![]()

Aleksandr Gordiychuk is hopping around the world, earning a living by repairing old and broken cameras.

Ukrainian and Russian Roots Poses Many Challenges, Personal and Professional Alike

Born in Ukraine to Ukrainian parents who now live in Russia, Gordiychuk has since left Russia and can no longer return to Ukraine. He must be paid for his work in crypto because he faces extensive sanctions worldwide. He can no longer repair cameras from the United States or Canada either.

“My mother and father are in Russia. They are both from Ukraine,” Gordiychuk tells PetaPixel. “My mother’s relatives live in Ukraine, and my father’s relatives live in Russia, but they are also from Ukraine. Russians and Ukrainians are brothers, and we have always lived together, but this war tore people apart. My relatives in Ukraine communicate with me, and we follow each other on social networks.

“I miss my village in Ukraine, but I can’t go there.”

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

The camera repairman also faces challenges on where he can go.

“Even Airbnb will ban me if I open their site from Russia. So, these sanctions have made it much more difficult for Russians to leave Russia and not sponsor our government with taxes. Sanctions have the opposite effect. Of course, you can leave and overcome difficulties, but this psychological effect only makes things worse. People in Russia don’t understand why they should be punished if they are already punished by the dictatorship of the government. Sanctions don’t work for the elites. They don’t work for people who have money,” Gordiychuk says.

Where is Gordiychuk Now?

He recently went to Kazakhstan for three months and is now in Thailand. “In Kazakhstan, I received a lot of cameras by mail,” Gordiychuk explains.

“Before choosing Thailand, I checked its customs limits and visa requirements. Until I was in Kazakhstan, I asked my friend to send cameras from Russia to Vietnam, Malaysia, and Thailand to check how they would pass the customers. They all passed, but in Vietnam and Thailand, people told me that cameras will not pass without fees.”

As it turns out, Thailand does not impose the fees people told Gordiychuk about, so he is sure to check everything for himself. “This is one of the features of my work and the reason why I succeed — I don’t listen to anyone and check everything myself because it often turns out that people are wrong, and until you try it yourself, you won’t know the truth.”

Since Gordiychuk travels with his tools and earns money in foreign countries, there’s always the chance that he may face issues at a border or perhaps even be deported. However, he doesn’t think it matters much where he earns money remotely or repairs cameras for locals.

The war in Ukraine has affected many people in diverse, horrible ways. For Gordiychuk, with his Russian family and Ukrainian roots, it has been very challenging from a personal perspective. When Russia mobilized its army, Gordiychuk picked up and left Russia.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

“I was terrified but not ready to leave everything. I started selling all my cameras, I had too many. I transported unnecessary things to my mother’s house in Tolyatti [a city in western Russia] and prepared to leave the country, if necessary,” Gordiychuk says.

“I took all the necessary stuff, like my tools, parts, and even my Nikon Coolscan V slide scanner. But I left my microscope and soldering station. I then bought it in Kazakhstan.”

This abrupt departure was disrupted a couple of months later, as Gordiychuk missed his job as a service engineer in Moscow working for a Japanese company.

Honing His Craft

The service center position was a great boon for Gordiychuk, as it taught him how to repair a wide range of cameras.

“In this company, I was able to repair equipment without replacing the entire unit with a new one, but I found the root cause and could eliminate it because I understood how each unit in the device works,” he says. “Now I believe that I am capable of solving the most complex problems in photographic equipment and am interested in film equipment but have not yet encountered it. I’ve had to repair serious slide scanners, but never serious movie cameras.”

He adds that the center’s general director and head are “two of the best and most respected employers in my life.”

However, the sanctions on Russia affected this job, too, and the Japanese company was forced to reduce its staff by half. Gordiychuk realized that his earnings as a camera repairman on the side outpaced his actual salary, so “this was a sign” for him.

“I moved all my extra things to my mother’s house, left a rented apartment in Moscow to my father, and left the country with two suitcases of 23 kilograms (about 50 pounds) each and a backpack.”

![]()

![]()

“They contained all my things. I’m still looking for a way to throw away the excess. It’s hard to do, but I have no right to complain.”

Learning by Doing

Gordiychuk’s current nomadic camera repair lifestyle has been many years in the making. Despite having no formal education in electronics or mechanical engineering — he dropped out of a university program in architecture — his father has long been enthusiastic about electronics.

“My father was into electronics seriously. He told me as a child what electricity is, voltage, current, what elements there are, and what they do. He helped me make an AC/DC converter with voltage regulation when I was about 13 years old. He repaired tape recorders, televisions, and game consoles in the 90s in addition to his main job. It was cool then,” Gordiychuk says. “I never thought about it, but it looks like I followed in his footsteps.”

When he was eight or nine, Gordiychuk dismantled a new tape recorder while his parents weren’t home. He often tinkered with microcircuits and was once able to get into his grandfather’s old Zenit 3M camera with an Industar 50mm prime lens. “The shutter and mirror in the camera were jammed, but the lens was very interesting to me, so I disassembled it with scissors.”

![]()

![]()

He repaired his first camera and lens in 2007: a Zenit Et and Helios 44M.

“I lived in a small town and was severely limited in opportunities and prospects. In 2011, I bought a Mamiya 7 and serviced it by myself. It had rangefinder misalignment and exposure metering problems,” he says.

“Then I began to be interested in repairing complex cameras with electronics.” Unfortunately, there was not a lot of information on the topic for Gordiychuk to consume.

The Online Repair Community

He took to the internet, where he learned about Kenneth Olsen on YouTube, who goes by the name mikeno62. “I was amazed by his knowledge of Mamiya 7 malfunctions. I think I started publishing reports on my own repairs because of him,” he says.

“After that, I found an enthusiast with the nickname MinoltaKid. He described how he repaired his Leica Minilux. I looked at his photographs, and this was enough for me to understand how to disassemble the camera and how to repair it.” The post is still available online.

![]()

“I looked at his photographs and this was enough for me to understand how to disassemble and repair the camera. After this, I thought I could fix this camera by myself, and I bought a broken Leica Minilux. At that time, I did not have sufficient soldering skills and did not understand the principle of repairing a broken flex cable. So, I disassembled the camera, found the broken point, and restored the broken contacts with a wire.”

This repair held for a while, although, unfortunately, Gordiychuk fell off his bike and broke the camera again. “I managed to shoot 30 frames, and they were great, so I kept searching for the best way to fix this camera.”

Working in Moscow

In 2017, he moved to Moscow to live with his father and almost immediately started a new job at a film lab. “I already had a background in developing film (six years) and scanning (eight years).”

Knowing that Gordiychuk was a budding camera fixer, the photo lab’s technical director gave him a broken Contax camera that the director had lost hope in repairing himself. “I also couldn’t fix it and didn’t believe it was possible to fix. The camera was much more complex than the Leica Minilux,” Gordiychuk admits.

Putting this puzzle aside “for years,” Gordiychuk continued in Moscow. He met the only slide scanner repairman in Russia, Sergei Zykov, known locally as “The Man in the Hat.”

![]()

![]()

“He had his own shop in which he repaired mainly Nikon Coolscan of various models he had his own fully equipped workshop with a microscope and a studio for listening to and repairing high-end players and amplifiers,” Gordiychuk says.

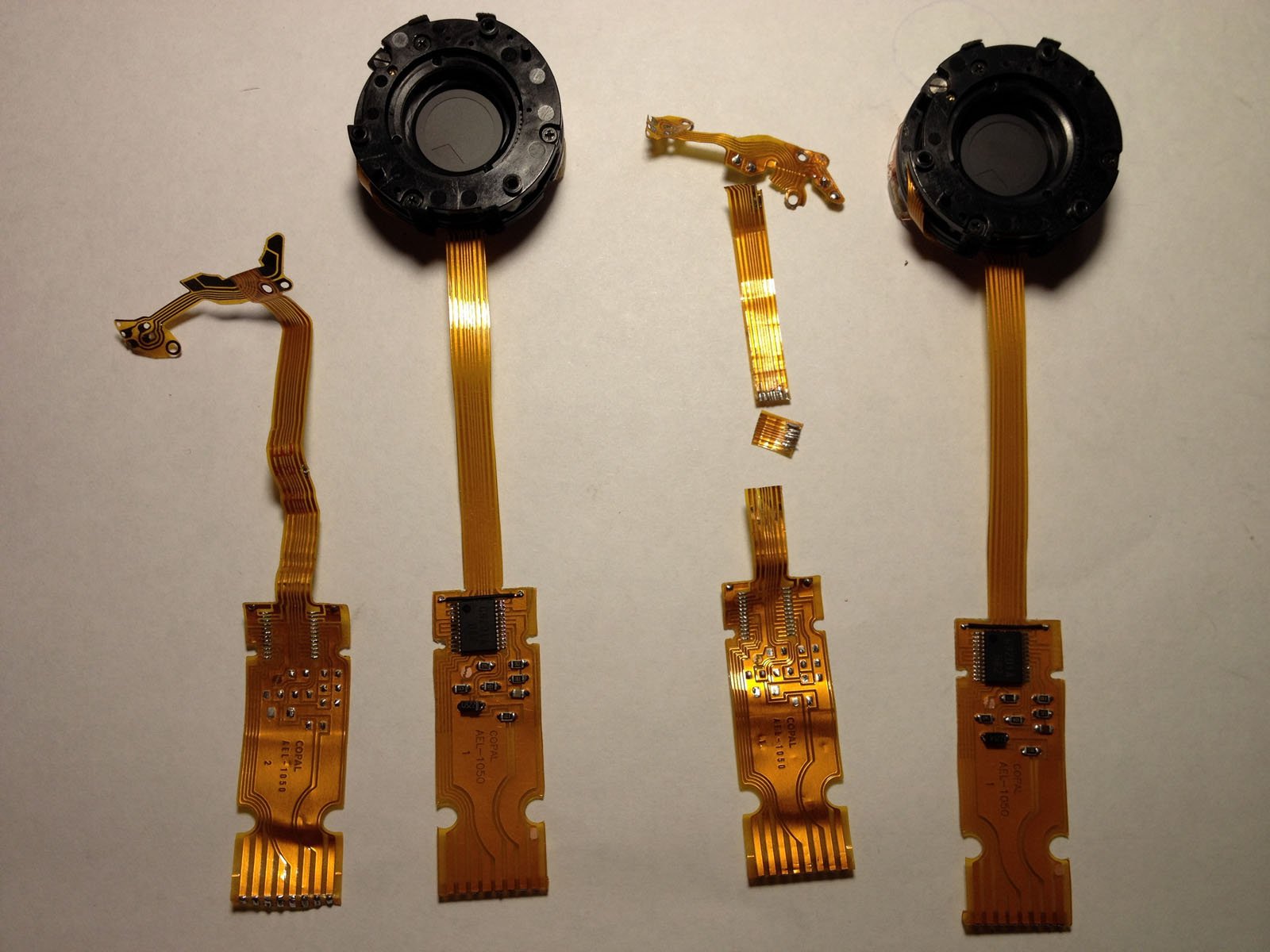

“I told him that I have a Leica Minilux and I bought a flex cable, but I don’t have my own equipment yet,” Gordiychuk tells PetaPixel. “The Man in the Hat” taught Gordiychuk how to solder, how to fix flex cables, and gave him a microscope. “He didn’t deal with cameras, so he couldn’t give me specific advice, but with his explanation, I was able to change the cable in the camera and transfer elements from the old to the new flex cable.”

![]()

![]()

“But this was not enough, because after assembly the shutter still did not work, and after two days I realized that everything is more complicated than just changing the cable — you also need to take into account the phase on the shutter magnet for correct initialization. I even have a video of this moment.”

“This repair was not perfect. I made several mistakes that allowed me in the future to understand why this camera might be faulty after other repairmen who, unlike me, did not succeed in solving these problems,” Gordiychuk explains. He made the final assembly at Zykov’s workshop and made additional Leica Minilux repairs there.

The legendary repairman posted about the fixes that Gordiychuk was successfully doing, and soon enough, people who had broken cameras began to reach out. At the time, only maybe three workshops in the world could repair this specific camera.

Gordiychuk then took some broken cameras to a well-known workshop in Moscow, and the managers gave him a broken Zenit Et to repair for a test. “I immediately saw what was wrong and fixed the camera in front of them with one movement of a screwdriver. After that, they started giving me serious equipment. I worked with them up until my move from Russia. At this stage, I repaired the Mamiya RZ67 and Mamiya 7. I did lens cleaning and lens repair. I could do any adjustments, any cleaning of optics from fungus and haze, I could do cementing of lenses.”

Gordiychuk also worked as an assembly engineer at a well-known augmented reality startup in the automotive industry, where he assembled prototypes and provided notes for improvements.

![]()

Despite failing to meet the requirements for the position and the interview, Gordiychuk impressed the company by investigating some technical drawings they had lying around. He identified design issues, which were tests for leading engineers being interviewed.

“They called me half an hour after I left the building and said they would hire me. This is a good example of how my curiosity and perseverance helped me achieve success,” Gordiychuk says.

After leaving the job at the film lab, his old boss asked Gordiychuk if he could repair his broken Minolta TC-1. “I couldn’t refuse him, but there were no spare parts for this camera.” One of the faulty components was a flex cable, which was impossible to get anywhere.

Gordiychuk learned about a local company, Rezonit, that could fabricate new cables based on custom designs. The company made 18 cables for Gordiychuk on a single A4-sized sheet, and he could then repair these classic cameras. “For me, it was something new, and I realized that I can fix anything if I really want to.”

Shortly after fixing the Minolta, Gordiychuk found Jack Wiegmann on YouTube, and then learned how to fix an old Contax TVS camera.

“Jack Wiegmann is still in my contacts, and I’m grateful to him for his research. He was still a student, and I was amazed that at such a young age, he was able to understand such a complex camera. I believe that he is a more capable person than me because at his age it was simply impossible for me.”

By this point, Gordiychuk had successfully repaired Leica Minilux, Ricoh GR1, Minolta TC-1, Contax TVS, Leica CM, and Ricoh GR21 cameras.

![]()

Branching Out and Repairing More Vintage Cameras

Shortly thereafter, he began repairing the Hasselblad Xpan. “Moscow was generous to me. People trusted me and took the most expensive and most desirable cameras for repair because no one else was doing it. Everyone was afraid of this camera.”

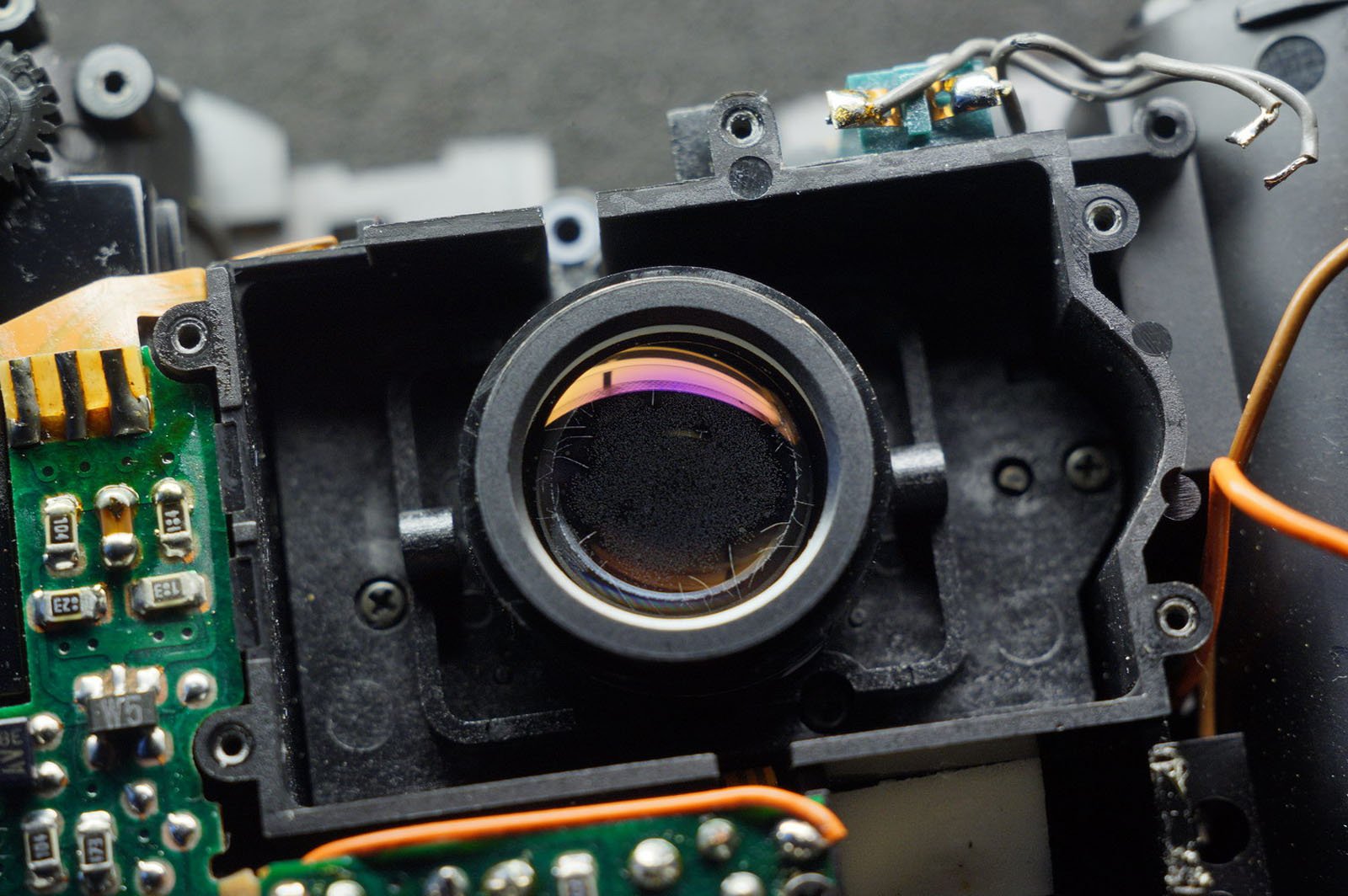

“One day, I wanted to shoot with the Hologon 16/8 for Contax G, so I started buying broken Contax G1 cameras and trying to fix them. They all had different faults, and I was able to fix them all.”

Gordiychuk says, “The very first one, as always, was the most difficult. It was after one well-known workshop that charged too much for repairs, and when they returned the camera, it turned out that all the parts had been replaced with faulty ones.”

He fixed every faulty part and got the camera working again. Everything was broken, including the shutter, autofocus gear, and motherboard. To address the issue with the gears, Gordiychuk asked his colleagues from the startup to produce new gears for him.

![]()

This repair was a significant turning point for Gordiychuk. He had previously been repairing only compact cameras, but now that he could fix Contax G-series cameras, the Hasselblad Xpan, and Konica Hexar cameras, he could now fix broken system cameras.

The Drive to Revive Broken Cameras

“So why am I doing all this? What gives me the motivation to keep searching for a solution during sleepless nights? I like all the cameras I repair.”

“I bought broken cameras that I liked and tried to fix them myself. My main principle was to first repair my own camera, then others. I made all the mistakes on my own cameras. Since I’m a perfectionist, I always tried to make the repair perfect.”

![]()

“This is my main motivation to finish the repair, and I fix every camera as if it were for me, correcting the smallest nuances and trying to make every camera perfect. It was a push for self-development. Now I’m driven more by the desire to repair something that no one else can.”

Gordiychuk says he repairs nearly a camera every day. “I can’t stop. I like it, and I always want to repair something new that other repairmen can’t do.”

These days, he repairs a wide range of cameras including Contax TVS, TVS II, T2, T3, G1, G2 (and all lenses), Contax TLA200, Leica Minilux, Minilux zoom, Leica CM, Minolta TC-1, Ricoh GR1/S/V, GR10 and GR21, Konica Hexar RF, Mamiya 7 (and all lenses), Hasselblad Xpan and Fujifilm TX-1 (and all lenses), and Fuji GA645, GA645W, GA645ZI.

![]()

![]()

“In principle, these are all premium compact and system rangefinder cameras with electronics at the dawn of the film era. I like these cameras myself. I can’t repair cameras I don’t like. I just don’t have the motivation to give them the same care and attention as the ones I like.”

Many of the cameras, given their age, run into issues with normal wear and tear, including broken shutters, flexible cables wearing out, or worn gears in autofocus motors.

The photographer and repairman, who now bounces from place to place due to the Russian invasion of Ukraine, brings people’s beloved old cameras back to life. It is one of the best gifts anyone can give a photographer, as cameras are as precious as they are complicated.

Aleksandr Gordiychuk says he stays plenty busy and, therefore, does not want PetaPixel to link directly to his social media. Still, people who require help should be able to find him easily enough. He keeps a journal of his repairs and has an active YouTube channel.

Image credits: All images courtesy of Aleksandr Gordiychuk