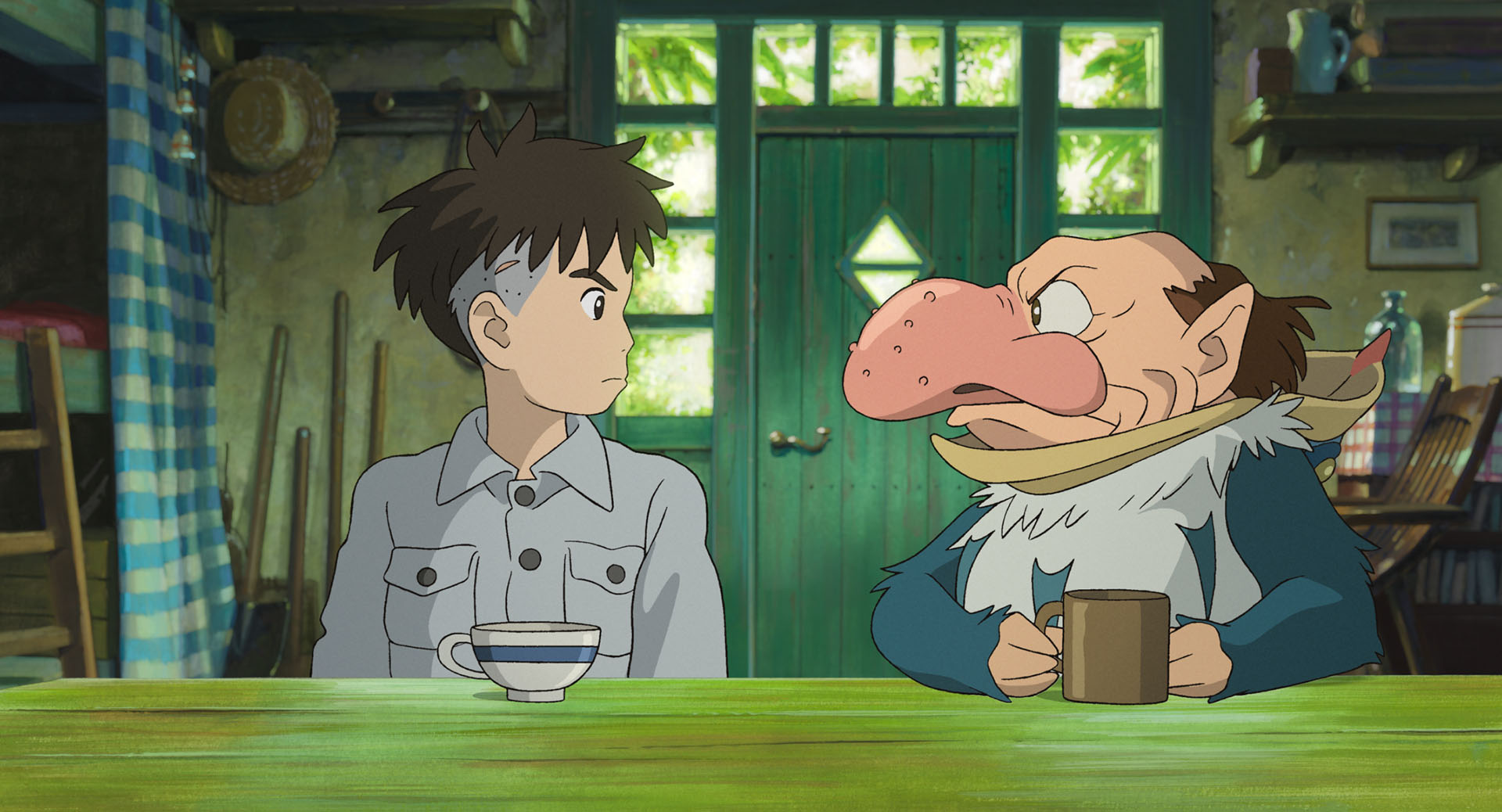

rewrite this content and keep HTML tags Hayao Miyazaki’s latest film, “The Boy and the Heron,” features the tense and humorous relationship between a boy and a magical bird.Courtesy of Studio GhibliIn many ways, Hayao Miyazaki’s new film, “The Boy and the Heron,” resembles his 2001 masterpiece, “Spirited Away”: A displaced and homesick child takes a journey through a magical portal to a dangerous, dreamlike land to save their family.“The Boy and the Heron” bears allusions to Studio Ghibli’s vast 37-year body of work, but it’s notable that Miyazaki has once again returned from retirement to create this film. “The Boy and the Heron” doesn’t simply rehash what we expect from Miyazaki (cozy, magical, feminist); instead, the movie expands his prior themes to form a meta story about what it means to create magical worlds and the necessity and peril of passing that work on to one’s descendants. Also, there are flocks of 7-foot-tall parakeets whose empire seeks to conquer everything.Huddled in a light drizzle outside the CineArts Sequoia in Mill Valley on Monday night for the Mill Valley Film Festival’s West Coast premiere of “The Boy and the Heron,” the first of three sold-out showings at the festival, Studio Ghibli fans chatted about their excitement for Miyazaki’s latest work and reminisced about their favorites. AdvertisementArticle continues below this adFor Gwen Hicks, who stood in line just ahead of my movie companion and me, nothing could quite match 1986’s “Castle in the Sky.” For Zack Adams, an MVFF member who has attended six screenings so far this festival, 1988’s “My Neighbor Totoro” was the movie to which he returned most often, finding new depth in it as an adult. My movie companion, my 18-year-old stepchild, reminisced about 2008’s “Ponyo,” the first Studio Ghibli movie she saw in theaters, and I mentioned 1992’s “Porco Rosso” and 2004’s “Howl’s Moving Castle,” with their themes of war and redemption. Flavors of all these films are in “The Boy and the Heron,” which opens with a visually stunning and overwhelming sequence of a hospital on fire, the titular boy, Mahito, running desperately through the throng to save his mother. The animation here resembles watercolor, dramatically blurring both Mahito and the crowds to create urgency and peril in an impressionistic way. We lose hope that the hospital and his mother can be saved, but the carnage ends almost as suddenly as it began. Mahito and the audience are whisked away to a quiet countryside, safe from the terrors of war but presented with a new set of terrors. Mahito’s father marries Natsuko, the little sister of Mahito’s mother. While his “new mother” cares for him dutifully, she is already pregnant with his sibling. His father disappears to run a factory, and he is left alone in a quiet house with his grief. Then, in Miyazaki fashion, a gray heron (with ominous teeth) summons him to a mysterious tower in the woods. AdvertisementArticle continues below this ad“The Boy and the Heron” explores motherhood and family when the protagonist’s mother dies and his father takes a new partner.Courtesy of Studio GhibliMahito resists the summons, but when Natsuko disappears into the woods, Mahito goes to rescue his stepmother, much as he tried to do with his mother in the opening scenes. In the woods, he finds a portal to a mysterious and intricate world with totally alien rules of physics. When the wind rises, so does the tide; one mustn’t under any circumstances open the ornate gold gate; and the main inhabitants of this watery place are enormous carnivorous pelicans and parakeets. As with most Miyazaki films, I simply let myself be swept — dare I say spirited — away by the experience. Did I understand how the tower had turned into a vast ocean inhabited by ships of the dead? Or why the enormous parakeets had taken over the blacksmith shop? Or why you should never ever open that gold gate? No, but I relished spending 124 minutes in Miyazaki’s lush, dreamlike world, and I have a feeling I’ll find new things to spot and appreciate with each rewatch, just as I do with movies such as “Spirited Away” and “Howl’s Moving Castle.”The sound design of “The Boy and the Heron” powerfully enhances the experience. The calls of insects and birds punctuate the silence of the sparse countryside. A single piano note marks the beginning of contact with the other world. In tense scenes, the music falls away, and we hear only the sounds of predatory parakeets, breathing softly as they hungrily anticipate their next meal.AdvertisementArticle continues below this adHayao Miyazaki’s latest film, “The Boy and the Heron,” explores themes of creation and legacy.Courtesy of Studio GhibliBy the end of the film, as the otherworldly origins of the tower are revealed, it’s clear why Miyazaki returned from retirement to make “The Boy and the Heron”: He is exploring creation and storytelling and how even the best-intended endeavors can be twisted by our own malice. Sitting in the packed theater beside my stepchild, whom I’ve had the privilege of helping to raise for a decade now, I couldn’t help but feel my eyes spill over with tears, thinking of all the ways parents strive to give their children a perfect, peaceful world — and all the ways we inevitably fail. But despite that failure, the work is never finished. Though he has retired numerous times before and returned each time to give us movies such as “Spirited Away” and “Ponyo,” this time around, Studio Ghibli says, Miyazaki has no intention of retiring: He’s already hard at work on his next film.

Hayao Miyazaki’s comeback film premieres at Mill Valley Film Festival

Denial of responsibility! Swift Telecast is an automatic aggregator of the all world’s media. In each content, the hyperlink to the primary source is specified. All trademarks belong to their rightful owners, all materials to their authors. If you are the owner of the content and do not want us to publish your materials, please contact us by email – swifttelecast.com. The content will be deleted within 24 hours.