Con Dempsey, pitcher for the San Francisco Seals, March 17, 1950.

Hearst Newspapers

Minor league prospects who were destined for great things and then flamed out are a dime a dozen. But even by the standards of mid-20th-century barnstormers, San Francisco’s Cornelius “Con” Dempsey had a colorful life and career. He stormed the beaches of Normandy on D-Day and fought in Okinawa. As a baseball player, the 6-foot-4 sidearmer kept crossing paths with the biggest names of the era.

Satchel Paige, “the biggest draw in black baseball,” who brought a championship to Cleveland during his first year in the majors at age 42 (or so), competed against him. Lefty O’Doul, the legendary San Francisco Seals manager known for developing talent for the majors like Joe DiMaggio and bringing baseball to Japan, mentored him. Branch Rickey, who famously signed Jackie Robinson to the Dodgers and broke baseball’s color barrier, may have broken him.

Dempsey’s baseball career might have lasted six short years, but from the time leading up to his pro career through the bitter end, he went through multiple lifetimes’ worth of experiences.

Advertisement

Article continues below this ad

For a man whose life became so interesting, Dempsey’s origins were anything but. Historical documents disagree on when Dempsey, who was raised in an Irish family, was born, placing the date on either Sept. 16, 1923, or Sept. 16, 1922. In his youth, his athletic prowess didn’t emerge right away. The lanky San Franciscan couldn’t even crack his high school team. It wasn’t until he enrolled in the University of San Francisco that he was able to ascend. He got some tips from USF’s coach, and some San Francisco Seals training on campus, and then used that advice to dominate local semi-pro union leagues where pharmacists, waiters and factory workers competed in their spare time.

Con Dempsey of the San Francisco Seals, 1950.

San Francisco Public Library

In 1942, he appeared for the Labor League’s Production Machinists, the Redwood City Merchants, the Seals Stadium Winter League’s Veneto Restaurant, and the Owl Druggists. Normally, noting that someone played working-class stiffs would be a pejorative used in an online argument meant to discredit an older player’s accomplishments. In Dempsey’s case, however, playing against that competition got the attention of the White Sox. Nevertheless, he chose to finish school before going pro.

His stock as a prospect grew further with the USF Dons until 1943 when he, like so many other young men at the time, was called into service for World War II.

Advertisement

Article continues below this ad

“He got some military awards, so he was actually fighting,” Dennis Snelling, a Society for American Baseball Research member, and author of multiple books on the Pacific Coast League, told SFGATE. “There were some ballplayers who played during the war and traveled doing that. He definitely wasn’t one of those.”

Con Dempsey tries to tag out Lloyd Merriman at first base, April 29, 1951.

Newspapers.com

Dempsey was one of very few to fight in both theaters of World War II. His service nearly ended in friendly fire in Japan. Dempsey and three friends took a shortcut back to base after watching a nearby show when they heard shots ring out. The bullets were meant for Dempsey and his friends, as they’d been briefly mistaken for Japanese snipers. The major who frantically ordered his soldiers to hold their fire later told Dempsey, “Your height kept the whole four of you from being shot.”

Advertisement

Article continues below this ad

Dempsey returned home, and to the mound, in a little less than three years as a decorated veteran. Somehow, he looked better than ever. His first game back with the Dons was a 15-strikeout 7-2 win against Santa Clara. A couple of games later, he pitched so well against St. Mary’s that he ruined a star player’s reputation of being a two-sport athlete. By season’s end, he had amassed a 7-1 record with 85 strikeouts, 11 walks and a Northern California collegiate title.

Lefty O’Doul’s San Francisco Seals came calling the following year. Dempsey first had to prove himself for the Pioneer League’s Salt Lake Bees in 1947. He went 16-13 with a 2.95 ERA, but he didn’t think he accomplished enough with those numbers to warrant a return to the Seals. That was until a team owner from a competing minor league continued to bug him about leaving the San Francisco farm system.

“Con got his Irish up and declared: ‘I’m making this team here! ’ He proceeded to do so,” wrote Harry Borba of the San Francisco Examiner in 1949.

Doing so meant getting O’Doul’s famed mentorship on the Seals. The manager helped the towering righty refine certain pitching habits. He taught Dempsey how to drive a batter back from crowding the plate without throwing a wild pitch, and he encouraged the pitcher to start throwing more sidearm pitches. Dempsey sparingly used this motion for curveballs and threw most pitches overhand, which the manager thought looked more effective.

Advertisement

Article continues below this ad

Con Dempsey beats Mel Duezabou to first base, June 24 1951.

Newspapers.com

O’Doul’s magic worked instantly, and it took 33 1/3 innings before Dempsey gave up his first run with the Seals. As for his new habit of throwing a “duster” at a batter every now and again, any malice stayed on the mound. When Dempsey was hit by a pitch while “day-dreaming and scheming” in the batter’s box during a game, for instance, he told reporters, “Honest, it was my fault, not Hafey’s. Why, when he came over to apologize, I apologized right back.”

The retooled Dempsey finished 16-11, with a 2.10 ERA and a league-leading 171 strikeouts in 1948. His impeccable rookie season earned him All-Star appearances during which he competed against Satchel Paige, whom he defeated in a 2-0 shutout, and Jackie Robinson, which resulted in a 7-5 loss. He kept his crown as strikeout king of the PCL the following year when he led the league with 164.

Dempsey would soon be on his way to play some of the most important baseball of his life, and the games would have, as the International News Service reported at the time, “enough color and panoply to make up for all their dismal failures on the coast during last season.”

Advertisement

Article continues below this ad

In the fall of 1949, O’Doul brought Dempsey and 25 other players — many of whom were Seals players — along with two coaches, two club executives, one trainer and 300 Louisville Slugger baseball bats, across the Pacific Ocean to play baseball in Japan for the first time since World War II ended. It was the fifth time O’Doul had made such a trip but the first for everyone else.

Con Dempsey of the San Francisco Seals autographs a baseball at the Sebastopol Boys Club “sports night,” Feb. 9, 1950.

Newspapers.com

The pomp and circumstance was unlike anything Dempsey had ever seen. The Associated Press reported that “tens of thousands of fans lined some five miles of city streets to cheer the visiting Pacific Coast leaguers.” Many waved flags with the team name on them, children begged for autographs, and older fans in the crowd cheered O’Doul’s name.

Dempsey marveled at the crowd, telling a teammate, “The states were never like this.” His teammate retorted, “Yeah. What if we’d won the pennant?”

Advertisement

Article continues below this ad

Dempsey pitched well in exhibition games against Japanese all-stars and even caught a ceremonial first pitch from Jean MacArthur, the wife of General Douglas MacArthur. The man who oversaw the American post-war occupation of Japan would go on to call the trip “the greatest piece of diplomacy ever.” A couple of months after their return to the States, O’Doul declared Dempsey would be the most sought-after minor leaguer.

It became immediately clear that O’Doul’s big prediction about Dempsey wasn’t exactly going to pass. He finished the 1950 season with a 4.36 ERA and 100 strikeouts. A sports writer who used to cover him in Salt Lake even noticed during the season that Dempsey had a “strange problem” with his control. The San Francisco Chronicle reached out to Dempsey’s former USF coach Pete Newell to see what was wrong with him, but Newell didn’t feel comfortable giving his assessment.

“Gosh, I don’t want to encroach on Frank O’Doul’s territory,” Newell said in 1950.

The pitcher finished the season with a mediocre 9-9 record mostly from the bullpen — far from O’Doul’s prediction of a 20-win season.

Advertisement

Article continues below this ad

Con Dempsey holds a pigeon at his pens, Jan. 30, 1949.

Newspapers.com

O’Doul also predicted Dempsey’s value at about $100,000, which was closer to reality. The Pirates, who had been interested in the pitcher for years, finally purchased Dempsey conditionally for $75,000 with a literal 30-day return policy.

This should have been a well-deserved call-up to the majors, and a vital turning point for Dempsey’s career. Instead, by the pitcher’s own account, it torpedoed his career.

Pittsburgh asked him to move on from the sidearm throwing motion that put him on the national radar and shift to only throwing overhand. Dempsey originally attributed this to Bucs manager Billy Meyer, though later it became commonly accepted that Branch Rickey, Pittsburgh’s general manager at the time, made that call. A San Mateo County Times reporter once claimed that Rickey went as far as to throw out the box score of an exhibition game that Dempsey won because of his sidearm pitches.

Advertisement

Article continues below this ad

“Dempsey was acquired before Branch Rickey took over the Pirates, so Rickey didn’t have a vested interest in Dempsey,” Snelling told SFGATE. “It wasn’t his guy. I’ve seen stories that say Rickey wanted him to start throwing overhand instead of sidearm. I don’t see a reference to that; that doesn’t mean it didn’t happen, because Rickey would do something like that.”

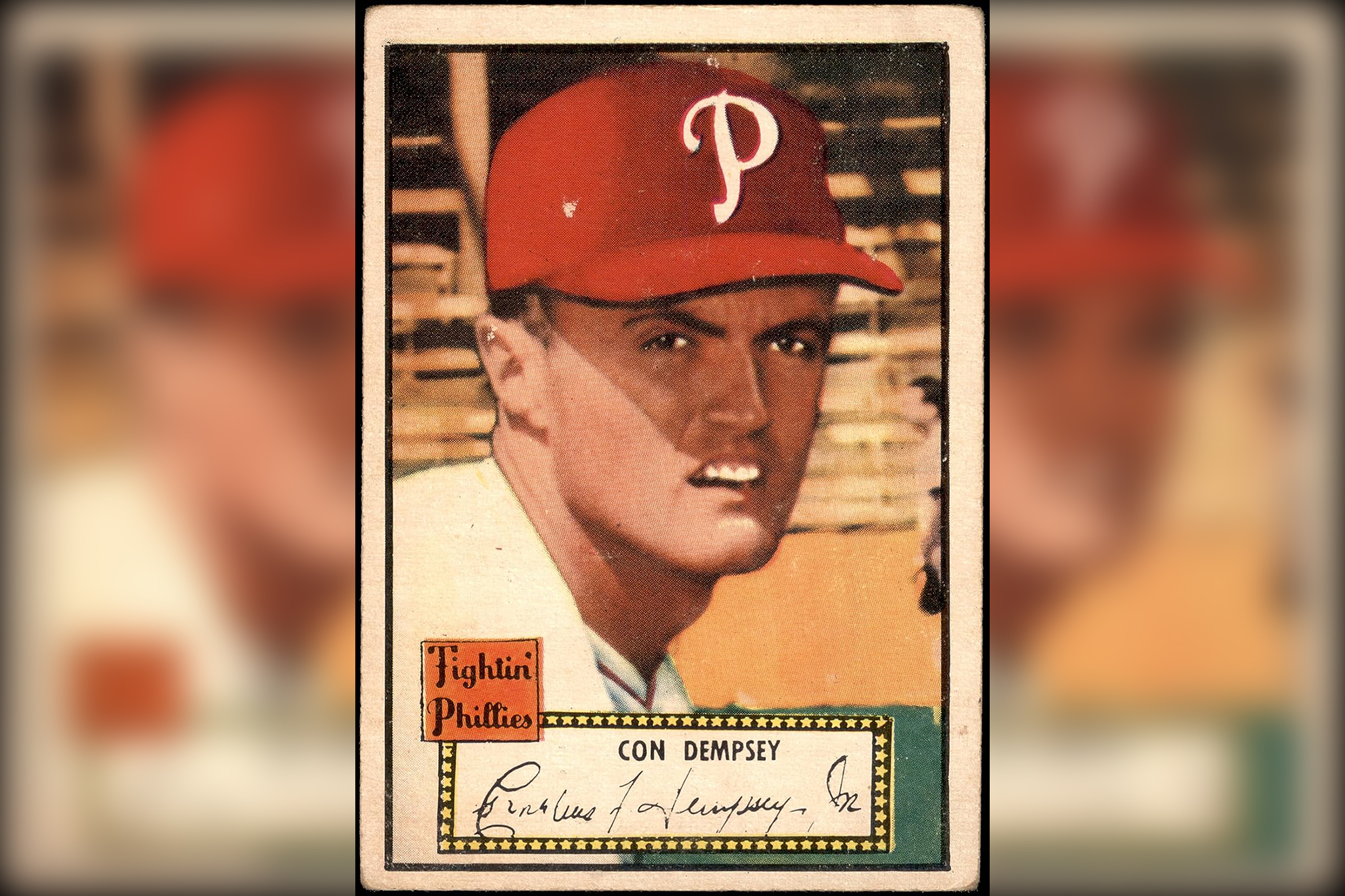

Baseball card of Con Demsey.

Screenshot via Amazon

It wasn’t enough that his time in the majors was a failed experiment lasting seven innings over three games in eight days. (He’d later say, “I kept my luggage packed” about his cup of coffee in the big time.) The Pirates broke him. Pittsburgh ended up cashing in that return policy, and the Seals never got their full $75,000 from the Bucs. To add insult to injury, Rickey didn’t even tell San Francisco that Dempsey was coming back. The team found out through the Chronicle.

“That’s typical of the way Rickey operates,” Seals general manager Joe Orengo told the paper at the time.

Advertisement

Article continues below this ad

The Phillies drafted him after the 1951 season for $10,000 and sold him to the Seattle Rainiers in late April 1952 after he was offered back to the Seals, who didn’t want him. When he got to Seattle, Dempsey was diagnosed with bursitis in his arm and couldn’t pitch for the season, likely from the ill-fated advice that Pittsburgh gave him.

He took 1952 off and attempted a comeback with the Oakland Oaks in 1953. Team president Brick Laws approved the signing after seeing Dempsey pitch three exhibition innings, but Dempsey was released in August 1953. He finished with a 4-10 record, 5.18 ERA and 62 strikeouts. It was the last real stat line of his career.

Dempsey’s life story didn’t end on the sour note that his baseball career did. After getting a master’s degree from USF, he turned that experience into a job as a gym teacher and coach. In 1954, Dempsey started a 34-year teaching career at A.P. Giannini Middle School. His children described him as “caring” in a 2006 story following his death, noting that he “strived to be the best” and loved racing pigeons.

Con Dempsey (upper left) listens in as Clyde McCullough argues with umpire Lou Jorda, April 29, 1951.

Newspapers.com

Advertisement

Article continues below this ad

He didn’t leave everything from his baseball career behind when he moved to teaching. In 1957, the school showed the 1951 film “Angels in the Outfield,” which featured some Pirates players on the roster at the time. Students screeched “That’s Mr. Dempsey!” when they saw their teacher, according to the Chronicle.

That wasn’t the first time his teaching adventures were documented in the paper. Less than one year after hanging up his cleats for the last time, he suffered a comically timed accident.

“SAN FRANCISCO — AP — Con Dempsey, former Pittsburgh Pirate and San Francisco Seal hurler, told his junior high school physical education class: ‘Knowing how to jump and how to fall is important.’

“Then he stepped back, tripped over a mat, fell and broke his arm.”

Advertisement

Article continues below this ad

At least he couldn’t blame Branch Rickey for that one.