New Delhi: The Maternal Mortality Ratio (MMR) in India fell precipitously by 82.5 percent between 1990 and 2020, significantly outpacing global improvements in this key healthcare indicator.

The Maternal Mortality Ratio is defined as the number of maternal deaths per 1 lakh live births within a specific period and is considered a key metric to gauge the state of healthcare. Any maternal death that happens immediately or within 42 days of termination of pregnancy, whether through childbirth, abortion, or miscarriage, is counted within the purview of MMR.

An analysis by ThePrint of MMR data from UNICEF, the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare (India), the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA), and the Institute of Economic Growth (India) shows that India’s MMR in 1990 was 556 as compared to the global level of 386.

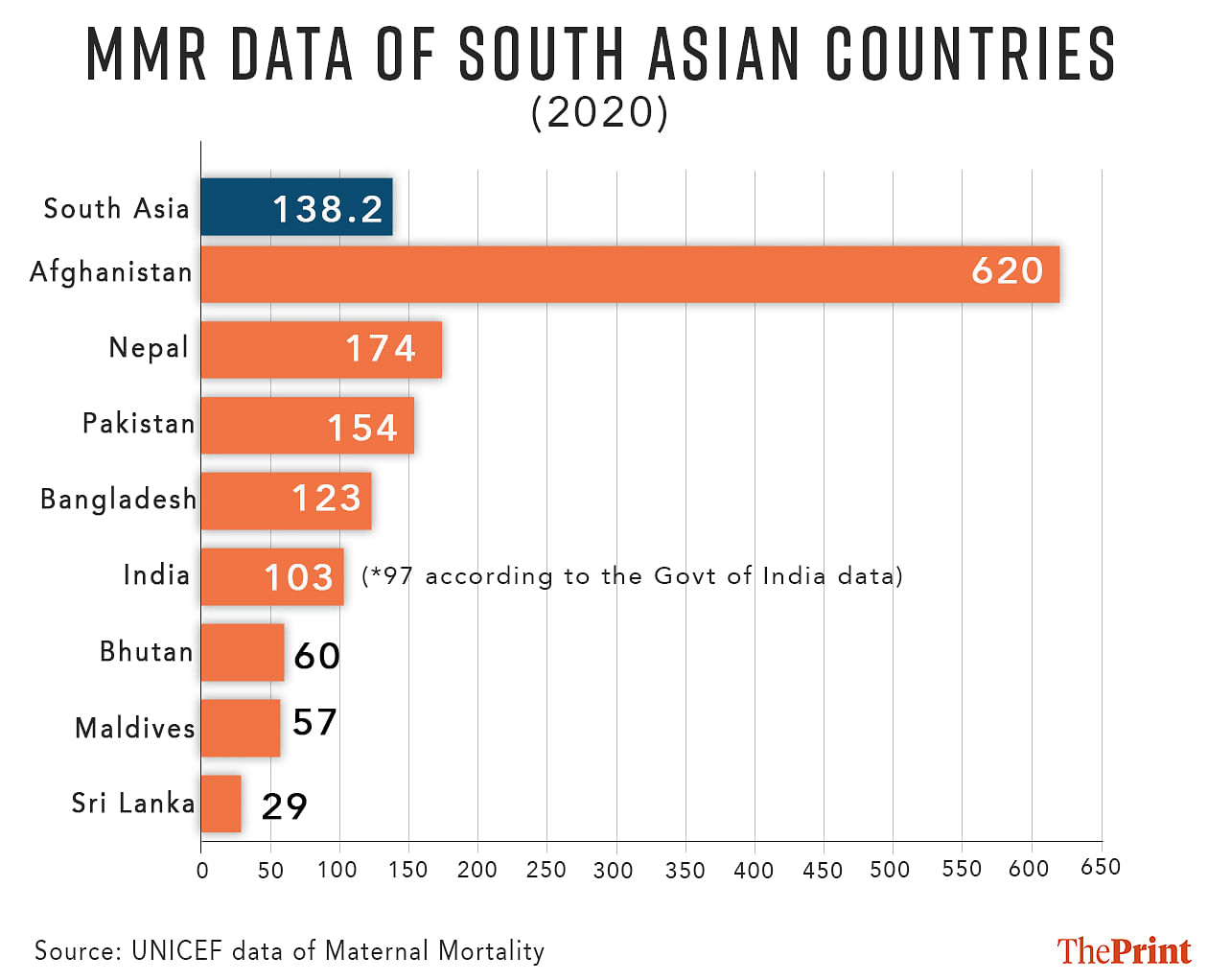

Data from the Union health ministry, UNFPA and the Institute of Economic Growth shows this number fell to 97 in 2020 — the last year for which data is available. UNICEF, however, puts this number at 103, which is still significantly lower than the global level of 223.

Dr Subha Sri B. of CommonHealth — a multi-state non-government coalition working on reproductive health and safe abortion — attributes India’s improvement in this metric to an increase in the number of institutional births, improved emergency transportation facilities, and a greater focus on the quality of healthcare for mothers.

“There are two to three major changes that have led to the decline in MMR. There has been the introduction of programmes like Janani Suraksha Yojana (JSY) to encourage more institutional deliveries. However, without an improvement in the quality of care, these only have a limited impact,” she said. Launched in 2005, the JSY is a centrally-sponsored safe motherhood intervention scheme that integrates cash assistance with delivery and post-delivery care.

Despite India’s progress, its MMR is still lower than the target mentioned in the Sustainable Development Goals — a collection of 17 objectives designed to serve as a “shared blueprint for peace and prosperity for people and the planet, now and into the future”. According to Target 3.1 of the SDGs, the aim is to reduce the global maternal mortality ratio to less than 70 per 100,000 live births by 2030.

Still, India’s progress is better than most other South Asian countries — according to UNICEF data, the MMR is lower than the combined figure for South Asia, which stood at 138. Only three South Asian countries — Bhutan (60), Maldives (57), and Sri Lanka (29) — are doing better than India in terms of the metric.

Also read: House panel pulls up govt over lack of separate maternal mortality database for tribals

Government push

The drop in India’s MMR comes on the back of targeted government efforts. The National Health Policy (NHP) of 2017 aimed to bring down India’s MMR to below 100/lakh live births by 2020 — a target that, going by the government’s numbers, has now been achieved.

The government also has several maternity benefit programmes — including the POSHAN Abhiyaan, a mother and child nutrition programme; the Surakshit Matritva Aashwasan (SUMAN) for affordable and quality healthcare to pregnant women and newborns; Pradhan Mantri Matru Vandana Yojana (PMMVY), a cash benefit programme for pregnant and lactating women; and Labour Room & Quality Improvement Initiative (LaQshya), a scheme aimed at providing quality care intrapartum and postpartum.

Of these, SUMAN and LaQshya schemes have been built on the progress of existing programmes like Janani Shishu Suraksha Karyakram (JSSK) and the JSY. Launched in 2011, the JSSK entitles all pregnant women to free delivery in public health institutions.

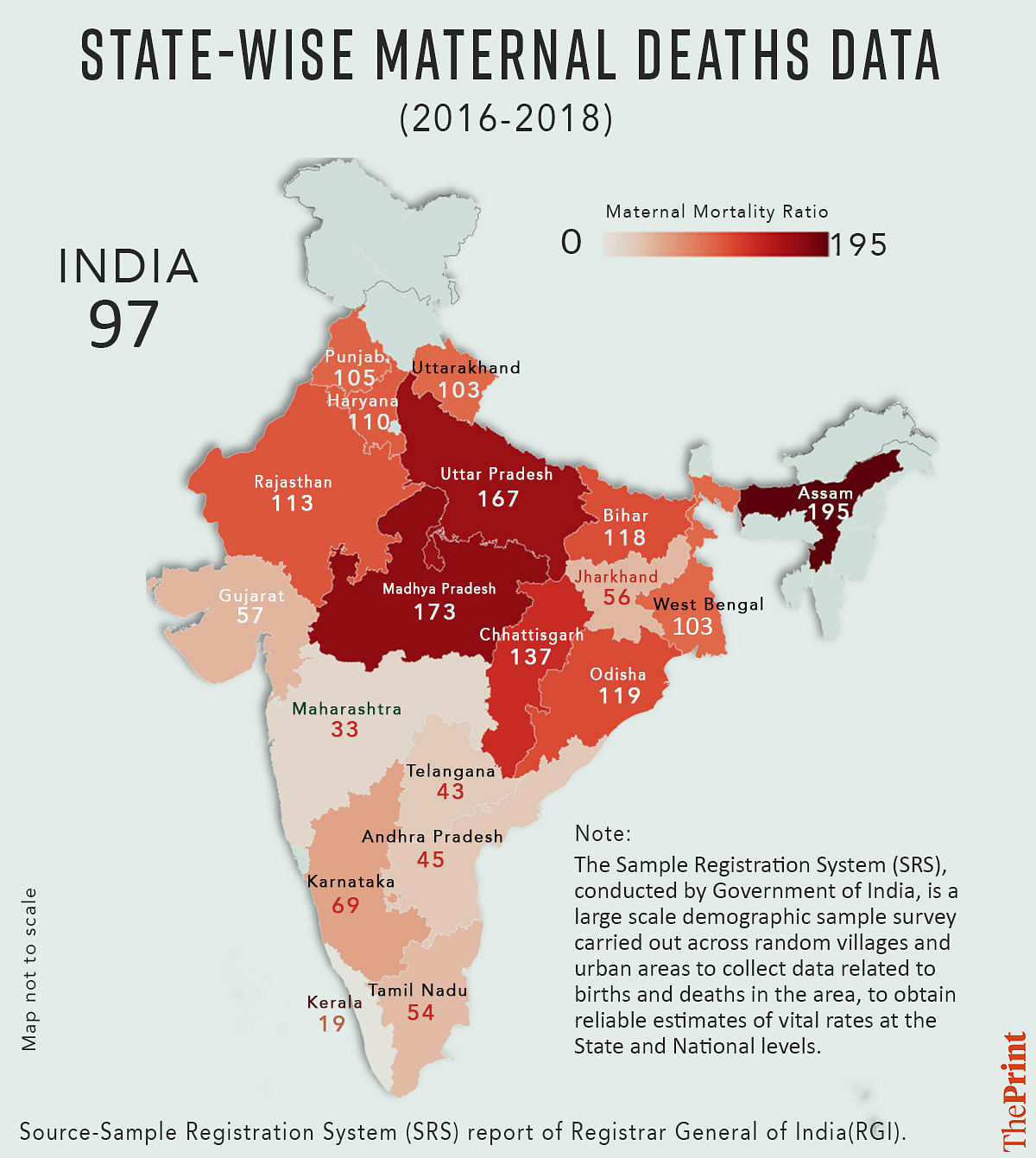

Although India still has to achieve the SDG target of 70 deaths per 1 lakh live births, some states have successfully managed to keep numbers below this.

According to Sample Registration System (SRS) report of 2020 — the Indian government’s large-scale demographic sample survey — these include Kerala (19), Maharashtra (33), Telangana (43) Andhra Pradesh (45), Tamil Nadu (54), Jharkhand (56), Gujarat (57), and Karnataka (69).

However, states like Assam, Madhya Pradesh, and Uttar Pradesh still show MMR over 150.

According to Dr Subha Sri, this disparity can be attributed to factors like existing health infrastructure, poverty, general nutritional levels, and other social and economic determinants.

“States that have historically been lagging in health indicators are likely to have a higher MMR,” she told ThePrint.

Causes of MMR: Lack of healthcare, poverty

According to Subha Sri, while a lack of access to quality healthcare services — particularly in rural and remote areas — is one of the primary contributors to high maternal mortality in India, socio-economic factors like poverty, lack of education, and gender disparities also play a role.

Additionally, early marriages and adolescent pregnancies are still prevalent in some regions of India, increasing the risk of maternal mortality, she said.

“To reach the SDG target, it is important to first identify areas and communities where higher maternal deaths are happening and deploy specific measures to curb this. The second is there has been a greater focus on (the) quality of care for mothers and increased accountability from the health institutions,” she said, adding that apart from direct causes, indirect ones such as high anemia rates, diabetes, and other non-communicable diseases should be addressed.

“Abortion services should be made available widely in the public health system, so deaths due to unsafe abortions do not happen,” she told ThePrint.

(Edited by Uttara Ramaswamy)

Also Read: Eye on 2030 target on neonatal mortality, ICMR to study possible interventions to lower newborn deaths