“I have the perfect camera for you,” my dad Tom told me when I said I needed one for my film photography class at Gonzaga University in 2008. “Take my Nikon FTN, it was always my favorite,” he said. “But you can’t keep it. I want it back.”

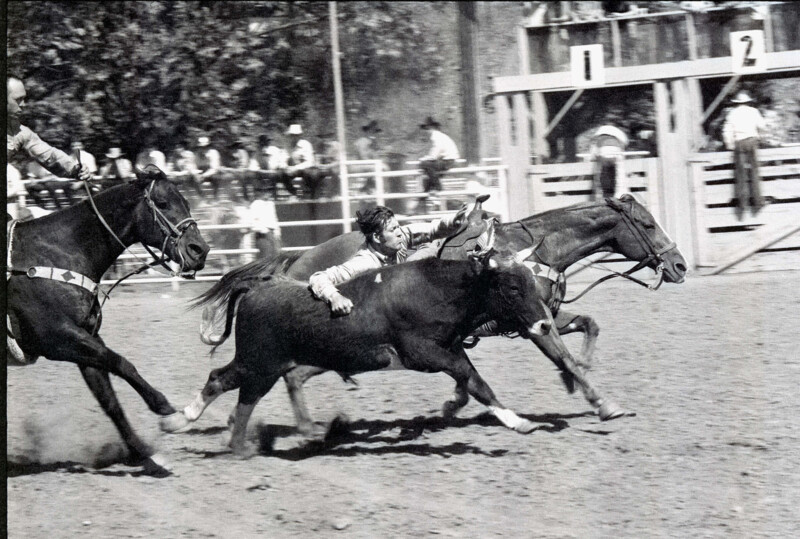

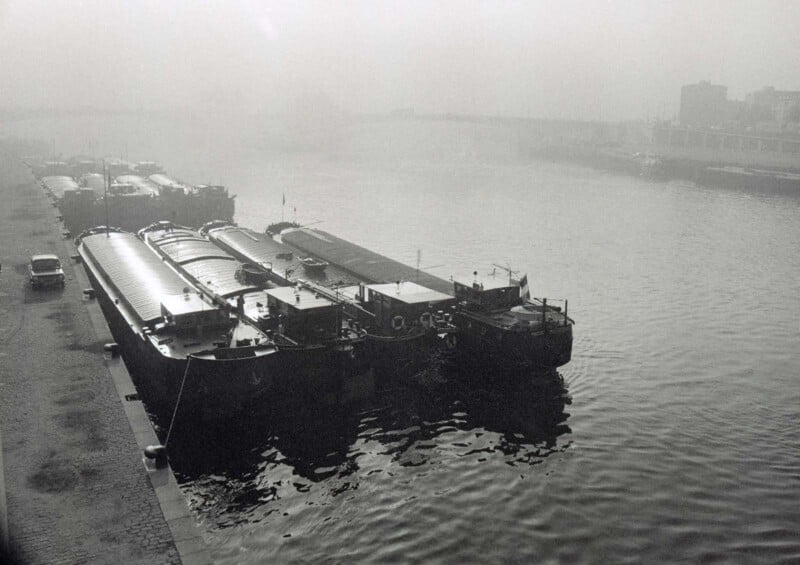

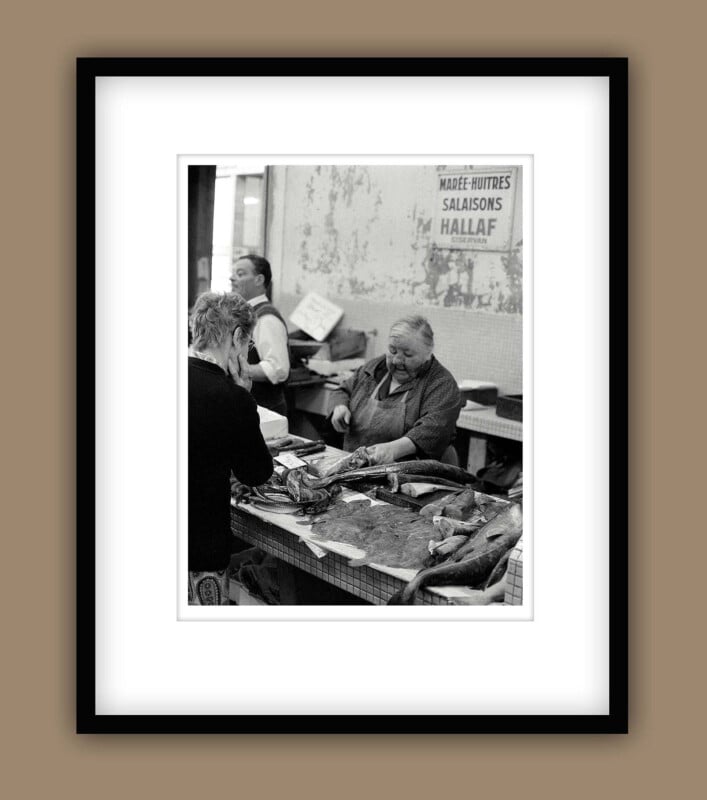

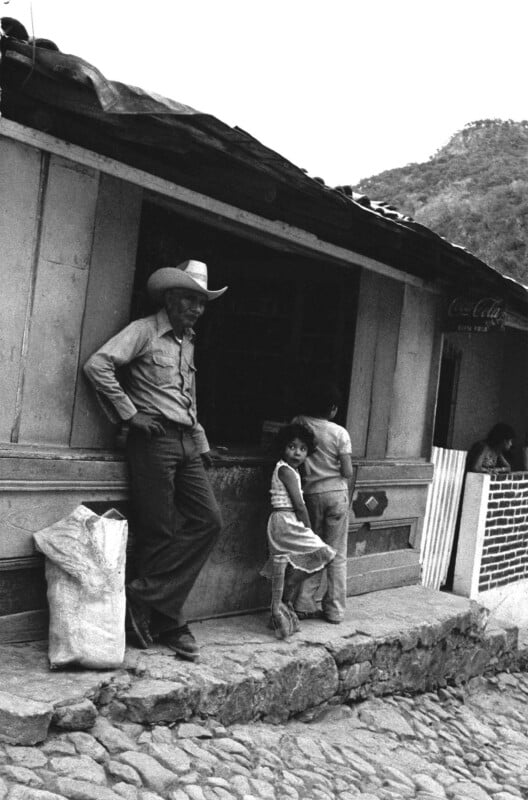

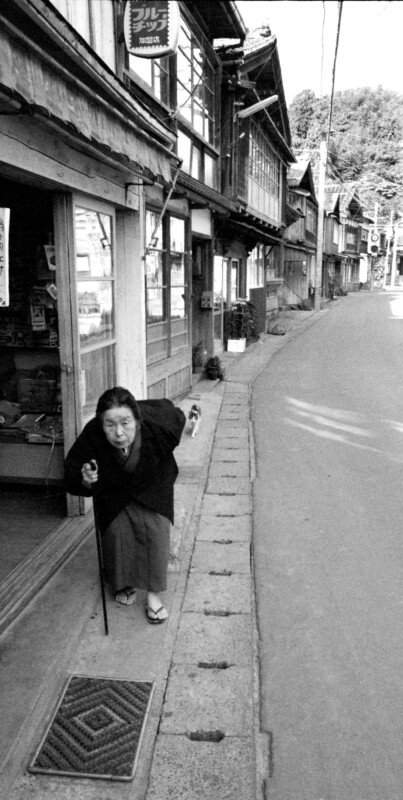

After hundreds of hours with it in my hands combined with time in the darkroom later, I did eventually give it back to him. He wasn’t planning on shooting film again — he had long since switched over to Canon digital — but it was sentimental to him. His best work, both in his mind and mine, was captured with that camera and his Nikon F in the 1960s and 70s in Santa Cruz, California as well as in Italy, France, England, Mexico, and Japan.

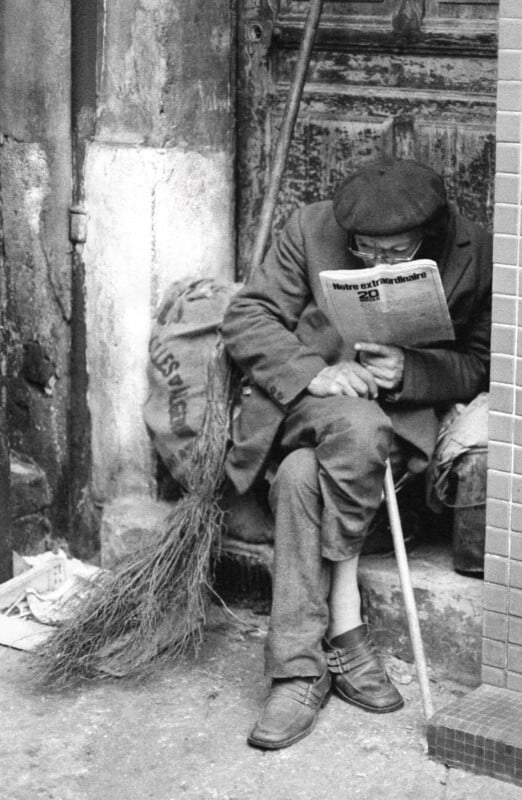

“I have a Bachelor’s Degree in Fine Art and Art History from Stanislaus State University. After graduation in 1968, I was struck by the works of Henri Cartier-Bresson and the rest is history. I haven’t put down my camera since,” my dad wrote in a description of his work.

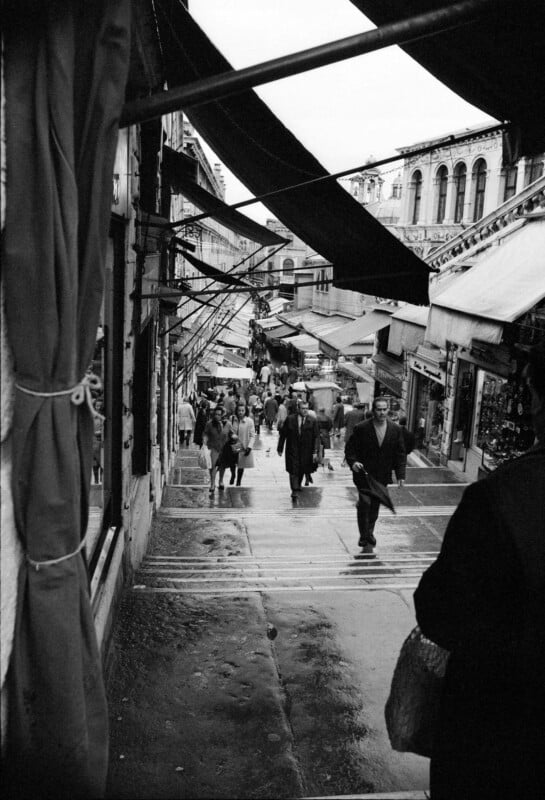

“I spent four years working in hotels in Switzerland and Northern Italy, which gave me the opportunity to submerse myself in local life and culture that resulted in these photographs. I hope you enjoy them.”

This photo was taken in the 1970s and we would, as a family, return in 2009 and stay here, welcomed by the son of the man he used to work for who still owned and operated the hotel.

My dad was a street photographer. He loved capturing real, true moments in public places; the “definitive moment” was something he always chased. His lens of choice was, most commonly, his Nikkor 24mm f/2.8. He developed all of his film himself.

For the next several decades, my dad’s photos stayed as negatives in a folder, tucked away in a box in his office. When I was in high school, he bought a film scanner and asked me to teach him how to use Adobe Photoshop CS6 so that he could start to look over his images and decide what he wanted to do with them.

That process took years. He was raising a kid, after all, and his time to spend in front of his computer — at the desk I’m writing these words from now — was limited. He cared more about spending time with me than his photos, which is a testament to his dedication as a father. But a few years later, he finally had the photos digitized, selections made, and final edits applied.

When he finally retired in the mid-2010s and with me out of the house and on my own, he decided that was the perfect time to do something with his photos. He took his selects to a local printer and then picked up supplies and taught himself how to matte and frame. His high-quality T-square and custom cutting board he used are leaning against the wall behind me now; those who have watched recent episodes of The PetaPixel Podcast will have seen it.

Slow and steady, he carefully selected not only his photos but deliberated how they would appear once matted and then framed. He chose the same simple, black frame for all his prints, but they vary dramatically in size and matting. His smallest measured 19 by 23 inches while his largest was 37 by 25 — he was happy to go larger if requested. He hung them in his house, turning his halls into a literal photo gallery. He also was granted numerous shows and awards locally in Salinas, Monterey, Carmel, and Pacific Grove.

“The object of street photography is to capture the essence of a commonplace moment. In my photos, I try to offer a literal and personal rendering of a subject matter that gives the viewer a more visceral experience of walks of life that might otherwise be only vaguely familiar,” Tom wrote.

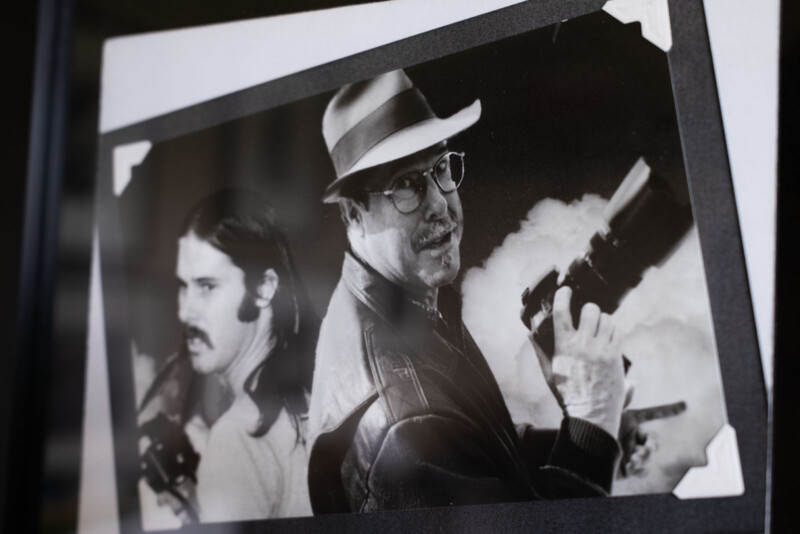

“One’s worldview is affected and influenced by the characters that pass through one’s existence, whether in real life or through their literary and artistic works. Among mine, I would have to include Fra Angelico, Claude Loraine, Camille Carot, Giorgione, Henry Moore, Ernest Hemmingway, F. Scott Fitzgerald, George Orwell, Vladamir Nabokov, Lawrence Durrell, Kurt Vonnegut, Frederick Forsyth, Carles Bronson (for the TV show, Man With a Camera) Michelangelo Antonioni, David Hemmings (for the movie, Blow Up), Randall Kane, and Fergus Whitcraft, as well as the small circle of enduring friends that stretch back to childhood and, of course, family.”

Tom Schneider died last week at home, my mother and I at his side. His love of travel and the outdoors had a cruel side effect that came in the form of an aggressive skin cancer that he spent just shy of a year fighting. It is the only fight I can recall my dad losing.

I learned photography through the same lenses with which my father perfected his art and my love of this profession was strongly backed by his support. I’m a terrible street photographer and have always been in awe of what he was able to capture. His photos taught me about the importance of composition, though, and his appreciation of art in all its forms continues on in me.

While they encapsulate a world left behind, there is a timeless nature to his work (which he must have thought too, since that was the title of his photography showings). His gallery will live on, physically on the walls of my and my mother’s home, and now here.

I love you, dad. Thank you.

“I am often asked what kind of camera I use, as if it’s the camera that is responsible for the end product. My answer is that the camera is merely a tool, a recording device, just as the paintbrush is a tool to the painter or the chisel to the sculptor. It’s after the photo is returned to the dark room or opened in Photoshop that the artistry begins. The ‘art’ is in the creative activity of the artist in the studio. What you see hanging on the wall is the result of art. This is true of any medium.”

-Thomas Albert Schneider (1946-2024)