Women are more likely than men to have their immune system turn against them, resulting in an array of so-called autoimmune diseases, like lupus and multiple sclerosis. A study published Thursday offers an explanation rooted in the X chromosome. The research, published in the journal Cell, suggests that a special set of molecules that act on the extra X chromosome carried by women can sometimes confuse the immune system.

Experts said the molecules are unlikely to be the sole reason autoimmune disease skews female. But if the results hold up in more experiments, it may be possible to base new treatments on these molecules, rather than on current drugs that blunt the entire immune system. “Maybe that’s a better strategy,” Dr. Howard Chang, a geneticist and dermatologist at Stanford who led the study, said.

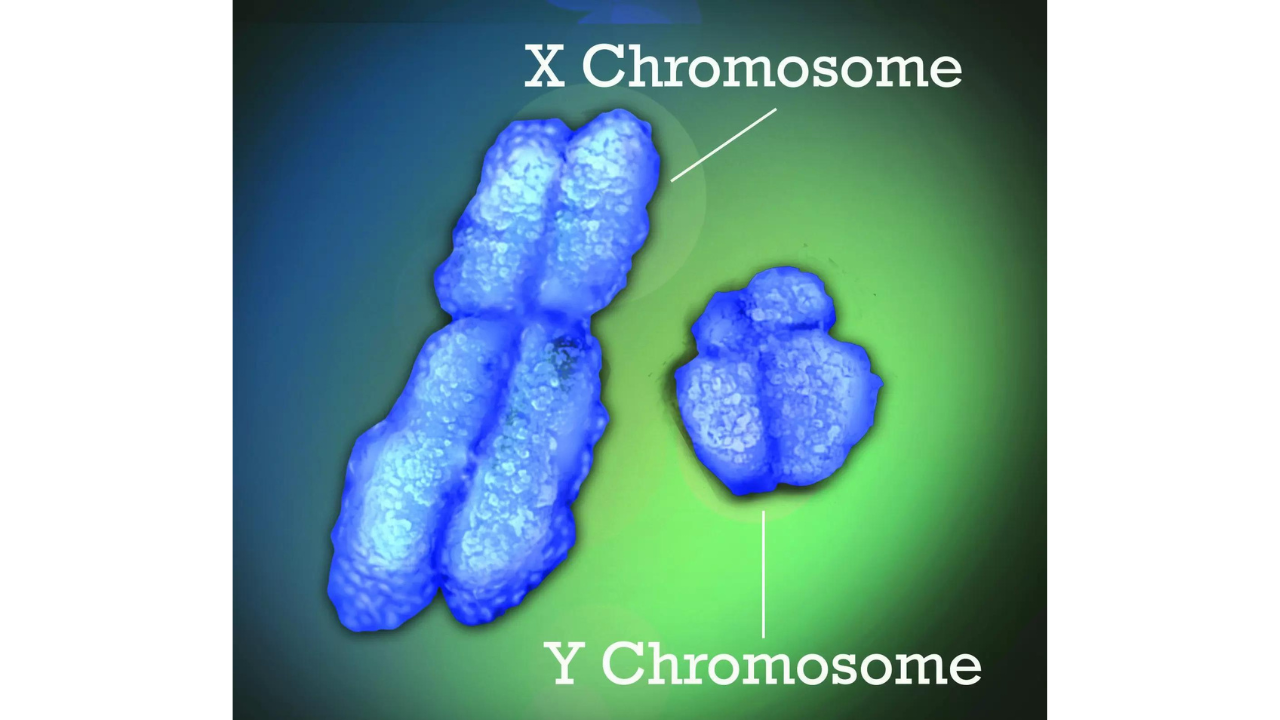

Male and female embryos carry 22 identical pairs of chromosomes. The 23rd is different: Females carry two Xs, while males carry an X and a Y, which lead to development of male sex organs. Each chromosome holds genes that, when “switched on,” produce proteins to do work inside cells. You might expect that women, with two copies of X, make twice as many X proteins as men do. Instead, they produce about the same level. That’s because one of the two chromosomes is silenced.

A molecule called Xist clings to the second X chromosome “like Velcro,” Chang said. As hundreds of Xist molecules wrap themselves around the X chromosome, they shut it down. In 2015, it occurred to Chang that the silencing itself might also have a downside.

Chang suspects autoimmune diseases may come about during the normal process of cells dying in a woman’s body. The cells spill open, dumping their molecules into the bloodstream. In women, that debris includes Xist molecules and the proteins attached to them. When an immune cell encounters an Xist molecule, it also finds the proteins stuck to it. This unusual experience may confuse immune cells, which then mistakenly start making antibodies to the Xist proteins. Once the immune system starts treating Xist proteins as the enemy, it may start attacking other parts of the body as well. That’s because every cell sticks fragments of its proteins on its surface, where immune cells can inspect them. If an immune cell encounters an Xist protein fragment, Chang says, it will kill the cell that presents it.

The challenge now is in figuring out how all these factors work collectively to produce the female bias in diseases.

Experts said the molecules are unlikely to be the sole reason autoimmune disease skews female. But if the results hold up in more experiments, it may be possible to base new treatments on these molecules, rather than on current drugs that blunt the entire immune system. “Maybe that’s a better strategy,” Dr. Howard Chang, a geneticist and dermatologist at Stanford who led the study, said.

Male and female embryos carry 22 identical pairs of chromosomes. The 23rd is different: Females carry two Xs, while males carry an X and a Y, which lead to development of male sex organs. Each chromosome holds genes that, when “switched on,” produce proteins to do work inside cells. You might expect that women, with two copies of X, make twice as many X proteins as men do. Instead, they produce about the same level. That’s because one of the two chromosomes is silenced.

A molecule called Xist clings to the second X chromosome “like Velcro,” Chang said. As hundreds of Xist molecules wrap themselves around the X chromosome, they shut it down. In 2015, it occurred to Chang that the silencing itself might also have a downside.

Chang suspects autoimmune diseases may come about during the normal process of cells dying in a woman’s body. The cells spill open, dumping their molecules into the bloodstream. In women, that debris includes Xist molecules and the proteins attached to them. When an immune cell encounters an Xist molecule, it also finds the proteins stuck to it. This unusual experience may confuse immune cells, which then mistakenly start making antibodies to the Xist proteins. Once the immune system starts treating Xist proteins as the enemy, it may start attacking other parts of the body as well. That’s because every cell sticks fragments of its proteins on its surface, where immune cells can inspect them. If an immune cell encounters an Xist protein fragment, Chang says, it will kill the cell that presents it.

The challenge now is in figuring out how all these factors work collectively to produce the female bias in diseases.

Denial of responsibility! Swift Telecast is an automatic aggregator of the all world’s media. In each content, the hyperlink to the primary source is specified. All trademarks belong to their rightful owners, all materials to their authors. If you are the owner of the content and do not want us to publish your materials, please contact us by email – swifttelecast.com. The content will be deleted within 24 hours.