomic design includes well-placed controls and a comfortable grip. It’s actually one of the most comfortable 35mm power-driven cameras to use, at least in my opinion. The Contax AX’s viewfinder is bright and clear, with essential shooting information displayed, aiding in precise composition and exposure adjustments.

Despite its revolutionary autofocus design, the Contax AX faced stiff competition in the rapidly evolving camera market of the mid and late 1990s. The rise of digital photography and the established presence of advanced autofocus systems by other manufacturers like Minolta, Canon, and Nikon, posed significant challenges. And so, ultimately, the camera was a commercial failure. Had it come fifteen or twenty years earlier, it may have had a significantly lasting impact on the camera world.

It remains the only camera ever made capable of autofocusing manual-focus lenses natively (that is, excluding things like Techart’s autofocus adapter for Leica M lenses).