Maybe it was the wordless image of the U.S. Olympic hockey team celebrating the “Miracle on Ice.” Perhaps it was the perfect frame of Dwight Clark making “The Catch” to send the San Francisco 49ers to the 1982 Super Bowl. Or it could have been the declaration that a 17-year-old LeBron James was “The Chosen One,” 20 months before he played in his first NBA game.

For sports fans of a certain age, the memory of running to the mailbox to see what was on the cover of the latest weekly issue of Sports Illustrated is indelible. For decades, the magazine’s photographers, writers and editors held the power to anoint stars and deliver the definitive account of the biggest moments in sports, often with just a single photograph and a few words on the cover. It was the most powerful real estate in sports journalism.

“When I was a kid and getting SI, you didn’t have that immediate 24-hour news cycle just hitting you over the head,” said Nate Gordon, a former picture editor at Sports Illustrated who is now the head of content at The Players’ Tribune. “You would get that cover and you’d be like: ‘Man, this is what happened last week. That’s so cool.’”

To the extent any magazine had that power, it is severely diminished now. But the road has been particularly rough for Sports Illustrated, with its shrinking staff and reduced print frequency. Last week, most of the employees were either laid off or told their employment would be uncertain after 90 days, leaving the publication’s future in flux.

Sports Illustrated’s power to define sports discourse faded long before 2024, however. A combination of factors such as growth of sports across cable channels, the presence of more team-controlled media and the ascendancy of the internet had been steadily eroding the influence of the magazine and its cover for years. But it is hard to overstate the power it once had.

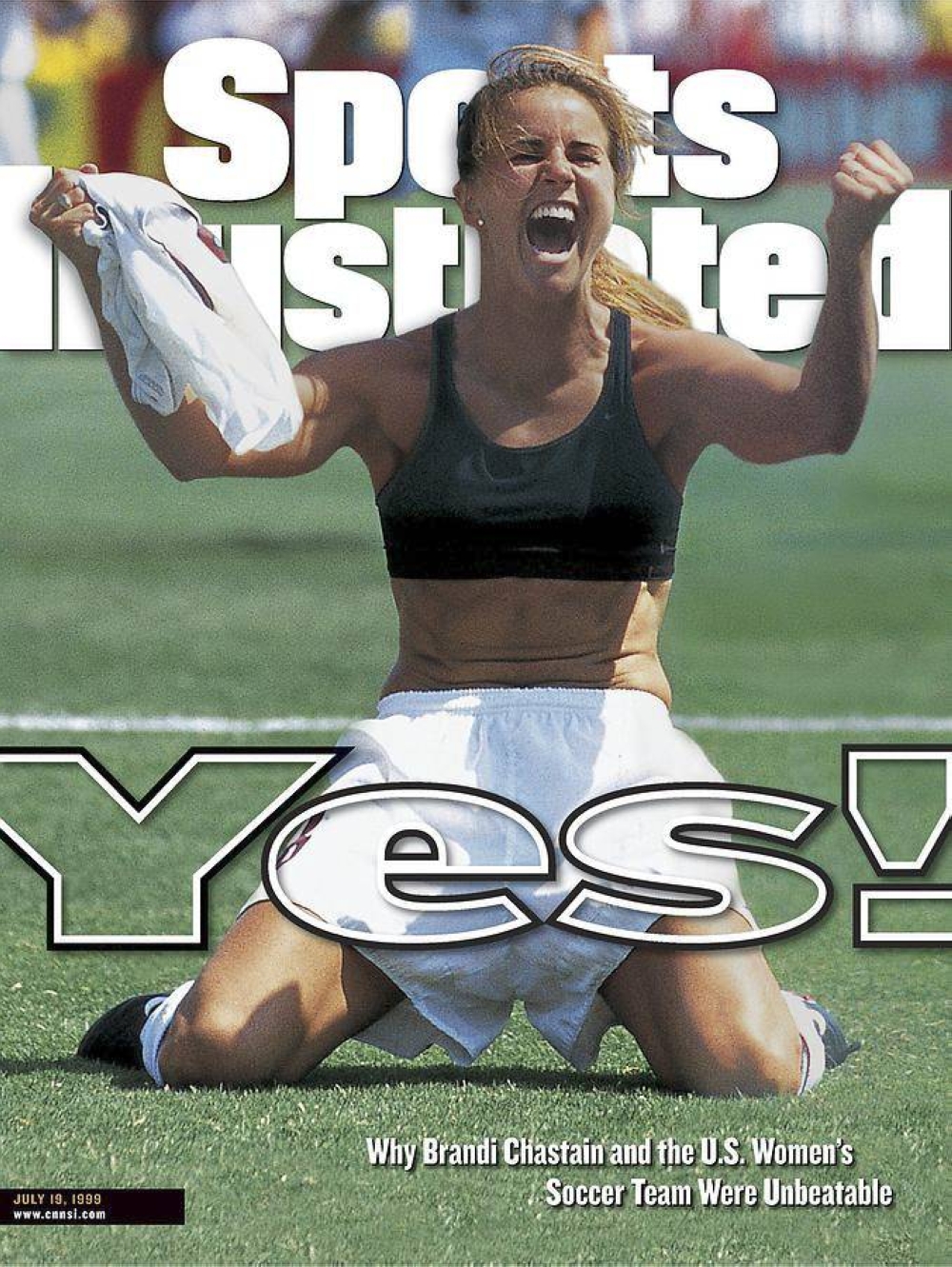

Robert Beck was one of the last remaining Sports Illustrated photographers when the magazine laid off all of its photojournalists in 2015. He is best known for his head-on photograph of a sports-bra-wearing Brandi Chastain celebrating the U.S. soccer team’s victory in a penalty shootout in the 1999 Women’s World Cup final.

Dozens of photographers were at the match, and Beck was far from the only one who took a picture of Chastain’s celebration — though unlike others, he captured her image head on, rather than from an angle. It was the photograph’s placement on the Sports Illustrated cover that made it famous.

“As far as Joe Normal knows, he thinks Robert Beck got the only picture of that,” Beck said.

Famed athletes such as Muhammad Ali, Michael Jordan and Tiger Woods have each appeared on the magazine’s cover dozens of times. For Fred Vuich, one image of Woods stands out.

Vuich was on his first assignment for Sports Illustrated at the 2001 Masters. Stationed at the 16th hole for Sunday’s final round, he thought he would get a shot of Woods sewing up his fourth straight major, the Tiger Slam, with a birdie. But Woods missed the birdie putt, and Vuich did not have enough time to get to the distant 18th green.

Instead, using a silent camera with no motor to avoid disturbing Woods’ backswing, Vuich took a wide shot from a tower of his tee shot at the final hole, nearly surrounded by fans. Sports Illustrated’s editors put it on the cover, along with one word: “Masterpiece.”

“That picture made my career,” Vuich said, pointing out similarities in its composition to the cover photograph of Sports Illustrated’s first issue, in 1954, which showed Milwaukee Braves third baseman Eddie Mathews, small in the frame at home plate in a crowded stadium.

In addition to capturing classic moments, Sports Illustrated could introduce athletes to the wider world. James was still in high school when he first appeared on the cover in 2002.

“The cover pushed me onto the national stage, whether I was ready for it or not,” he said in a book published in 2009 with journalist Buzz Bissinger.

Superstar athletes, both well before and after James appeared on the cover, would clamor for a spot and promise photographers and writers hours of their time. Sports Illustrated’s influence was such that its annual swimsuit issue helped fuel the rise of supermodels such as Kathy Ireland, Tyra Banks and Brooklyn Decker. But with great power comes great responsibility — and one superstar never forgave the magazine after he felt it treated him unfairly on its cover.

Jordan has not granted interviews to Sports Illustrated’s writers for three decades, after a cover told him to “Bag It, Michael” and called his short-lived baseball career “embarrassing.” Steve Wulf, who wrote the accompanying article but did not write the cover line, has been apologizing for it ever since.

Other athletes had more complicated relationships with Sports Illustrated’s cover. In 1989, the magazine put Michigan State’s Tony Mandarich on the cover and called him “the best offensive line prospect ever,” shortly before he was taken second in the NFL draft.

Mandarich recalled in a 2009 autobiography seeing 50 copies of the magazine on the newsstand at Los Angeles International Airport. “I recognized then that I was an item for the national press, big time national press,” he wrote. “That was another heady experience, fueling my arrogance and sense of superiority.”

Three years later, as he was flaming out of the league, Sports Illustrated declared Mandarich “The NFL’s Incredible Bust.” In his autobiography, Mandarich admits that it was accurate, but said he “felt the emotional swift kick in my gut that I believe Sports Illustrated intended when they published it.” He would boycott Sports Illustrated’s reporters for 12 years.

Some were also spooked by the so-called Sports Illustrated cover jinx, which was said to inflict injuries or poor play on those who graced the cover. The jinx itself once made the cover — featuring a photograph of a black cat — and was the subject of a long article exploring whether it was real.

Over the years, as the economics of publishing changed, so did the cover selection.

“It became less of a news thing and more of a personality thing,” said Al Tielemans, a staff photographer for almost 20 years. He described an evolution of editors wanting the key moment of the game, and then a good photo of the star of the game, and then a photo featuring the most famous person in the game, and then finally just a headshot of a star.

Last year, perhaps in a bid for celebrity buzz, and possibly as a result of the longer lead time needed to print the magazine, Sports Illustrated named Deion Sanders its Sportsperson of the Year. At one point his Colorado Buffaloes, in his first years as their coach, were 3-0 and No. 18 in the college football rankings. But by the time the magazine with Sanders on the cover came out, the Buffaloes were 4-8.

The internet, and social media platforms such as Instagram, mean that more photography is showcased to more people than ever before. Now that fans see every angle of every game, with highlights and shots available instantly on social media, no single image has the same power that Sports Illustrated’s cover once did.

In 2014, Tielemans shot a memorable cover of a 13-year-old girl, Mo’ne Davis, pitching at the Little League World Series. He dreamed of having a 20- or 30-year career as a photographer at Sports Illustrated, which he achieved. But he hoped he would eventually be replaced by a new generation of photographers, shooting their own famous covers.

Instead, when he was laid off in 2015, he was not replaced at all.

This article originally appeared in The New York Times

© 2024 The New York Times Company