Fourth-year university student Aruha Hamamura begins and ends most days on his surfboard at Kounohama Beach along the coast of Mie Prefecture’s Shima Peninsula, an area known for the Grand Shrines of Ise and the ama freedivers who ply the nearby waters in search of ocean creatures including the region’s famed pearl oysters.

When not surfing or studying, he works part-time as a barista at a coffee stand in CO Blue Center, a beachside complex that also houses a sauna, an ecologically oriented library and information clearinghouse, a marine agri-tech company and spaces for art exhibitions, satellite offices and co-working. Hamamura lauds CO Blue for its flexible working conditions, but he was also drawn to the center by its eco-friendly ethos of addressing problems such as ocean plastics, deforestation and the looming food crisis.

One initiative that particularly excites him is Re:COIN, a program that upcycles plastic beach trash into “coins,” which can then be redeemed at nearby businesses. The more beach trash you bring to CO Blue, the more coins you can get in return.

Besides addressing problems of seaside waste, Re:COIN aims to deepen community ties and provide a boost to the local economy. Known in Japanese as chi’iki tsūka (local or community currencies), numerous initiatives of this kind have been implemented across the country in recent decades, and CO Blue’s version embodies the spirit of these earlier ventures upon whose shoulders it sits.

Ende’s philosophies

A longtime proponent of addressing issues at the intersection of the economy and ecology is writer Kai Sawyer, founder of the Tokyo Urban Permaculture movement. Sawyer and his family live in Isumi, Chiba Prefecture, at the Peace and Permaculture Dojo, his name for the 150-year-old thatched-roof kominka home and its surrounding grounds. In 2016, Isumi residents implemented a community currency known as the “mai” — using the kanji character for rice — in an effort to encourage transactions that would prioritize relationships of trust and overall community benefit.

“Local currencies circulate community resources by strengthening healthy relationships among people and with the surrounding nature,” Sawyer says, adding that such currencies need not be antithetical to the central economy. “But since people might not understand money and how it works, it feels empowering to create a local currency wherein resources are cycled to go where the needs are. That is what a truly healthy economy does.”

For historical context, Sawyer points to a 1999 NHK documentary, titled “Ende no Yuigon,” that introduced the philosophies of Michael Ende, a German writer who critiqued the capitalist mantra “time is money” in his 1973 novel “Momo.” The documentary also explored the ethical aspects of the mainstream monetary system by questioning the way the market economy divides communities through competition rather than promoting trust and cooperation.

Kai Sawyer, founder of Tokyo Urban Permaculture, speaks in front of his mandala garden during a weekend workshop in spring 2023 held on the grounds of his Peace and Permaculture Dojo in Isumi, Chiba Prefecture.

| KIMBERLY HUGHES

Sawyer says that while Japan is historically no stranger to community currencies, it experienced a boom in such initiatives following the NHK broadcast, citing examples such as the “ma-yu” in Ueda, Nagano Prefecture, whose name means “cocoon” and is rooted in the area’s history as a center of the silkworm industry.

Human connections

Japan’s first community currency appeared in 1973, when Teruko Mizushima established the Volunteer Labor Bank in Osaka. Mizushima envisioned community members helping one another through service, with the VLB’s unit of exchange being the number of hours spent engaged in labor. This spawned numerous other systems that in turn paved the way for the Sawayaka Welfare Foundation’s fureai kippu (literally, “human connection tickets”) in 1995, issued primarily in exchange for elderly, disabled and child care work, whereby credits were either kept for one’s own use or transferred to others in need.

This initiative was followed by a nonprofit organization known as the Eco-Money Network, created in 1999 by Toshiharu Kato, director of the Ministry of Trade and Industry’s Service Industries Division. The network encouraged local regions to meet their specific needs through services provided via community currencies, and by 2003 there were around 35 such systems nationwide. A study published in 2020 noted a total of 792 different community currencies historically, which peaked in 2002 at 130 programs before sliding into descent. These researchers grouped the programs by type into 13 different categories, many of which, like CO Blue’s Re:COIN, were intended to address multiple social issues at once.

The CO Blue Center complex, fronting Kounohama Beach in Mie Prefecture spearheads multipronged social initiatives including a local currency called Re:COIN.

| KIMBERLY HUGHES

Researchers have noted the considerable diversity of Japan’s community currencies in terms of both scale and content, which has made the task of classifying them significantly challenging. Kenichi Kurita, an economics professor at Tokyo Keizai University, says “there is no correct classification, and each viewpoint offers valuable insights.”

Kurita organizes the history of Japan’s regional currencies into four separate sequential phases: “eco-money” used exclusively for volunteering and mutual assistance; community currencies used for commercial transactions in shops, thereby providing local economic stimulation; additional community currency types whose objectives lay beyond the economy, such as education, environmental conservation or fostering connections among residents in rural areas; and digital local currencies aimed primarily toward economic revitalization.

Cultivating the slow life in Kokubunji

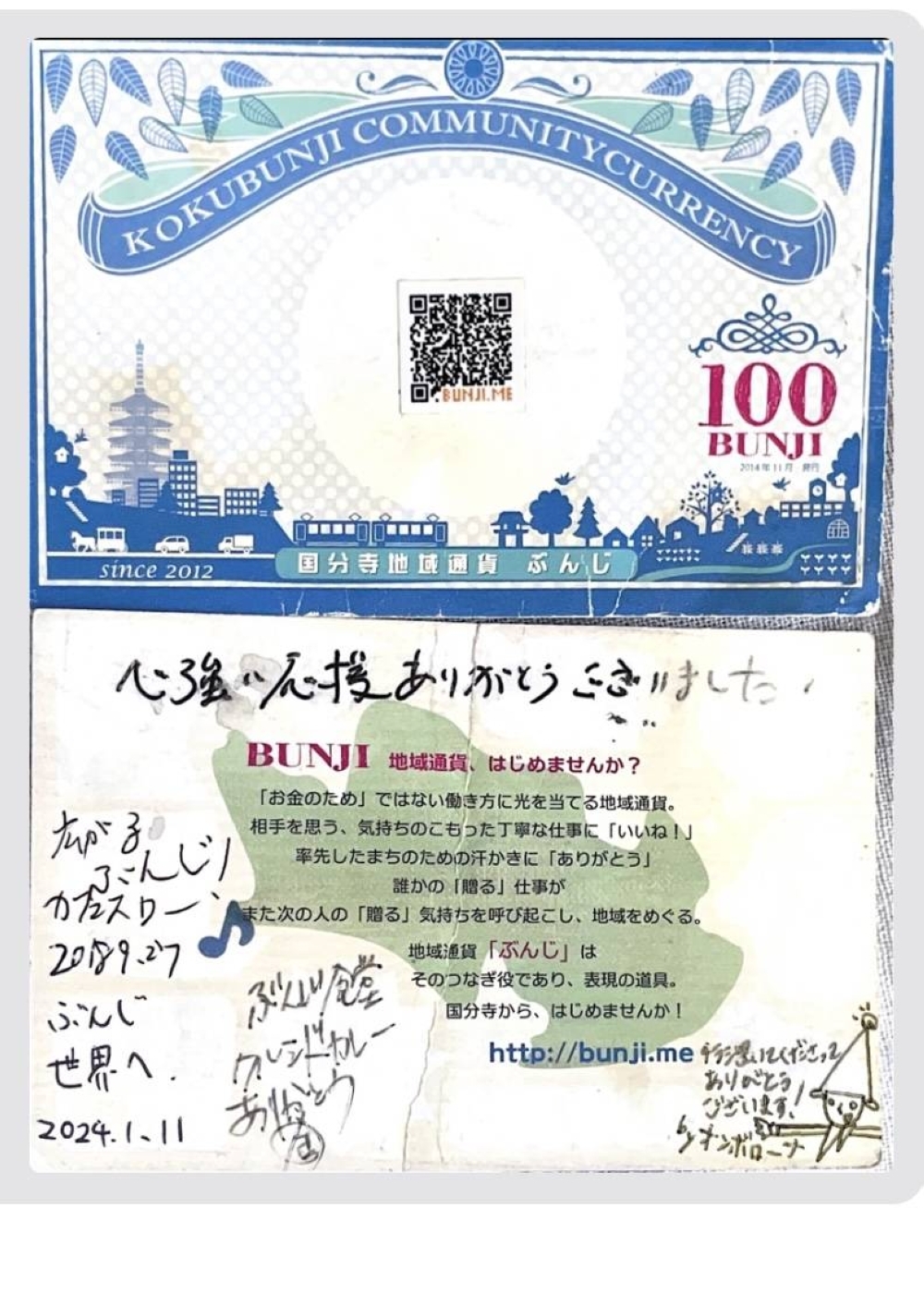

When asked to name a particularly interesting community currency system amid the numerous existing projects, Kurita points close to home: the west Tokyo suburb of Kokubunji, where his university is located and whose local currency is known as the “bunji.” Launched in 2012, the system comprises small notes around the size of a business card that are earned for providing services or attending community events. Bunji notes may be redeemed — or received in lieu of change — when shopping at a partnering business.

You might use bunji to pay for a meal at a participating cafe, for example, which then uses them to purchase vegetables from a local farmer. That farm could then use the notes to pay its volunteers, who in turn use them at another local restaurant or shop. A unique feature of the bunji system is that users are encouraged to write messages on the back of the notes, which might say something like “That was a delicious cup of coffee” or “Thank you so much for your hard work.”

The “bunji” is a unique local currency in Kokubunji, in west Tokyo, whose users pen messages on the back of the notes to help foster deeper community connections. Messages on the note pictured here include expressions of gratitude for service where the currency was spent.

| KIMBERLY HUGHES

As the currency circulates through the community, it helps to cultivate the program’s stated goal of imparting a more personalized flavor to business transactions.

“This aspect is particularly intriguing,” Kurita says. “As those who use the bunji realize their role in fostering the circulation of the currency through these messages, this creates a sense of belonging and solidarity within the community.

“I see this practice as reminiscent of the ancient societal tradition of gift-giving, revitalized in the contemporary context. It generates an economy driven by principles distinct from capitalist systems, offering a glimpse into the potential for a new economic paradigm.”

Member businesses of the bunji network include household goods and clothing shops, bookstores, and restaurants such as twin cafes Kurumed Coffee and Kurumido Kissaten — both of whose names reflect the kurumi (walnuts) that feature in their dishes, and both of which maintain a slow-life outlook as seen through their onsite publishing company, whose titles include, “Hurry up and slow down.”

Another participating establishment espousing this philosophy is Cafe Slow, a combination restaurant, shop and art gallery located south of Kokubunji Station. The spacious cafe features organic meals and shelves lined with fair-trade products, and regularly hosts events including local markets and candlelight music performances. Its co-founder is social visionary Keibo Oiwa, whose book “Slow is Beautiful” (1996) touched off a slow-living movement in Japan focused on environmental sustainability, antimilitarism, natural energy generation and the interconnections therein. Along with Tokyo Urban Permaculture’s Kai Sawyer, Oiwa has been influential in the long-running, semi-annual conference known as the Economics of Happiness, through which global leaders of the environmental protection movement unite to call for localization. This involves shifting the focal point for addressing pressing social issues away from the centralized governmental and financial systems, and instead toward small-scale, citizen-led actions — including the implementation of community currencies.

The spacious Cafe Slow in Kokubunji, west Tokyo, accepts community currencies from throughout Japan, in addition to the local “bunji” and its own version, the “namake.”

| KIMBERLY HUGHES

In addition to the bunji, Cafe Slow also accepts regional currencies from throughout Japan, and has its own currency, the “namake,” created using both recycled waste and sustainably harvested tagua nuts from Ecuador. Translated as “lazy” or “sluggish,” namake is in fact the namesake of the Sloth Club, launched in 1999 by Oiwa and like-minded proponents of the movement for peaceful slow living. Cafe Slow’s upcoming 2024 event program includes a lectures series led by Hidetake Enomoto, founder of the Transition Town of Fujino, Kanagawa Prefecture, which lies around 40 kilometers west of Kokubunji and features a local currency as an important component of its network.

Towns in transition

The global Transition movement began in the early 2000s in rural England. It encourages communities to find collaborative solutions to ongoing problems, such as replacing fossil fuel dependence with sustainable energy sources amid the climate crisis. Transition Towns have been established throughout Japan, with Fujino remaining one of the most active.

Surrounded by densely forested mountains, the community officially became part of Midori Ward, Sagamihara, in 2017, although locals continue to refer to it as Fujino. The town has long been on the cutting-edge of environmental pursuits, including permaculture, ecological lifestyles and alternative energy generation.

Enomoto launched Transition Town Fujino in 2008, and the network has gone on to hold workshops to construct solar panels and small-scale energy sources for powering smartphones and other devices. Also playing a key role in the initiative is a community currency program called “yorozuya,” which translates roughly as “general store.” Implemented in 2010, the program has provided an online message board for residents to exchange desired goods and services such as gardening, rideshares or household items. Rather than issuing coins or currency notes, members instead record the number of total “yorozu” credits earned and owed inside a special notebook. The listserv has also proved useful as a local information source during disasters like the Great East Japan Earthquake.

Visualizing invisible value

In the southernmost region of the Japanese archipelago, the island of Miyako, Okinawa Prefecture, is looking 1,000 years into the future. Faced with increasing large-scale tourism threatening the health of its pristine waters, the community has implemented its “eco-island Miyako 2.0” to become an ecologically oriented area. While a similar past program did not achieve the level of desired community involvement, Miyako’s local government implemented a community currency in 2018 together with corporate support that is known as risō tsūka (ideal currency). Its unit is the “myahk” (usually rendered in all caps), which is taken from the island’s name in the local dialect. Notes come in denominations of 1, 5, 10, 20 and 50, and their design depicting the island’s sea and sky earned a Good Design Award in 2019. Featuring the tagline “Ii koto o shitara, chotto ii koto” (“doing something good brings something good in return”), the system’s overarching concept is one of “feelings-based compensation whose value is not found within traditionally utilized money; and which serves as a bridge to connect people at the level of their emotions.”

CO Blue’s library and informational clearinghouse features shelves lined with books reflecting its vision for sustainable and balanced living.

| KIMBERLY HUGHES

Another primary objective was to encourage communication among existing public and private efforts for environmental protection. Myahk are earned by local residents and tourists alike for attending local beach cleanup events or environmental talks; and are then redeemable for discounts, goods and services at local businesses. Member stores do not receive compensation, with the idea being that accepting the notes from others enables them to provide indirect support for environmental protection initiatives that they may not be able to participate in as busy shop owners.

The digital future

Local currencies have also been the focus of several gatherings, including a domestic conference held in Fujino in 2017 featuring representatives of regional currencies from throughout Japan. This was followed by an international conference held in 2019 in Hida-Takayama, Gifu Prefecture, which was selected due to its utilization of both digital and analog local currencies — respectively, the “sarubobo” coin, Japan’s first regional cryptocurrency issued by a local credit union; and the “enepo,” diminutive wooden cards distributed to those participating in tree-thinning initiatives in the area’s abundant surrounding forests.

Kurita notes that local digital currencies resembling payment systems such as PayPay or electronic transportation money are likely to continue spreading in Japan, but he believes that “only those digital local currencies that align with the principles of community and aim toward local economic revitalization will end up thriving.”

He adds that tax requirements could become factors when local currencies are used in transactions similar to the Japanese yen, but notes that specific cases may vary, and that the various detailed regulations make it challenging to parse out the details. Nevertheless, he says, “no outright prohibition on local currencies exists in Japan, where there is rather a supportive stance toward their use.”

Kai Sawyer says the community currency movement is also a way to break individuals free from the capitalist mindset they have been brought up in.

| KIMBERLY HUGHES

Echoing the “Ende no Yuigon” documentary, Sawyer also notes that “in mainstream capitalist societies, we are taught that it is impossible to live without money — and we tend to automatically believe it.

“Shifting from traditional to systems-based thinking enables us to understand that we can thrive simply by using our individual interests and skills to help others, without the need to use money at all. When I use the energy of the sun to roast sweet potatoes in my hand-crafted solar oven, it’s like receiving food directly from the universe; and at the end of the meal, there is no bill to pay.”

Sawyer adds that cooking without needing to use gas or electricity is something people are never taught, as we are instead educated to become consumers.

“At this point in time, capitalism is a religion and money is our god, so we cut down trees to erect buildings in order to bring in profits. But looking back historically, it was once the trees who were seen as gods. The story changes.”