Akira Toriyama wasn’t just a Japanese manga artist responsible for several popular franchises. When his death at the age of 68 was announced last week, it soon became apparent just how much of an impact he had on millions of people around the world.

“I heard about Toriyama-sensei’s passing the moment it was announced,” says Jason, a YouTuber who asks to only go by his first name and refers to Toriyama with the Japanese honorific for “teacher.” Jason is the creator behind the channel Carthu’s Dojo, which is devoted to all-things “Dragon Ball,” Toriyama’s best-known creation. “I sat in my chair just thinking about how Toriyama-sensei had greatly changed the trajectory of my life more than (even my) relatives had. I’m not one to get emotional over celebrity deaths, but I openly wept for this one.”

After the animator’s office shared news of Toriyama’s death due to acute subdural hematoma (a blood clot in his brain), users of social media networks from X (formerly Twitter) to Weibo to Instagram shared messages of shock followed by tributes expressing just how much his work meant to them.

Akira Toriyama, the creator of “Dragon Ball,” seen in a file photo from 1982.

| KYODO

First, tributes poured in from Toriyama’s peers. There were messages from “One Piece” creator Eiichiro Oda and “Slam Dunk” creator Takehiko Inoue, and the titular character of “Archie” was depicted standing next to Toriyama’s Goku character in celebration of the creator’s legacy. Then, the fans weighed in. Among them were celebrities from various fields, including Hong Kong martial arts icon Jackie Chan, who posted a shot of him and the artist on Weibo saying, “Farewell, Toriyama-sensei”; pop star The Weeknd posted a screenshot from “Dragon Ball” on Instagram; and reigning basketball MVP Joel Embiid expressed disbelief on X.

The tributes only got bigger. China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs offered its condolences, while French President Emmanuel Macron shared his autographed Toriyama illustrations. The government of El Salvador called for a day of mourning, and crowds of people gathered in the streets of Mexico, Argentina and Chile, to name a few countries, to celebrate Toriyama’s legacy by miming Goku’s “spirit bomb” move — hands raised in the air with palms upward to gather energy before hurling it at an opponent.

Argentina was just one of the countries that saw a public display of mourning after the death of Japanese manga artist Akira Toriyama.

| REUTERS

These public displays of mourning proved Toriyama wasn’t just an artist. He exists in the same echelon of people as animator Walt Disney (1925-66) and Marvel creator Stan Lee (1922-2018). All three of these individuals, Toriyama included, had a personal artistic style that has become the shorthand for their respective media.

“Dragon Ball” loomed large over manga and anime, but even those from a generation prior would have encountered Toriyama’s distinctive drawings for the “Dr. Slump” manga. His character designs grace the Dragon Quest series of video games along with the critically acclaimed 1995 role-playing game “Chrono Trigger,” meaning decades of gamers have also been exposed to his work.

Still, “Dragon Ball” proved to be Toriyama’s magnum opus and Goku his Mickey Mouse or Spider-Man. The character, and the roster of supporting faces introduced in the series, are recognizable in nearly every corner of the globe — often, they were non-Japanese children’s first introduction to the world of Japanese anime.

“Back in the mid-2000s, the street culture in Akihabara was very active, and I was conducting fieldwork — specifically participant observation and ethnographic interviews,” says Patrick W. Galbraith, an associate professor at the School of International Communication at Senshu University and author of several anime-related books, including “The Otaku Dictionary: An Insider’s Guide to the Subculture of Cool Japan.” In the course of his research at the time, Galbraith opted to dress as a character to fit in on Akihabara’s streets, opting for Goku because of his easy recognizability. He says it helped him in approaching potential interview subjects.

“As things progressed, however, I was totally and utterly shocked by the effect that the costume had on people,” Galbraith continues. “Young and old, male and female, Japanese and foreign — seemingly everyone wanted to pose with me and say lines from ‘Dragon Ball.’ I learned then, feeling it in the flesh, just how important this character was to generations of fans.”

Timing is everything

Despite being a generation’s introduction to anime, “Dragon Ball” wasn’t the first example of the art form to make its way into the greater world.

Japanese works such as “Astro Boy” and “Speed Racer” appeared on TV sets beginning in the 1960s, as did a hodgepodge of titles ranging from redubs of the toddler-geared “Maple Town” to anime versions of literary classics like “Little Women.” Productions aimed at older audiences — including Katsuhiro Otomo’s “Akira” (1988) — circulated, but they were still cult sensations that were years away from mainstream exposure.

By the time U.S. production company Harmony Gold first took a crack at bringing a dubbed version of “Dragon Ball” to America in 1989, Toriyama’s creation had become a sensation in Japan. Growing up in Aichi Prefecture, he developed an interest in manga as a child in part after reading Osamu Tezuka’s “Astro Boy.” He didn’t really pursue it, though, until he needed to make some money, which he did in the late ’70s by entering an amateur contest. This led to more work, breakthrough success with “Dr. Slump” and, in 1984, the start of a series inspired by kung-fu movies.

“Dragon Ball,” published in Weekly Shonen Jump, became a hit. Galbraith notes that the publication saw its circulation numbers skyrocket during the period in which Toriyama was most involved.

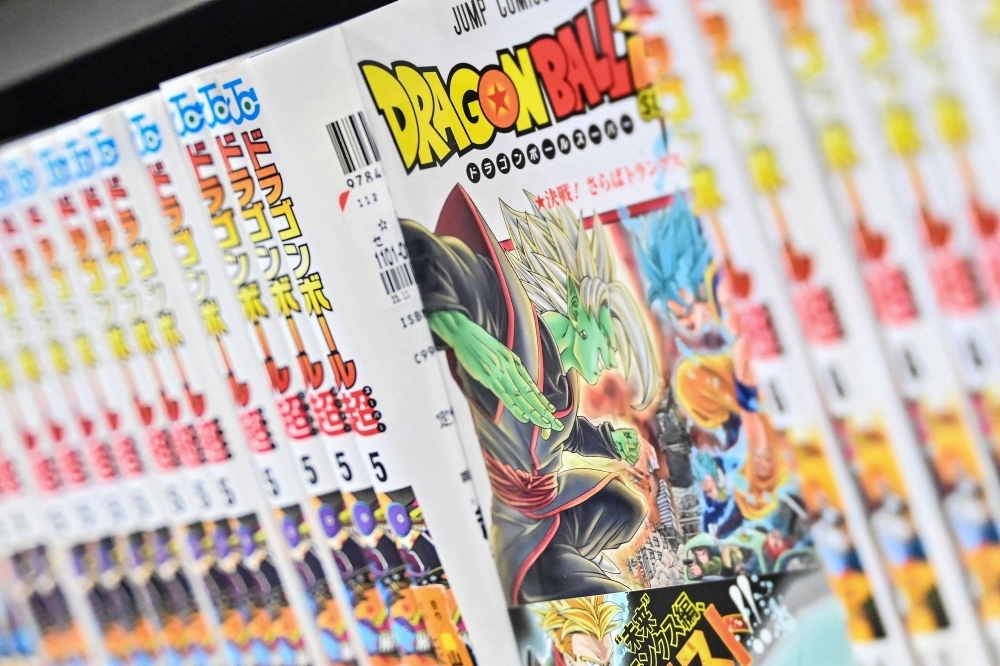

Books from the “Dragon Ball” manga series sit on a shelf in a store in downtown Tokyo.

| AFP-JIJI

“I don’t think anyone understands paneling the way Toriyama-sensei does,” Jason of Carthu’s Dojo says. “His ability to seamlessly lead the reader’s eye across the page, taking you from scene to scene without you having to think about where you’re looking next is genuinely incredible and hard to explain without just reading his work.”

It took some time for “Dragon Ball” to find its footing abroad. Harmony Gold’s effort resulted in a lackluster dub that gave every character a new name. Goku became “Zero.” It didn’t last long in the few markets where it aired. Efforts that were truer to the original, specifically through the series “Dragon Ball Z” (1989-96), not only helped break the franchise into North America but ushered in an anime boom.

“It was a combination of ‘Dragon Ball Z,’ ‘Sailor Moon’ and ‘Pokemon’ that made anime into popular culture there. When you think of action-adventure manga and anime, Toriyama’s work comes up as the archetype,” Galbraith says, noting that programming blocks such as Cartoon Network’s Toonami played a massive role in spreading the style.

Toriyama became less involved with “Dragon Ball” during the bulk of the 2000s but came back on board in 2013.

“The series has a much larger economic footprint in the anime industry today than it did just 10 years ago, thanks to Toriyama’s personal involvement in ‘Dragon Ball’ anime projects since 2013,” says Richardson Handjaja, an anime industry journalist serving as the publisher and editor of Animenomics. “One estimate by entertainment researcher Atsuo Nakayama put total sales of ‘Dragon Ball’ media and merchandise worldwide above ¥550 billion (US$3.7 billion) in 2022.”

From manga to anime to merchandise, a figurine of a character from “Dragon Ball” is just one way fans can express their love for the series.

| AFP-JIJI

Galbraith says Toriyama “cracked the code” for hit shōnen manga serials, the kinds of adventure titles targeted at young boys, “and he offers the template for current smash hits such as (Gege Akutami’s) ‘Jujutsu Kaisen.’” Toriyama went beyond encouraging new artists, though. He influenced the style of anime as a whole and revealed new economic potential, as the comic series mutated into an anime, video games and infinite merchandise. “One can sense the DNA of Toriyama’s work in all subsequent shōnen releases,” Galbraith adds.

Critically, Toriyama’s efforts showed just how far anime could travel in the world, making it one of the greatest forms of pop culture soft power we’ve ever seen.

Global saga

Edgar Pelaez remembers coming home from school during his childhood in Mexico and watching the original “Dragon Ball.”

“I think at that time it hadn’t yet exploded in Mexico, but it was something to watch after coming back from school,” says Pelaez, an adjunct professor of sociology at Lakeland University Japan who has researched heavily in the fields of anime, manga and fan culture. He recalls the first episode of “Dragon Ball” he ever saw was one where female character Bulma flipped off the show’s antagonist.

“I just laughed so hard — that was so uncommon to watch on TV,” Pelaez says. “The first thing I thought was, ‘Yeah, if you get pissed, that’s a natural reaction!’ From then on, I kept watching.”

To truly understand the popularity of “Dragon Ball” — and anime at large — witness the outpouring of tributes from Latin America. Save for Japan itself, no region has embraced Toriyama’s work quite like countries there have, and in the wake of his death, almost all public displays of mourning came from the region. The X account Crazy Ass Moments in LatAm Politics collected various reactions to Toriyama’s death from Latin American politicians in a thread that included tributes from Brazil, Costa Rica, El Salvador and more. Want to endear yourself to Latin American voters? Make sure your respect for “Dragon Ball” is well-known.

Like the rest of the world, anime has appeared in Latin America for decades in the form of “Astro Boy” and other novelties. As anime entered a golden era in the 1990s, though, Pelaez says economic factors were right for a show like “Dragon Ball” to boom in Mexico, pointing to the 1994 North American Free Trade Agreement, which prompted the arrival of more privatized TV stations. “These new companies didn’t actually have any content per se.”

Argentine “Dragon Ball” fan Alexis Siri, 39, holds his son, Noah, 5, who is dressed as Vegeta, as they bid a final farewell to Japanese manga creator Akira Toriyama, at the Obelisk in Buenos Aires.

| REUTERS

One fledgling station, Television Azteca, acquired the rights to the series “Saint Seiya,” and, as Pelaez recalls, the animated action was like nothing anyone in the country had seen before (“The characters are fighting, and there’s blood everywhere”). To compete, rival broadcaster Televisa brought “Dragon Ball” over.

“Everybody was watching it,” Pelaez says, adding that its popularity was such that it was aired in the prime-time evening slot (going up against another favorite import — “The Simpsons”).

“With Goku, you might not be the strongest, but if you work really hard, you can be. That’s something that resonates a lot in Latin American culture,” Pelaez says. “Especially when you think about the economic differences that exist in the country, in the region — the fact that you can improve your life by working hard really resonates.”

Further beyond

In almost all the public reflections on Toriyama’s life, fans reveal just how much his work has changed their lives on a personal level.

“The anime adaptation aired on Indonesian TV in the 1990s,” Handjaja says. “Seeing young Goku defeat opponents that were bigger and stronger than him encouraged me to be more courageous as a young child.”

“Not only would I not have my current YouTube channel without him,” says Carthu’s Dojo’s Jason, “but I’d never have studied karate either, which was a massive part of my youth.”

Monterrey mascot “Monty,” poses dressed as Goku in memory of Akira Toriyama before the start of the Mexican Clausura 2024 tournament football match against Mazatlan at the BBVA Bancomer stadium in Monterrey, Mexico.

| AFP-JIJI

In “Dragon Ball” and Goku, all kinds of people have found inspiration. The American rapper RZA wrote in his 2009 book “The Tao Of Wu” that “Dragon Ball Z” represented “the journey of the Black man in America.” In fact, Black men as a demographic embraced the show, and it continues to be referenced in modern hip-hop and professional sports.

Numerous people have also held up Goku as a fitness role model, using him as inspiration to unlock their physical potential through “Super Saiyan sets” (a reference to a Goku’s transformation in a hyper-powered physical form).

“I think children who grew up on Toriyama’s works are attracted to the characters he created that appear helpless but are actually stronger and more capable than they look,” Handjaja says. “Arale in ‘Dr. Slump’ and young Goku in ‘Dragon Ball’ have naive personalities, but both have amazing strength and are not afraid of challenging the adults around them.”

Argentine Dragon Ball fans perform a “Kamehameha” move as they bid a final farewell to Akira Toriyama in Buenos Aires.

| REUTERS

In Latin America, Pelaez sees a more familial connection. “It’s one of the few media franchises to have the elasticity to go beyond one generation. We have people who watched ‘Dragon Ball,’ who passed it to their sons, and now they have grandchildren watching. It brings those from different generations together.”

While the world mourned Toriyama’s loss, the power of his art and the inspirational characters aren’t going anywhere.

“I will always remember Toriyama as a legend whose work changed the game, the world and my life. His work opened my eyes to the world of shōnen manga and anime,” Galbraith says. “When I think of powering up before my next challenge, I always return to Goku. That character is part of me now, and part of our collective consciousness.”