“The clothing factory I saw the day after the disaster was indeed a sea of corpses. Those who died on the battlefield in a war were probably not as miserable as this … A man who seemed to be a sumo wrestler died as if he was fighting in the ring, exerting all his strength against an invisible enemy.” —Yumeji Takehisa, “Tokyo Sainan Gashin”

Around a 10-minute walk from Ryogoku Station in Tokyo’s eastern Sumida Ward is Yokoamicho Park. The neighborhood, known for its sumo stables and Kokugikan Arena, was also home to a military clothing depot and was a vacant lot of around 80,000 square meters when the Great Kanto Earthquake struck on Sept. 1, 1923.

It is also where the largest number of victims of the quake and its subsequent fires perished, as depicted above by acclaimed poet and painter Yumeji Takehisa in “Tokyo Sainan Gashin” (“Illustrated Report of the Tokyo Disaster”).

Records indicate the weather that morning 100 years ago was a mixture of drizzle interspersed by clear, blue skies, after a typhoon-induced rainstorm subsided during the night. It was nevertheless turning into another hot and humid day, and people were preparing for lunch when, at 11:58 a.m., a gigantic convulsion estimated at a magnitude of 7.9 struck off the southern coast of Kanagawa Prefecture, rocking the capital, the neighboring city of Yokohama and beyond.

Homes swayed, roof tiles rained on the ground and electricity poles reeled. Fires soon broke out amid the many collapsed wooden structures — exacerbated, likely, by the fact people would have been using stoves to cook their lunches — and quickly spread to more than 130 locations covering all 15 wards of Tokyo. Plumes of smoke darkened the skyline and, fueled by strong winds from a passing typhoon, the many fires began merging into raging infernos, engulfing entire neighborhoods.

In Sumida, residents called on each other to evacuate to the site of the former military clothing factory, which seemed to be a perfect, open space to seek shelter. They retrieved important belongings and furniture from their homes and hauled the objects over to the field, using them to create makeshift barricades. Now, they could just wait for the fire to burn itself out — or so they hoped.

A few hours and several major aftershocks later, the blaze reached the depot, surrounding the evacuees with a wall of fire that quickly spread to their clothes and possessions. More than 38,000 people were burned alive then and there — accounting for over half of the death toll Tokyo recorded, and a third of the total of 105,385 people who perished.

Today, a memorial hall stands on the spot where this living nightmare took place and the park serves as a kind of ossuary, where the remains of those who died are enshrined. A memorial service is held each year on Sept. 1 to pray for their souls.

The Memorial Hall in Yokoamicho Park

| © JOHAN BROOKS

Established in 1930, Yokoamicho Park is among the diminishing number of locations in Tokyo that preserve the fading memories of a century-old catastrophe. And a lot can happen in 100 years, a period during which the capital underwent a dramatic transformation from a quake-ravaged — and then war-torn — city to a slick, modern metropolis.

These monuments from the past — hidden among glitzy high-rises and down obscure, narrow alleys — are reminders of humanity’s courage, vulnerability and ruthlessness after experiencing a tragedy of unprecedented scale, lessons that continue to resonate in a disaster-prone nation bracing for the next big earthquake.

A second disaster arises

“Black rain clouds hang low in the sky on this tumultuous day, and gray smoke from burning corpses creeps across the vacant lot of the clothing factory, licking its way through the air.” —Yumeji Takehisa, “Tokyo Sainan Gashin”

In one corner of Yokoamicho Park is a memorial museum featuring paintings, photographs, charts and various artifacts pertaining to the quake, as well as the American firebombings that destroyed much of Tokyo toward the end of World War II.

“While most of those who experienced the quake firsthand have passed away, we still receive archival material from their children and grandchildren,” says Yusuke Morita, a researcher at the museum.

Yusuke Morita is a researcher at Yokoamicho Park’s memorial museum.

| © JOHAN BROOKS

The most common, he says, are photographs taken in the aftermath of the disaster, especially those that were banned for showing dead bodies. “We assume that many purchased these photos as a record of the event, hiding them as they were prohibited at the time,” Morita says. “And they have since been discovered by their family members.”

Among the exhibits of the museum are the illustrations and essays by the aforementioned Takehisa, who was among the writers and artists who recorded the devastation of 1923 through their mediums of choice, providing an important lens into understanding how society reacted at the time.

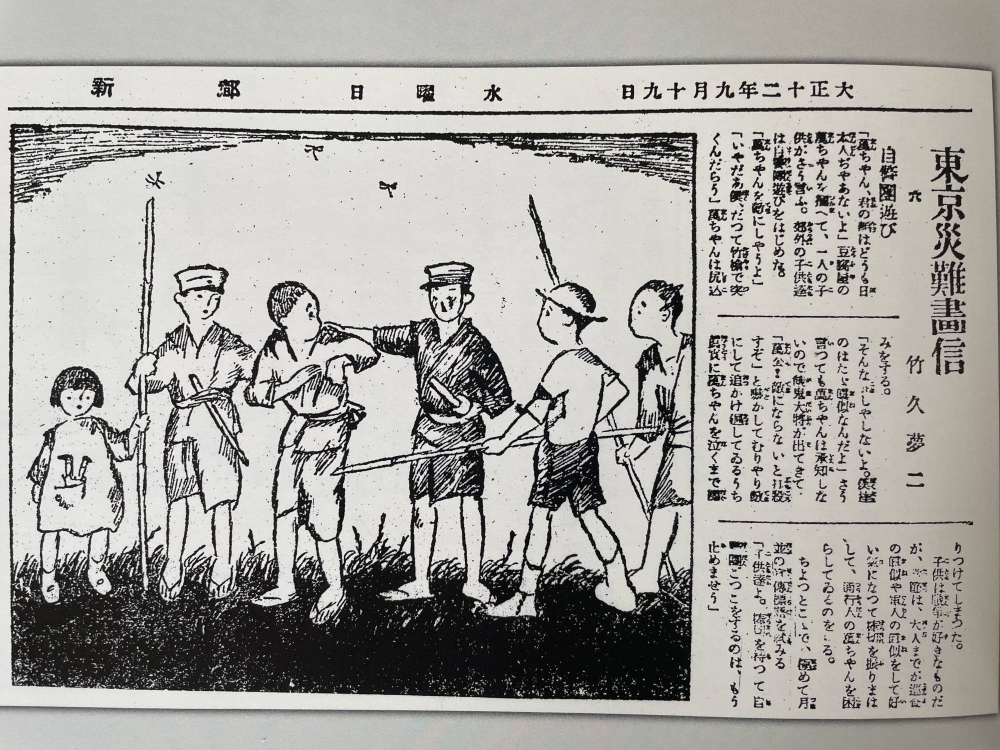

One image in particular reflects the mass hysteria that erupted in the wake of the catastrophe. It shows a group of children bullying a boy for “not looking Japanese.”

“Children, it’s time to stop playing vigilante holding sticks,” Takehisa writes, chidingly.

Artist Yumeji Takehisa depicts a child being bullied for not looking Japanese in “Tokyo Sainan Gashin.”

| ALEX K.T. MARTIN

In the days that followed the Kanto quake, many Koreans, as well as Chinese and Japanese mistaken for being Korean, and Japanese communists, socialists and anarchists were killed by military, police and paramilitary forces. Thirteen years earlier, Japan had annexed the Korean Peninsula.

They were acting on rumors that Koreans were staging riots, setting fires and even poisoning wells. According to a 2008 report compiled by the government’s Central Disaster Management Council, the death toll from the massacre is estimated to account for “one to several percent” of those who perished in the earthquake, which translates to anywhere from around 1,000 to several thousand people.

In Yokoamicho Park stands a stone monument erected in 1973 dedicated specifically to the Korean victims and memorial services are held there each year on the anniversary of the quake. The inscriptions on the black stone slab mention that slightly more than 6,000 Koreans were murdered at the time, a number that remains a source of contention to this day.

A black stone slab stands as a tribute to the reportedly 6,000 Koreans killed in the aftermath of the Great Kanto Earthquake.

| ALEX K.T. MARTIN

After one year in office, Tokyo Gov. Yuriko Koike ceased sending tributes to the ceremony for the Korean victims, breaking a longstanding tradition. Reports say the move came after a Tokyo Metropolitan Assembly member argued that there were differing opinions on how many Koreans actually died. Koike now says she means to express her condolences for “all victims” of the disaster, a stance that has led to criticism from groups organizing the event.

The miracle in Kanda

“For a while after the earthquake, in the midst of the scorched earth of Tokyo, it was like an ‘oasis in the deserts of Africa.’” —Earthquake Prevention Research Committee, 1925

Around 2 kilometers west of the park, near Akihabara Station in Chiyoda Ward, is an antiquated pump station currently undergoing demolition. Built in 1922, the facility is known for playing a crucial role in saving the Kanda Izumicho and neighboring Kanda Sakumacho districts from the ravages of fire, an event known as the “miracle” of the Great Kanto Earthquake.

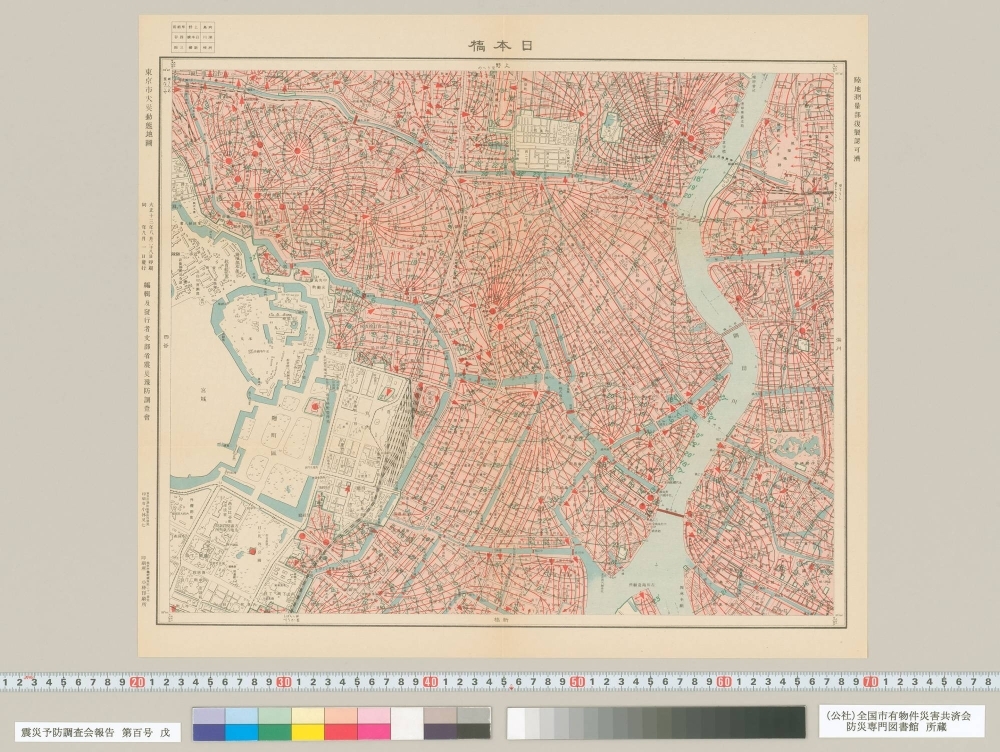

In Tokyo, about 222,000 houses were destroyed from firestorms, while 38.3 square kilometers, or an area larger than Shinjuku and Shibuya wards combined, was burned. A close look at a map of the fire of the city from 1923, however, shows a small square block just north of the Kanda River that isn’t painted in red, indicating it was spared from the blaze.

A map of the burned areas of Tokyo shows a square of white where the “miracle” of Kanda took place.

| DISASTER MANAGEMENT LIBRARY

Historians say the area escaped the spread of fire not only because of the desperate firefighting efforts of its residents, but also because of a combination of favorable conditions: The neighborhoods faced the Akihabara Freight Station to the west and the Kanda River to the south, while being surrounded by noncombustible buildings to the north and east. Finally, there was the pump station completed the year before the quake, designed to deliver wastewater from the locale and transfer it to the Mikawashima Water Reclamation Center in Arakawa Ward.

The old water pump site that was used in saving communities from fire in 1923 has been torn down.

| © JOHAN BROOKS

Soon after the initial jolt, residents began attempting to put ensuing fires out with water bucket brigades while sending children, women and the elderly to evacuate in Ueno Park, around 1.5 kilometers north. “There were also gasoline pumps for firefighting in the area,” says Ko Hamaguchi, an official of Chiyoda Ward’s cultural promotion division. One pump was owned by the Mitsui Memorial Hospital, and the other was a pre-delivery product stored at Teikoku Pompu-sha (Imperial Pumps), a local pump manufacturer.

The gasoline pump from Mitsui Memorial worked around the hospital to protect parts of the town, while Teikoku’s pump was mobilized on the afternoon of the second day, connecting to Kanda Izumicho’s pump station and “becoming the mainstay of the firefighting effort until the end, using gasoline collected by the residents,” Hamaguchi says.

For a century, the two-story brick pump station has stood as a concrete witness to one of the city’s biggest disasters. It had been active until six years ago, when its demolition was ultimately decided. When it goes, so too will one more monument to the past, one that was instrumental in saving lives. In its place? A possible solution to one of Japan’s more modern challenges: a ward-sponsored child care support facility.

On burning pond

“The pond at the Yoshiwara yūkaku was a picture of hell that only those who saw it would believe. Imagine tens and hundreds of men and women boiled in a cauldron of mud. Muddy red cloth was strewn all up and down the banks, for most of the corpses were those of courtesans.” —Yasunari Kawabata’s 1929 essay, “Ryunosuke Akutagawa and Yoshiwara.”

While the pump station and many other remnants of the quake are disappearing, some have been preserved thanks to the efforts of concerned individuals.

Around a 45-minute walk north from Akihabara, past Ueno Park and near Asakusa, is a small, colorful shrine with a tall Kannon, or goddess of mercy, standing above an altar of rocks. In one corner is a tiny pond that is currently being refurbished. This is the Yoshiwara Benzaiten Shrine, a sister shrine to Yoshiwara Shrine, which is located only 100 meters north.

The Kannon statue that stands by the pond at Yoshiwara Benzaiten Shrine where around 500 people died, many of them sex workers.

| © JOHAN BROOKS

“Look carefully at the decorations — they’re mostly handcrafted or painted by myself and a few old friends using spare material and things purchased from ¥100 shops,” says Tatsuo Yoshiwara, an 80-year-old resident of the neighborhood who serves as head of parishioner organizations for both the Yoshiwara and Benzaiten shrines.

Yoshiwara once thrived as Tokyo’s largest red-light district, its history dating back to 1617 when the Tokugawa Shogunate granted permission to create a yūkaku (licensed pleasure quarters) in Nihonbashi in an effort to isolate prostitution to one area of the city. However, the Great Fire of Meireki in 1657 burned down most of Edo (present-day Tokyo) and the pleasure quarters were moved to an area near Asakusa.

Tatsuo Yoshiwara, 80, stands in front of the Kannon statue at Yoshiwara Benzaiten Shrine in Tokyo.

| © JOHAN BROOKS

The place not only functioned as a red-light district, but was a cultural and social hub for patrons who often came from the elite upper class. It was also prone to fire, and strewn with a history of tragedy. Many of the women who found themselves in Yoshiwara were sold into that life, some bought by handlers in poorer regions suffering from calamities such as drought and typhoons.

In the aftermath of the Great Kanto Earthquake, around 500 people trapped in the fire died in the pond, including these women, as depicted by renowned author Yasunari Kawabata in an essay he wrote about the quake and his friend, the legendary novelist Ryunosuke Akutagawa. Every year, a memorial service is held at the shrine on Sept. 1.

The pond back then was much larger and deeper than the small puddle on the premises today. And while Yoshiwara no longer exists as an actual address, the area hasn’t shaken its racy reputation and is now known for its “soapland” brothels.

“Yoshiwara used to be the center of Edo’s culture,” says Yoshiwara, whose name happens to be identical to the neighborhood he lives in. “But in recent years we’ve been associated with soaplands and the yakuza, and that’s having a negative effect on land prices.”

Moved by the gloominess of Yoshiwara Benzaiten Shrine, Tatsuo Yoshiwara picked up some tools and got to work on sprucing it up.

| © JOHAN BROOKS

Yoshiwara’s family used to operate an old-school izakaya pub in the area, on the same property where his office is located now. After college, he opened a ramen shop, then ventured into various businesses including a teppanyaki restaurant, real estate and an underwear shop, all in the same neighborhood.

Around a decade ago, when he was the head of the neighborhood association, Yoshiwara embarked on a project to revitalize both the Yoshiwara and Benzaiten shrines. “They were dark and gloomy, and no one paid much attention to them,” he says. “So I decided to clean these places up by cutting down shrubs and using colorful paints and lanterns to brighten up the atmosphere.”

Today, many tourists visit the Benzaiten Shrine, drawn to its history and significance as a memorial to the many nameless prostitutes who were killed during the quake. Yoshiwara has been asking for donations to fix up the pond, whose concrete shell has been leaking water and is in need of repair. “I want to build a waterfall, too, and have koi swimming in the pond,” he says.

“I’ve lived all my life in Yoshiwara,” he says, while offering his prayers to the Kannon statue. “This is my way of giving back to my neighborhood.”

The importance of memory

“Unlike wars, giant earthquake disasters are not the result of man’s inevitable actions. They are merely the result of the earth moving, causing fires and deaths. For this reason, the impact of the earthquake on us writers is not so deep-rooted.” —from Ryunosuke Akutagawa’s essay, “The Impact of the Earthquake on Literature and Art”

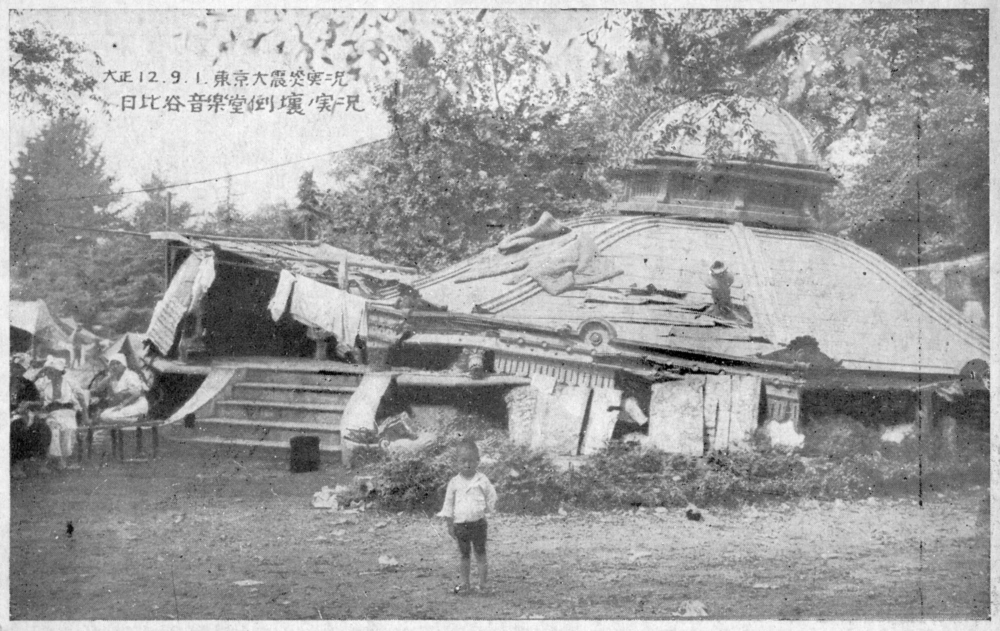

Following the quake, the urban infrastructure of Tokyo was reconstructed under a plan led by Mayor Shinpei Goto. New provisions were added to building laws, making quake-resistant design mandatory for structures in large cities.

A child stands outside of a demolished Hibiya Music Hall.

| PUBLIC DOMAIN

While officials were bolstering roads and architecture, though, it was Japanese society that had become somewhat shakier. The country underwent a time of unprecedented turbulence in the years that followed the Great Kanto Earthquake, transitioning from a period of liberalism known as Taisho Democracy (1912-26) to an era of nationalism and militarism.

There were no shortages of major disasters, including the Sanriku Earthquake of 1933 and the Muroto typhoon of 1934. Meanwhile, the March 15 Incident in 1928 saw crackdowns on socialists and communists, and in 1931 Japan invaded Manchuria following the Mukden Incident, leading to the establishment of the puppet state of Manchukuo the following year.

That same year, Prime Minister Tsuyoshi Inukai was assassinated by a group of naval officers in what is now known as the May 15 Incident, an event seen as fueling the rising clout of the Japanese military and considered an indirect precursor to the Feb. 26 Incident, an attempted coup d’etat in 1936 by a group of Japanese Imperial Army officers. And following the start of the Second Sino-Japanese War in 1937, Japan entered World War II in 1941 with a surprise attack on Pearl Harbor.

By the war’s end, Tokyo was again reduced to ashes.

“There is a noticeable lack of critical research on the more questionable aspects of the reconstruction process following the 1923 quake, perhaps because of Japan’s rapid march toward militarism and, eventually, war,” says Akira Ide, a professor at Kanazawa University in Ishikawa Prefecture and arguably Japan’s foremost expert on dark tourism, or tourism involving traveling to locations historically associated with death and tragedy.

Prince Regent Hirohito, who would later be known as Emperor Showa, surveys the damage in Yokohama.

| PUBLIC DOMAIN

“I tend to think Japan’s overseas expansion was partly to compensate for the massive economic loss from the earthquake,” he says. Damages were estimated at ¥5.275 billion, or a third of the nation’s nominal GDP at the time. “There are other experts who say bureaucracy tends to be centralized during periods of reconstruction, giving rise to nationalism, all theories that deserve more research.”

Ide has visited sites in Tokyo and elsewhere connected to the 1923 quake, including Yoshiwara, and has written about their relevance. “The quake wasn’t an isolated event, and should be discussed as part of a sequence of events that shaped Japan’s modern history,” he says.

A man offers prayers at Yokoamicho Park’s Memorial Hall. Around 38,000 people died at the site after the surrounding inferno became unbearable.

| © JOHAN BROOKS

As memorial services marking the 100th anniversary of the disaster take place across Tokyo and beyond, understanding the socioeconomic and geopolitical consequences of the Kanto quake offers important insights into what could happen when the next big one strikes.

Physicist and author Torahiko Terada was at a cafe in Ueno, chatting with a friend when the temblor struck a century ago. He walked around the city to document the tragedy and eventually helped create the University of Tokyo’s esteemed Earthquake Research Institute.

He is said to have left this famous aphorism: “Natural disasters occur when we forget about them.”