Picture a scorching summer night in Tokyo. You step off the Yamanote Line at JR Ebisu Station and have a sudden, almost subconscious craving for a cold beer.

As the train’s doors begin to close, you wonder why the station’s departure melody is the theme for the 1949 film “The Third Man,” not yet aware the tune is also the Yebisu Beer jingle. As the train clears, billboards advertising Yebisu Beer and illuminated signs depicting the smiling god of the beer’s logo come into view. “A beer would be perfect right now,” you think.

Feeling thirsty, you follow the sweaty crowd out the station’s West Exit, passing a statue of that same god, Ebisu, the lucky patron of fisherman and tradespeople. A large poster for the newly opened Yebisu Brewery Tokyo hangs above him, and it dawns on you that this is a beer town.

In search of a drink, you wander steamy streets lit with lamps shaped like beer mugs or adorned with Ebisu’s jovial face. To escape the heat, you enter an air-conditioned izakaya (traditional Japanese pub) and notice a framed certificate by the entrance declaring they pour a “Perfect Yebisu.” You order one, and as you take that first refreshing sip, you look at the logo on the glass and ponder what other beers are named for their place of origin — Brooklyn Lager, London Pride, Bondi Beach Beer or Sapporo Black Label, perhaps?

But, what you might not realize yet is that Ebisu and its beer are unique in that regard: Here, the beer named the town.

In October, a special-edition beer will be released to commemorate the 30th anniversary of Yebisu Garden Place.

| COURTESY OF YEBISU BREWERY TOKYO

Pouring over history

The story begins in 1887, when Nippon Beer Brewing Company (predecessor of Sapporo Beer) was looking for a site for its new brewery and decided on an area of rural farmland in what is now the Mita area of Meguro Ward, a locale with access to clean spring water from the Mita Yosui, one of the six famous waterways of Edo (old Tokyo). When the three-story brewery was completed in 1889, it was the first modern brick building in the area. Inside, it housed modern brewing equipment from Germany and several German braumeisters were brought in to ensure things were done right.

In February 1890, Yebisu Beer was born, and just two months later it took third prize at the National Industrial Exhibition in Ueno Park. It soon became one of the country’s most popular beers. In August 1899, Japan’s first beer hall opened in what is now the Ginza Ha-chome district. It was, of course, Yebisu Beer Hall.

This was followed by international recognition, with the beer winning the gold prize at the Paris Exposition in 1900 and later the grand prize at the Louisiana Purchase Exposition in 1904.

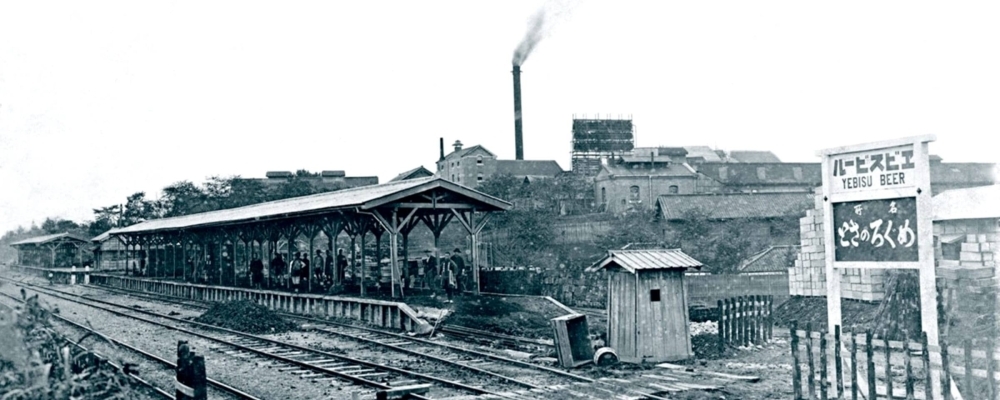

In 1901, the Yebisu Beer Depot station opened to facilitate the distribution of the increasingly popular beer.

| COURTESY OF SAPPORO BREWERIES LTD.

As demand increased, Nippon Beer needed a way to handle its increasingly large shipments of beer and requested that Nippon Railways build a dedicated cargo station beside the brewery. In 1901, the Yebisu Beer Depot station opened.

By this time, locals were already giving beer-related nicknames to features around the factory. In particular, a street by the brewery was named Biru-zaka (Beer Hill), which remains to this day.

As the factory expanded, so did the population nearby, and in October 1906, a station was added to the Shinagawa Line (predecessor to the Yamanote Line), where JR Ebisu Station stands today. At the time, the area was still known as Date-ato, in the district of Shimoshibuya, but in January 1928, the station precinct was officially unified under the name Ebisu-dori (Ebisu Street), becoming the first, and only, neighborhood in the world to be named after a station that was named after a beer. You can’t help but think a few glasses of Yebisu were raised that day!

Drinking buddies

Nearly a century later, ties between the Ebisu community and its beer are still strong.

At the annual summer Bon festival, for example, locals dance to songs such as “Hey Mr. Ebisu!” and “Yes! Yes! Ebisu” with lyrics about drinking beer: “Let’s have a drink tonight. All night long, let’s have a toast.”

Other annual beer-related events that bring the community together include the Beer-zaka Matsuri and the Aloha Tokyo festival, as well as the more traditional Hikawa Shrine Festival and the Bettara-ichi pickles festival at Ebisu Shine.

Yebisu beer is such an indelible part of the fabric of the Ebisu community that the brewery’s name is inscribed into the century-plus-old “mikoshi” (portable shrine) from Shibuya Hikawa Shrine.

| COURTESY OF KENJI TAKAHASHI

Recently, a group of Ebisu residents started Awa Ebisu, a civic initiative aimed at protecting these traditions.

The group’s name has a double meaning, as “awa,” the Japanese word for foam (like that on a head of beer), sounds like “our” in English and captures the community’s tight connection with the beer that gave their home its name. This is “Our Ebisu,” but it’s also your Ebisu.

Awa Ebisu activities are supported by Sapporo Beer Company, which has its headquarters in Ebisu and owns the Yebisu Beer brand. Kenji Takahashi, group member and editor-in-chief of the Ebisu Journal, explains the beer company has been closely involved with local festivities for the past 124 years.

“In 1900, an impressive Edo-style mikoshi (portable shrine) was created with the support of the townspeople and the Shibuya Hikawa Shrine parishioners’ association,” he says. “The mikoshi was stamped with the inscription ‘Yebisu Beer Company,’ indicating that Yebisu Beer was already an essential part of the festivals at that time.”

Takahashi says that one purpose of Awa Ebisu is to “protect these traditional festivals and to preserve the portable shrines.”

Awa Ebisu member Kenji Takahashi says that one purpose of the community group is to safeguard festivals and shrines for future generations.

| COURTESY OF KENJI TAKAHASHI

To raise money, the group coordinates with Sapporo Beer to sell Yebisu at local events, and the proceeds are donated to ensure the future of these festivals.

“We are also working to nurture the children in the area, who will protect the festivals in the future,” says Takahashi. “ We want young children to have fond memories of festivals. As they grow, we can then entrust them with small roles until they are able to manage the (events).”

In the spirit of full disclosure, I should point out that I was invited to join the Awa Ebisu group last year, due to my habit of completing the annual Yebisu Beer x Ebisu Food Grand Prix. As a member, I’ve seen firsthand the pride people living here have in the history of their town and how closely Sapporo Beer works with the community.

Ryouta Aritomo, the chief brewer of Yebisu Brewery Tokyo, helped bring in hops from Germany for the creation of a special anniversary brew.

| COURTESY OF YEBISU BREWERY TOKYO

In 1988, when the original brewery closed and production was moved to Funabashi in Chiba Prefecture, many lamented the fact the beer would no longer be made locally.

Hiroyuki Mantani, Awa Ebisu member and manager in charge of Yebisu Brewery Tokyo, tells me that in the 1990s, when construction of the Sapporo Beer headquarters and the Yebisu Garden Place complex began on the site of the old brewery, “there was actually a plan to build a mini-brewery within the head office, but the idea was abandoned at that time for a variety of reasons.”

Instead, a history museum was built showcasing the brand’s history with tours and a Yebisu Beer tasting salon. In 2019, however, it was decided it was time to bring beer-making back to the birthplace of Yebisu, and the museum was closed in October 2022 for refurbishment.

In April 2024, Yebisu Brewery Tokyo opened with a taproom featuring several exclusive beers brewed onsite, including Yebisu Infinity, which uses the original variety of German hops and the same yeast strain used in the 1890s.

In April, Yebisu Brewery Tokyo opened, returning the beer to its rightful place since the closure of the previous brewery in 1988.

| COURTESY OF YEBISU BREWERY TOKYO

“We are very happy that 35 years after the closing of the factory, brewing has actually resumed here,” says Mantani.

To bring things full circle, Sapporo Beer has a new project to involve the community in the brewery. In October, a special-edition beer will be released to commemorate the 30th anniversary of Yebisu Garden Place. Working with Ryouta Aritomo, chief brewer of Yebisu Brewery Tokyo and Awa Ebisu member, a group of local residents is actually growing hops in a small garden by JR Ebisu Station’s East Exit.

“We received the seedlings from the Hallertau region in Germany,” Aritomo says. “It is very emotional for me to grow German hops in Ebisu.”

Through the project, Aritomo hopes people will learn about the ingredients of beer and Ebisu’s historic connection with Germany — tying together the places, the people and the beer company that have made Ebisu what it is today.

Beer labels

To clear up any confusion, “Yebisu” and “Ebisu” are both pronounced “Ebisu.” But due to the first romanisation of Japanese by a Portuguese missionary in the 1600s — who decided to transliterate “エ” (or the archaic “ヱ”) as “Ye” — the roman spelling of many words during the Meiji Era were written in this style: “Yedo” rather than “Edo,” for example. For this reason, Japanese first thought that the sound “eh” should be written as “ye,” and since it was first released in 1890, the roman letters “Yebisu” have been used in the beer’s trademark, while the Japanese is “ヱビス.”