On Oct. 23, publisher Sanseido did what it would usually do for an upcoming title: It uploaded the basic details of the book, along with sample pages, to its website. It then issued a press release for it, the Otaku Yogo Jiten Daigenkai, or Otaku Dictionary Daigenkai, compiled by students of Nagoya College and headed by Japanese literature researcher Yoshiko Koide.

By that afternoon, netizens were up in arms.

“There is not even a bare-minimum level of correctness that a publicly published book should have,” said one X user in a post that has been viewed 10,000 times. Another posted, “Publishing such subjective, dōjinshi (self-published magazine)-quality work and calling it a ‘dictionary’ is just going to decrease the credibility of Sanseido so they should really stop.”

How did a so-called dictionary for “nerds” come to cause so much uproar?

Sitting in a pristine white-boarded seminar room on campus, 40 minutes by train from Nagoya Station, Koide cuts a slim figure in a billowy black dress. With her sweet and melodic cadence, the 41-year-old hardly seems like the figure at the center of such an internet firestorm, yet, as she says, “That’s the power of words.”

Koide is a doctoral graduate of Nagoya University Graduate School of Humanities, and her dissertation was on grammar in the “Manyoshu,” the oldest known anthology of poetry in Japanese. The students of her Japanese-language observation seminar at Nagoya College, a private women’s junior college, weren’t quite champing at the bit to discuss eighth-century particles, however, and indeed Koide found them largely quiet and unresponsive during lessons. Yet when she met with them outside of class, she found they couldn’t stop talking — about things far from her world: Splatoon, K-pop, boys’ love.

Could she find a way to channel their extracurricular enthusiasm?

In 2022, Koide had her class of five women compile what would become an “otaku dictionary.” The students picked their own topics to include in the book and used their subjective experiences and uses of the language as material.

“When linguists go out to study local dialects, they meet the dialect speakers and record what they hear; instead, here it is as if the dialect speakers wrote the book themselves (about their language),” says Koide.

At the end of the year, the students self-published their “dictionary” and sold it at the college festival. It was such a success that Koide repeated the project with her 2023 class, and after Sanseido approached the school, the two volumes came together to be Otaku Dictionary Daigenkai, which hit shelves across Japan this past Tuesday.

Entry points

The book comprises 14 chapters chosen by the students, including games (Arknights, Pokemon) and idol culture (K-pop, Japanese boy idols), as well as general usage terms. There’s a chapter on BL, short for “boys’ love” or “yaoi,” stories centered around male gay couples, as well as 2.5 dimension, musicals in which real-life people act out two-dimensional media, like anime.

Koide refers to herself as a “karui otaku,” or “light otaku,” saying that she’s been into novels and manga since her student days. When asked which ones, she looks bashful and laughs, declining to answer.

But many of the otaku worlds inhabited by her students, especially in gaming and K-pop, she says, were new to her.

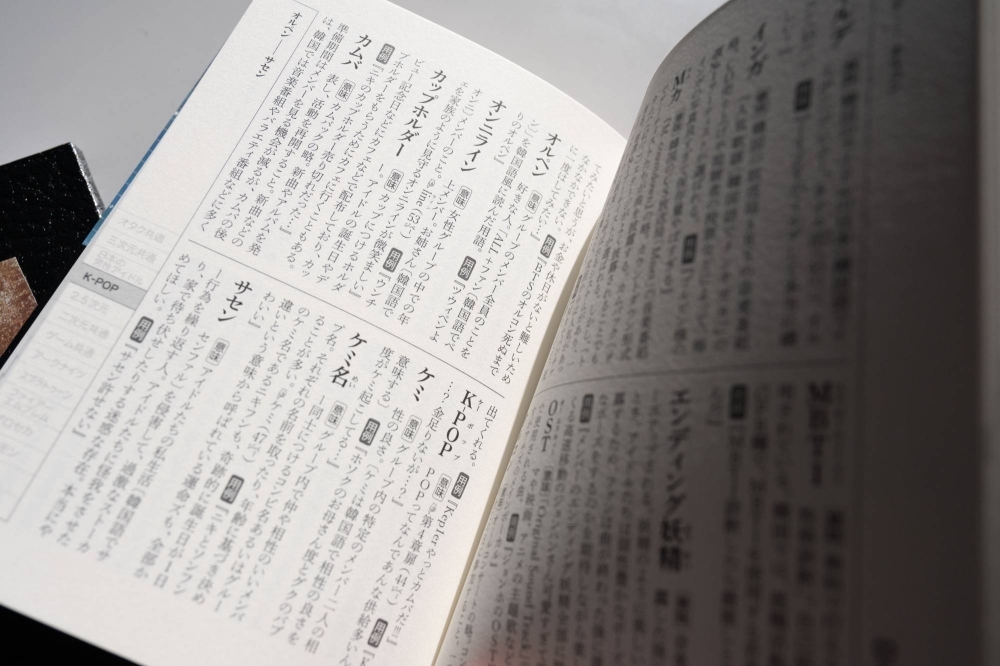

The pages of the Otaku Dictionary Daigenkai are divided into chapters that cater to different areas of otaku fandom.

| TAIDGH BARRON

She recalls hearing the term “同担拒否” (dōtankyohi) for the first time and being totally in the dark.

Indeed this concept requires some otaku-style linguistic gymnastics. “Dōtankyohi” combines “tantō,” which literally means “to be in charge of,” and in otaku speak signifies someone (a celebrity, or idol, for example) a fan wants to support because they feel they have a responsibility for the person to succeed. “Dō,” literally the word for “the same,” as in “at the same time,” combines with “tantō,” to signify a person with whom a fan shares this obsessive responsibility. And finally “kyohi” means rejection or refusal.

In other words, “dōtankyohi” is used when you don’t want to share your fandom; your love object is for you and you alone.

Another word that surprised Koide was “メタ読み” (meta yomi), defined as anticipating the plot development of a story judging by its structure, background information and characteristics of past works by the same author, without actually immersing yourself in the world of the story.

“It was something I had always done but I was surprised to find (otaku had) a word for it,” she says.

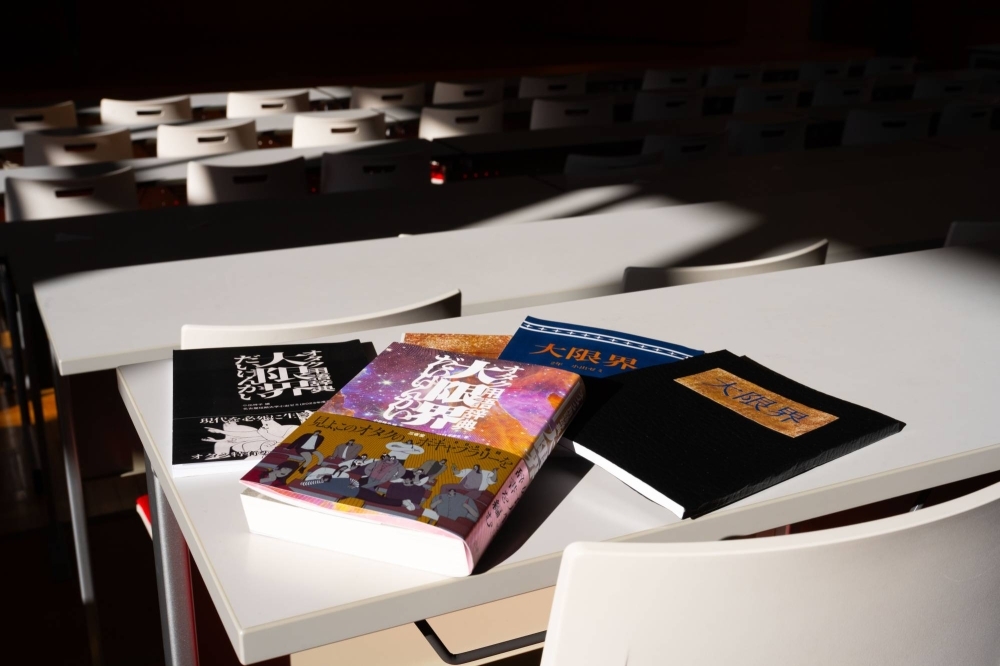

The Otaku Dictionary Daigenkai and some of its reference materials sit on a desk in a classroom at Nagoya College.

| TAIDGH BARRON

She was also surprised to find some words from her own youth still going strong, like “神” (kami) — the direct translation of “god” — which is still used as a term to describe a person or a character who is so impressive it’s hard to believe they’re human.

Elsewhere, words made comebacks in unexpected ways. Koide noticed language from older generations had taken on otaku-specific meanings even though they had faded from general use. The word “タテ” (tate), for example, was a term used in sports reporting to convey how many times in a row a team had won or lost — 3タテ (san-tate) therefore meant having won or lost three times in a row.

Though once familiar to baseball fans, the term would befuddle most young people today — except, perhaps, for avid Pokemon players. To them, “san-tate” means having three of their pokemons destroyed by a single opponent.

Overall, Koide noticed a trend: The words seemed to spread visually — not orally, as you might expect of, say, regional slang. Instead of “I haven’t heard that word,” students would often say “I haven’t seen that word,” Koide explains. Further, they might say, “I haven’t seen it because I don’t use TikTok,” indicating that the lexicon seems to live primarily within social media platforms and not in real-life interactions between otaku friends.

Indeed, a few entries are unpronounceable — like “!!!,” an abbreviation used among fans for the song “More! Jump! More!” from the game Hatsune Miku: Colorful Stage!, also known as Proseka.

A problematic pairing

Koide’s intention was not to create an authoritative reference dictionary of all words used by all otaku, but rather to capture the students’ genuine interests and usage and to help them observe their own relationship with the Japanese language. In her eyes, the book is a commemoration of the work of her two classes.

But the internet didn’t see it that way.

The sample pages that were uploaded to the web included the term “顔カプ” (kao kapu), a portmanteau of “kao” (face) and “kapu” (an abbreviation of “couple” or “coupling”). It means romantically matching — “shipping,” as the kids say — two fictional characters based off of how they look visually together, despite not having much of a connection in the story.

The many stores of Nakano Broadway in Tokyo cater to the country’s various otaku.

| TAIDGH BARRON

In the example sentence included with the entry, the students used an existing “kao kapu” between the male characters Yuji Itadori and Toji Fushiguro from the manga and anime series “Jujutsu Kaisen.” A few fans on social media were not happy — and by a few, we mean thousands. One critical post on X has been liked more than 5,200 times and viewed over 1 million.

Some fans were upset that this fan-invented couple had been exposed. In their eyes, this made public to a wide audience the private passion of a small corner of the internet and thus violated one of the unspoken rules of the fandom.

Others disagreed with the definition itself, arguing that “kao kapu” has a negative connotation, and criticized the publisher for putting out something so “biased” in the eyes of some fans. A few went further, questioning why Sanseido — an established publisher known for its dictionaries — published a student-made otaku dictionary to begin with.

In response to the controversy, Sanseido released a statement on its website that says, “Although we have received criticisms from people who have read our sample pages, we have no intention to demean or insult any groups of people.”

Trading cards for sale in Tokyo’s Shin-Okubo area, also known as the capital’s Koreatown.

| TAIDGH BARRON

The publisher and students decided to amend the entry’s example sentence to refer to a generic “A and B” coupling, but they also took the more drastic response of removing the participating students’ names from the project altogether. Only Koide remains credited.

“On one hand, I was thankful that people were pointing out specific rules and taboos that exist within the fandoms,” one student, who asked not to be named, writes via email. “But I felt it was unfair how we were attacked and degraded for reasons like ‘it’s because it’s made by female college students’ or ‘because the college is considered by certain metrics to be a low-level school’ or because ‘it didn’t align with what I liked.’”

Another student writes, “I was terrified that strangers (on the internet) were saying that they were going to ‘identify who we were.’ I got scared to give my personal information in the book given the possibility that someone might actually come and cause us harm.”

Men stand outside a rack of manga at a store in Tokyo’s Nakano Broadway.

| TAIDGH BARRON

The students and Koide saw their original project as an entirely fan-based, ground-up, self-published document for and by genuine otaku. But once Sanseido got involved, the calculation changed. The act of mass distributing the book across the country — and selling copies for ¥1,400 each — by one of Japan’s biggest dictionary and textbook publishers shifts the platform and intent considerably. When they see the term “dictionary” in the title, fans don’t see a commemorative book of two student seminars, but rather a corporate attempt to enforce gatekeeping and add a sheen of authority to what is really the subjective experience of only a dozen young women.

The power of words

The internet and social media have drastically changed our image of the classic otaku — a nerd with poor social skills and perhaps poorer hygiene, obsessed with a childish hobby. The anonymity of online interactions has granted a sense of agency and community to people who had previously felt isolated and powerless. And today fandoms and online communities more generally can irreparably turn the tides of the publishing industry, Hollywood — and even our democracies.

Otaku culture has also gone mainstream. Otaku are powerful because they can organize quickly, and also because they spend money — and they can combine these to their advantage. If the otaku individual was once to be pitied, today the otaku group is to be feared.

Koide believes the reaction to the book has been so strong precisely because its subject matter is otaku communities and culture.

“People feel (words are) tied to their very beings,” she says, “and especially when it comes to otaku words, they are very tied to the thing you love, and very tied to you as an individual.” When otaku see words “defined” differently from how they use them, she continues, “It feels as if a part of you is being rejected.”

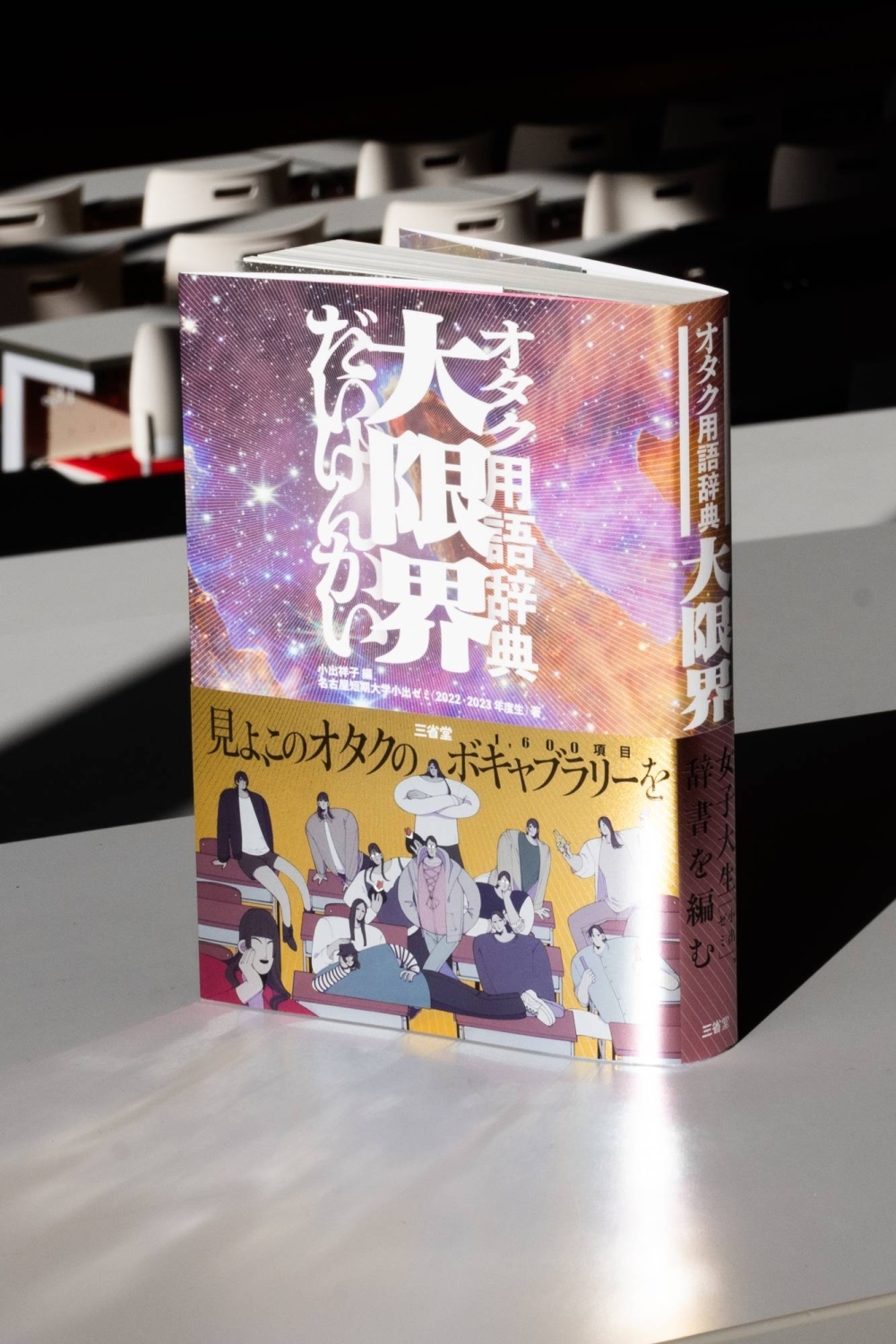

The Otaku Yogo Jiten Daigenkai, known colloquially as the Otaku Dictionary.

| TAIDGH BARRON

Indeed, the self-identifying otaku seem to occupy entire worlds created by unique slang. Koide recounts that her students didn’t need to try very hard to come up with their vocabulary lists — rather, “the words came gushing out of them.” Koide was particularly impressed by the speed at which recalling one word would beget new related lingo, and how the women would scroll through their messaging apps to study their own linguistic behavior.

Working on the dictionary has helped the researcher understand the language of the young people around her better — including her middle school-aged daughter, an otaku of YouTuber group QuizKnock and animated boy band Strawberry Prince.

“Adults like to say things like, ‘Young people these days don’t have a strong vocabulary’ — but they do,” she says. “I myself realized that they have their own unique language that adults just don’t understand, and I want readers (of this book) to feel that, too.”